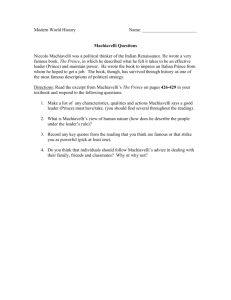

Hobbes vs. Locke READ THE FOLLOWING COMPARISON PAPERS AND DISCUSS THE FOLLOWING 1. Choose a country whose government operates in theory for each of the listed philosophers. 2. Which philosopher is more closely associated with the system of American Government. 3. Identify at least 2 beliefs from each of the philosophers that identifies with an action or decision made by the United States government. 4. Which philosopher more aligns with your belief system, and why? Hobbes vs. Locke 1.) Absolute Monarch 1.) Democracy 2.) People are born with rights that they relinquish to the monarch in return for protection. This is known as social contract. 2.) All people are born with certain inalienable rights. They are life, liberty, and the the right to own property. 3.) Believed that people were wicked, 3.) Believed that people were by selfish, and cruel and would act on behalf of nature good and that they could learn their best interests. “Every man for every from their experiences. man”. 4.) Yes, people could be trusted to 4.) No, people could be trusted to govern govern themselves. Locke believed themselves and an absolute monarch that if provided with the right would demand obedience in to maintain information would make good order. decisions. 5.) The purpose of the government was to keep law and order. 5.) The purpose of the government is to protect individual liberties and rights. 6.) Because people had no say in their government, they could do nothing if the monarch were abusive. 6.) The people had the right to revolt against an abusive government. Niccolò Machiavelli Our assessment of politicians is torn between hope and disappointment. On the one hand, we have an idealistic idea that a politician should be an upright hero, a man or woman who can breathe new moral life into the corrupt workings of the state. However, we are also regularly catapulted into cynicism when we realise the number of backroom deals and the extent of the lying that politicians go in for. We seem torn between our idealistic hopes and our pessimistic fears about the evil underbelly of politics. Surprisingly, the very man who gave his name to the word “Machiavellian,” a word so often used to describe the worst political scheming, can help us understand the dangers of this tired dichotomy. Machiavelli’s writings suggest that we should not be surprised if politicians lie and dissemble, but nor should we think them immoral and simply “bad” for doing so. A good politician – in Machiavelli’s remarkable view – isn’t one who is kind, friendly and honest, it is someone – however occasionally dark and sly Hobbes vs. Locke they might be – who knows how to defend, enrich and bring honour to the state. Once we understand this basic requirement, we’ll be less disappointed and clearer about what we want our politicians to be. Machiavelli wrote his most famous work, The Prince (1513), about how to get and keep power and what makes individuals effective leaders. He proposed that the overwhelming responsibility of a good prince is to defend the state from external and internal threats to stable governance. This means he must know how to fight, but more importantly, he must know about reputation and the management of those around him. People should neither think he is soft and easy to disobey, nor should they find him so cruel that he disgusts his society. He should seem unapproachably strict but reasonable. When he turned to the question of whether it was better for a prince to be loved or feared, Machiavelli wrote that while it would theoretically be wonderful for a leader to be both loved and obeyed, he should always err on the side of inspiring terror, for this is what ultimately keeps people in check. Rather than follow this unfortunate Christian example, Machiavelli suggested that a leader would do well to make judicious use of what he called, in a deliciously paradoxical phrase, “criminal virtue.” Machiavelli provided some criteria for what constitutes the right occasion for criminal virtue: it must be necessary for the security of the state, it must be done swiftly (often at night), and it should not be repeated too often, lest a reputation for mindless brutality builds up. Machiavelli gave the example of his contemporary Cesare Borgia, whom he much admired as a leader – though he might not have wanted to be his friend. When Cesare conquered the city of Cesena, he ordered one of his mercenaries, Remirro de Orco, to bring order to the region, which Remirro did through swift and brutal ways. Men were beheaded in front of their wives and children, property was seized, traitors were castrated. Cesare then turned on de Orco himself and had him sliced in half and placed in the public square, just to remind the townspeople who the true boss was. But then, as Machiavelli approvingly noted, that was enough bloodshed. Cesare moved on to cut taxes, imported some cheap grain, built a theatre and organised a series of beautiful festivals to keep people from dwelling on unfortunate memories.