Dante's Divine Comedy: Life, Context, and Themes

advertisement

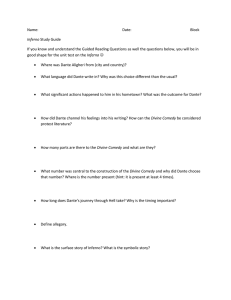

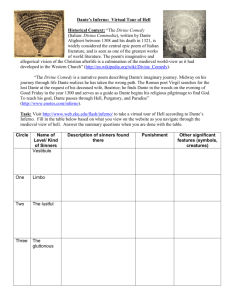

Aligheri Dante (1265-1321) Historical Context Dante Alighieri was born in 1265 in Florence, Italy, to a family of moderate wealth that had a history of involvement in the complex Florentine political scene. Around 1285, Dante married a woman chosen for him by his family, although he remained in love with another woman—Beatrice, whose true historical identity remains a mystery—and continued to yearn for her after her sudden death in 1290. Three years later, he published Vita Nuova (The New Life), which describes his tragic love for Beatrice. Around the time of Beatrice’s death, Dante began a serious study of philosophy and intensified his political involvement in Florence. He held a number of significant public offices at a time of great political unrest in Italy, and, in 1302, he was exiled for life by the leaders of the Black Guelphs, the political faction in power at the time. All of Dante’s work on The Comedy (later called The Divine Comedy, and consisting of three books: Inferno, Purgatorio, and Paradiso) was done after his exile. In Northern Italy's political struggle between Guelphs and Ghibellines, Dante was part of the Guelphs, who in general favored the Papacy over the Holy Roman Emperor. Florence's Guelphs split into factions around 1300: the White Guelphs, who opposed secular rule by Pope Boniface VIII and who wished to preserve Florence's independence, and the Black Guelphs, who favored the Pope's control of Florence. Dante was among the White Guelphs who were exiled in 1302 by the Lord-Mayor Cante de' Gabrielli di Gubbio, after troops under Charles of Valois entered the city, at the request of Boniface and in alliance with the Blacks. The Pope said if he had returned he would be burned at the stake. This exile, which lasted the rest of Dante's life, shows its influence in many parts of the Comedy, from prophecies of Dante's exile to Dante's views of politics to the eternal damnation of some of his opponents. He completed Inferno, which depicts an allegorical journey through Hell, around 1314. Dante roamed from court to court in Italy, writing and occasionally lecturing, until his death from a sudden illness in 1321 His wife meanwhile maintained his home and family back in his beloved Florence. The Big Questions What is man? Why does he act as he does? What is Good and what is Evil? When it so often looks like "Good guys finish last," why should anyone be good? The whole world, ultimately, has meaning, reason, and order. The source of the meaning, reason, and order is God's Divine Plan. The Divine Order is both knowable and achievable. The Construction of the Cathedral The Divine Comedy is composed of over 14,000 lines that are divided into three (3) canticas (Ital. pl. cantiche) — Inferno (Hell), Purgatorio (Purgatory), and Paradiso (Paradise) — each consisting of 33 cantos (Ital. pl. canti). An initial canto serves as an introduction to the poem and is generally not considered to be part of the first cantica, bringing the total number of cantos to 100. The number 3 is prominent in the work, represented here by the length of each cantica. The verse scheme used, terza rima, is hendecasyllabic (lines of eleven syllables), with the lines composing tercets according to the rhyme scheme aba, bcb, cdc, ded, . Albert Ritter sketched the Comedy's geography from Dante's Cantos: Hell's entrance is near Florence with the circles descending to Earth's centre; sketch 5 reflects Canto 34's inversion as Dante passes down, and thereby up to Mount Purgatory's shores in the southern hemisphere, where he passes to the first sphere of Heaven at the top The poem is written in the first person, and tells of Dante's journey through the three realms of the dead, lasting during the Easter Triduum in the spring of 1300. The Roman poet Virgil guides him through Hell and Purgatory; Beatrice, Dante's ideal woman, guides him through Heaven. Beatrice was a Florentine woman whom he had met in childhood and admired from afar in the mode of the then-fashionable courtly love tradition which is highlighted in Dante's earlier work La Vita Nuova. In Hell and Purgatory, Dante shares in the sin and the penitence respectively. The last word in each of the three parts of the Divine Comedy is "stars." Bartokomeo c. 1420 Sandro Botticelli Barry Moser - c. 1980: Major themes The Perfection of God’s Justice – Dante creates an imaginative correspondence between a soul’s sin on Earth and the punishment he or she receives in Hell. The Sullen choke on mud, the Wrathful attack one another, the Gluttonous are forced to eat excrement, and so on. This simple idea provides many of Inferno’s moments of spectacular imagery and symbolic power, but also serves to illuminate one of Dante’s major themes: the perfection of God’s justice. The inscription over the gates of Hell in Canto III explicitly states that God was moved to create Hell by justice (III.7). Hell exists to punish sin, and the suitability of Hell’s specific punishments testify to the divine perfection that all sin violates. Evil as the Contradiction of God’s Will – In many ways, Dante’s Inferno can be seen as a kind of imaginative taxonomy of human evil, the various types of which Dante classifies, isolates, explores, and judges. At times we may question its organizing principle, wondering why, for example, a sin punished in the Eighth Circle of Hell, such as accepting a bribe, should be considered worse than a sin punished in the Sixth Circle of Hell, such as murder. To understand this organization, one must realize that Dante’s narration follows strict doctrinal Christian values. His moral system prioritizes not human happiness or harmony on Earth but rather God’s will in Heaven. Dante thus considers violence less evil than fraud: of these two sins, fraud constitutes the greater opposition to God’s will. Storytelling as a Way to Achieve Immortality – Dante places much emphasis in his poem on the notion of immortality through storytelling, everlasting life through legend and literary legacy. Several shades ask the character Dante to recall their names and stories on Earth upon his return. They hope, perhaps, that the retelling of their stories will allow them to live in people’s memories. – Yet, in retelling the sinners’ stories, the poet Dante may be acting less in consideration of the sinners’ immortality than of his own. Sites Cited “Divine Comedy.” Wikipedia. 1 Dec. 2008 http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Divine_C omedy Gardner, Patrick and Brian Phillips. SparkNote on Inferno. 29 Nov. 2007 http://www.sparknotes.com/poetry/inferno/ The World of Dante. Institute for Advanced Technologies in the Humanities http://www.worldofdante.org/