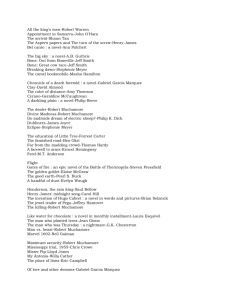

Grace Taylor April Shoemaker English 102 4 Febuary 2019 The Unexceptional Reject “A Very Old Man with Enormous Wings” by Gabriel José de la Concordia García Márquez is a short story about an elderly man with “huge buzzard wings” who is trapped in a small seaside home and courtyard for several years (Márquez 317). The respected neighbor woman “who knew everything about life and death” identifies the winged man as an angel, a definition that most members of the community and the anonymous narrator initially accept (Márquez 317). Initially, the observers of the man are inclined to make him “the mayor of the world” or “promoted to the rank of five-star general to win all wars” (Márquez 318). After a short period of time, the town realizes the old man is “much too human” and dismisses the idea that the man’s wings are notably abnormal (Márquez 318). Márquez created his story to expose humanity’s cruel negligence to outsiders, and he defined the old man’s otherness, not by his winged state, but by his inability to communicate, uselessness to the town, and morbidly mortal state. A major barrier between the old man’s connection with the people of the town is his “incomprehensible dialect” (Márquez 317). The old man does not know and is too senile to learn their language. In addition, he did not understand Father Gonzaga’s Latin. Márquez utilizes a third-person narrator that peers into the minds of the townspeople but never the old man. ”The story, in fact, vacillates between the perspective of the omniscient narrator and that of the villagers, individually and collectively” (Slomski). The readers are only left with a surface level description of the man and have no insight into his history, internal dialog, or true state of being. He is intentionally as much of an enigma to the reader as he is to the rest of the characters and is more difficult to empathize with. Márquez interrupts his narrative with the story of the spider-woman who traveled with the carnival. “What was most heartrending, however, was not her outlandish shape but the sincere affliction with which she recounted the details of her misfortune” (Márquez 320). That interaction sparks a sympathy in the townspeople that was nonexistent when dealing with the more humanlike old man. The narrator and community continue to use the term angel out of convenience, and every character who comes into contact with the old man rejects their initial preconceptions and realizes the old man is a much more depressing and mangy creature. Ronald E. McFarland, a University of Idaho professor, wrongly asserts that “The community, however, quickly accepts... that the old man is an angel… nor does the community alter its attitude toward the identity of the old man...” Each character, however, becomes disillusioned easily. The few mystical abilities that the old man possesses are, like the old man’s appearance, comically disappointing. “Besides, the few miracles attributed to the angel showed a certain mental disorder, like the blind man who didn’t recover his sight but grew three new teeth…” (Márquez 320). His reputation is completely ruined when he produces no great revelation. The cursed spider-woman produces a clear moral (listen to your parents). “The angel, however, does not work like that. He is irreducible and irascible and useless. He may be allegorized, but the allegorization is not he” (Janes). After the spider-woman “crushed” the public’s interest in the old man, he is completely useless to Elisenda and Pelayo, his kidnappers (Márquez 320). Ironically, they “extend him the charity of letting him sleep in the shed,” while they would shew him out of their home and ignore the deteriorating state of his chicken coop (Márquez 321). The old man is essentially treated like an old dog, because, unlike the child, the old man has no potential and no reason for investment. The old man is shunned from the home and mind of Elisenda, the woman who orchestrated his public humiliation and torment. She benefits the most from the character that she cannot stand and describes as “an annoyance in her life” (Márquez 322). His decrepit and senile state made Elisenda “exasperated and unhinged” (Márquez 321). His dying appearance only drew out sympathy from Pelayo, which was revealed to be more of a fear of supernatural death. What truly disturbs Elisenda and the villagers, however, are the most natural parts about him and the same qualities they must face in their old age. At the beginning of the story, the old man is first described as having a “pitiful condition of a drenched great-grandfather” that removes any “grandeur” or social importance (Márquez 317). Elisenda and Pelayo view his exceptional age and lifespan as shameful and inelegant. Even Father Gonzaga was “cured forever of his insomnia” (Márquez 320) when the “huge decrepit hen” (Márquez 318) was finally out of his and the public’s eye. The old man’s human smell, “whistling” heart, and “foggy” “antiquarian eyes” (Márquez 321) that do not “measure up to the proud dignity of angels” (Márquez 318) kindles a fear in the onlookers and readers alike that they also never will. Márquez’s short story is a parable about the preventable suffering of the alienated. His titular character, the old man, is lifted, stretched, and dropped from a godlike status to that of an animal. His wings have little relevance in his poor treatment, as they are quickly dismissed by halfway through the story. The rejection of his humanity and sympathy stems from a lack of a common language and his senile, incapable state that is the grotesque fate of Father Gonzaga, Pelayo, Elisinda, the neighbor woman, and even the child. Works Cited Janes, Regina. "A Very Old Man with Enormous Wings: Overview." Reference Guide to Short Fiction, edited by Noelle Watson, St. James Press, 1994. Literature Resource Center, Accessed 3 Feb. 2019. Márquez, Gabriel García. “A Very Old Man with Enormous Wings.” Perrine’s Literature: Structure, Sound & Sense, edited by Greg Johnson and Thomas R. Arp, Cengage Learning, 2015, pp. 317-322. McFarland, Ronald E. "Community and Interpretive Communities in Stories." Short Story Criticism, edited by Thomas J. Schoenberg and Lawrence J. Trudeau, vol. 83, Gale, 2005. Accessed 3 Feb. 2019. Originally published in Studies in Short Fiction, vol. 29, no. 4, Fall 1992, pp. 551-560. Slomski, Genevieve. “‘A Very Old Man with Enormous Wings.’” Masterplots II: Short Story Series, Revised Edition, Salem Press, 1986. Literary Reference Center Plus, Accessed 3 Feb. 2019.