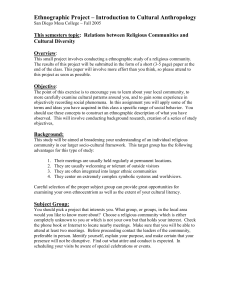

bs_bs_banner New Ethnographic Film in the New China MARIS BOYD GILLETTE Over the past two decades, a new ethnographic cinema of China has taken shape, one element of an explosion of documentaries produced about the People’s Republic. In this volume, five China ethnographers discuss making ethnographic films in China, thus addressing in part the need, long noted in anthropology, for filmmakers to write about production and postproduction of ethnographic films. In this introduction, I sketch a history of ethnographic films about China and reflect on these five new ethnographic films in light of past practices, the theoretical literature on ethnographic cinema, and the ethnography of China. [anthropology, China, ethnographic cinema, ethnography, filmmaking, history, research methods] Introduction I n the last couple of decades, viewers have witnessed an explosion of documentaries about the People’s Republic of China (PRC). Chinese filmmakers are producing the bulk of this work, with filmmaker Wu Wenguang widely recognized as a founding figure of the new Chinese documentary movement (Berry et al. 2010; Zhang 2004b; see also Sniadecki, Zito this volume). Many of these films explore the effects of marketization and globalization in China, what Angela Zito has called “the underbelly of the Chinese economic miracle” (Zito this volume).1 Noncitizen filmmakers are also contributing to this corpus, exploring social issues such as AIDS (Yang 2006), the Three Gorges Dams (Chang 2007), and labor migration (Peled 2005). A new ethnographic cinema of China has taken shape during this same period. The mainstream media for the anthropology of China remains the written word, yet inside and outside the PRC, ethnographers have turned to film to convey “a vivid sense of what it feels like to be someone else,” as the well-known American film scholar Bill Nichols puts it (Nichols 2010:8). In the PRC, Yunnan University is widely recognized for producing ethnographer–filmmakers, a development begun through a 1994 collaboration with Germany’s Goettingen Institute for Scientific Film (Chen and Lei 2009:103–104; Zhang 2004b:n. 8; see also Blumenfield 2010; Chio this volume). Outside China, a new generation of ethnographers is committed to incorporating Visual Anthropology Review, Vol. 30, Issue 1, pp. 1–10, ISSN 1058-7187, online ISSN 1548-7458. film into their research from its inception, while some more senior scholars are experimenting with the medium after years, even decades, of field research and print publication. While the number of ethnographic films is increasing, there are still few texts written about the process of making ethnographic films, despite years of complaints from anthropologists who study and teach ethnographic films. For example, Peter Loizos concludes his 1993 book Innovation in Ethnographic Film with a call for ethnographic filmmakers to produce more study guides and information about filmmaking processes, to facilitate the use of ethnographic film in academic settings (Loizos 1993:191). Karl Heider, whose 1976 book Ethnographic Film was recently published in a second edition, contends that ethnographic films, while “self-explanatory for casual use,” require an accompanying ethnographic text for deeper use (Heider 2006:7). He observes that we do not know who filmmakers intend as their audience, or why they make the shooting and editing decisions they do, and argues that ethnographic filmmakers have an obligation to write about how they “distort” reality and what their aims are (Heider 2006:100, 107). More recently, Carol Hermer has encouraged ethnographic filmmakers to write about their specific purposes and methods of production. She notes that while there is “much excellent theoretical writing on all aspects of ethnographic film and its communication,” by and large the audience of any particular ethnographic film must “make an educated guess as to what has taken place during © 2014 by the American Anthropological Association. DOI: 10.1111/var.12026. 2 VISUAL ANTHROPOLOGY REVIEW Volume 30 Number 1 Spring 2014 production and what the filmmaker’s viewpoint is” (Hermer 2009:122). In this special issue of Visual Anthropology Review, ethnographers of China who decided to produce one or more ethnographic films about the contemporary People’s Republic, rather than depend solely on the power of the word, discuss their filmmaking processes. While far from comprehensive, the volume helps address the need for ethnographer–filmmakers to discuss their intentions, production and postproduction decisions, conceptual frameworks, and film models. Just as important to the readers of Visual Anthropology Review, the authors also illuminate key aspects of making ethnographic films in China. Each ethnographer–filmmaker encountered people, experiences, and sociocultural processes in contemporary China that warranted public attention and cried out for the filmic medium, but which he or she thought existing scholarship and media represented inadequately. The volume sheds light on contemporary ethnographic cinema as a conceptual enterprise, research method, set of social relationships, genre of communication, and contribution to the historical archive. The articles, and the films they are about, present fresh approaches to the ethnographic cinema of China, showing recent developments in a history that began 25 years before the People’s Republic was founded. A Notional History of Ethnographic Film in China Documentary film arrived in (late imperial) China less than eight months after the Lumiere brothers showed their first shorts in Paris (Zhang 2004a:14, 114–115). In August 1896, short documentary films were shown in Shanghai, and a Japanese merchant showed ten documentary shorts with Edison’s kinetoscope in a Taiwan coastal town (officially part of Japan at the time, as the Qing government ceded Taiwan to the Japanese after the first Sino-Japanese war in 1894). The first Chinesemade documentary, about Peking Opera, was produced in 1905 (Chen and Lei 2009:72–73). Arguably, the American sociologist and long-term China resident Sidney Gamble made the first ethnographic film about China 20 years later. A 1989 remake of his A Pilgrimage to Miaofeng Shan, originally shot between 1924 and 1927, is readily available online through the Duke University Library and YouTube (http://library .duke.edu/digitalcollections/gamble/documentary/).2 In 1933, Chinese ethnologists Ling Chunsheng, Rui Yifu, and Yang Shiheng made a series of films about the Miao, Yao, and other peoples in southwest Hunan (Chen and Lei 2009:76). Four years later, Lingnan University professor Yang Chengzhi collaborated with filmmaker Kuang Guangliu to make films about Hainan islanders as part of a large-scale ethnography (Chen and Lei 2009:77). These were the last ethnographic films made until after the founding of the People’s Republic. After 1949, the Chinese Communist Party claimed for itself the task of creating a New China (the phrase itself is usually attributed to Mao Zedong), and quickly turned to cinema as an important tool. The government nationalized the film industry in 1952 and established the Central Newsreels and Documentary Studio early in 1953 (Chu 2007:53; Zhang 2004a:192, 200). Political ideology was the framework for all filmmaking: documentary, feature, and ethnographic. In the period before 1961, PRC films were to emphasize the contrast between the bad Old Society and the virtues of the New China (Chu 2007:158–159). This message came through loud and clear to audiences, as John Weakland’s 1966 article in American Anthropologist on “Themes in Chinese Communist Films” demonstrates (Weakland 1966:479–480). As Weakland notes, the bad old China was characterized by feudalistic families, corrupt officials, and oppressed women, whereas the good New China liberated women and youth and ushered in an era of social cooperation. However, sexual relations were something that one should be cautious about in the New China (Weakland 1966:481). In 1955, Mao Zedong ordered production of what we usually consider the first ethnographic films produced in the People’s Republic (Chu 2007:65; Zhang 2004b:n. 8). These were films about ethnic minorities at the time of Liberation, intended as a kind of salvage Maris Boyd Gillette is an anthropologist and filmmaker currently living in Uppsala, Sweden. She has written several articles about the porcelain industry in Jingdezhen, China. Broken Pots Broken Dreams, about Jingdezhen’s ceramic workers, is her first solo documentary. Gillette has worked on a number of digital video community history projects in Philadelphia, including Precious Places and Muslim Voices of Philadelphia. She is writing a book about Jingdezhen’s porcelain production from 1004, when its wares first caught the attention of the imperial court, through centuries of government sponsorship, to the present moment of private enterprise. She has also written extensively about Hui Muslims in Xi’an. Gillette is a professor of anthropology at Haverford College and the European Institutes for Advanced Studies Fellow at the Swedish Collegium for Advanced Study. New Ethnographic Film in the New China ethnography of past societies (Du and Yang 1989:21–26). Fei Xiaotong, well known in Chinese circles as a student of Bronislaw Malinowski and a pioneer of ethnography in China, administered the project. Researchers and filmmakers scripted these ethnic classification or Minzu Shibie films (dating from 1957 to 1966) and asked locals to participate—or act—in them. Even so, the anthropologists who worked on the films regard them as realist documentation, with “no fabrications” or “subjective evaluations.” Their goal was to capture a vanishing world before it completely disappeared, but also to present a world that conformed to Marxist notions of social evolution. The films were not intended for public viewing and little information is available about who actually saw them at the time of their completion (Chu 2007:155; Du and Yang 1989). We do know, however, that in 1961, after films about the Li, Wa, Ewenki, Kucong, Dulong, Yi, and Tibetans were made, the Ministry of Culture hosted a meeting where filmmakers and anthropologists discussed the relationship between political ideology and historical actuality, the role of reenactments, and the emphases of the films (Chu 2007:156). From 1949 into the early 1980s, almost all ethnographers who were not PRC citizens were prohibited from doing field research in mainland China. Yet many were fascinated with the systems of social relationships, ritual practices, and economic organization characteristic of what was often called “traditional” China. During these years, ethnography based in Hong Kong (urban areas and the rural New Territories) and Taiwan dominated the anthropology of China. A few ethnographers, most notably Gary Seaman, got behind the camera to capture the lifeways of small-scale communities and the colorful, even exotic popular religious practices found in Hong Kong and Taiwan. Some ethnographers collaborated with filmmakers on ethnographic films, including founders in the field of China anthropology such as Margery Topley, Barbara Ward, Bernard Gallin, C. Fred Blake, Hugh Baker, and Norma Diamond. The 1960s and 1970s saw production of 25 or more ethnographic films about China, based in Hong Kong and Taiwan. These films conveyed the sensory dimensions of local experience more than contemporary anthropological books and articles, which mostly focused on social structure. Speaking generally, films such as Hungry Ghosts (Kehl 1970), Ways of the Middle Kingdom (Gibb 1971), Dragons on the Sea (Gibb 1973), Gary Seaman’s (1974) Chinese Popular Religion Series, the Taiwan Series (Chen and Tsai 1974), the China Coast Series (Miller 1974), and Da Jiu (Gibb 1977) took collective practices and groups as the main unit of GILLETTE 3 inquiry. They were realist and didactic in orientation. Many had voice-over narrators and dubbed translations over participants’ voices. Several focused on popular religion and ritual, and those that looked at economics usually explored local modes of production without considering their integration into broader economic systems. These films generally eschewed explicit discussion of politics. For the most part, reviewers appreciated these films as shedding light on the lives of ordinary Chinese and providing rich visual material for academic and public audiences. For example, the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) praised Hugh Gibb’s Dragons on the Sea, which drew heavily on Barbara Ward’s ethnographic research on boat people between 1950 and 1973, for “imaginatively capturing the details of their everyday doings and colourful traditional festivities” (Observer 1973). Anthropologist Stephan Feuchtwang agreed that the film was “entertaining, well-shot, and informative,” but also complained about the “profusion of detail” and “the frustration of being taken on a tour rather than into a deepening insight” (Feuchtwang 1975). Feuchtwang similarly critiqued Gibb’s Da Jiu as a “patch-work” of too many subjects (Feuchtwang 1977:6). He noted Gibb’s “banal emphasis on the passing of tradition,” pointing out that Gibb could equally well have discussed the ways that Hong Kong’s colonial government kept traditions like this large-scale ritual alive (7). In this specific ritual, a British colonial official opens the civic portion of the ceremony, but Gibbs did not follow up on this important context. Feuchtwang recommends Gary Seaman’s Chinese Popular Religion Series as a “far superior” treatment of Daoist religious practice. Seaman received high accolades for showing whole rituals in a manner that is “real,” “vivid and revealing,” and “graphic” (Gonzales 1975a, 1975b, 1975c; see also Feuchtwang 1977). Yet at least one anthropological viewer wanted more context, asking why the rituals Seaman filmed took place and how locals reacted. Nancie Gonzales notes that Seaman made a conscious choice to depict only public ritual practices, in an effort to adhere to village norms and produce films that were considered “appropriate.” Still, she writes, “it is difficult to imagine what the function and meaning of these rituals may be for the participants themselves,” and notes the absence of “that ‘personal’ feel,” which interviews with ritual participants would promote (1975c). Anthropological reviewers of the Taiwan Series and China Coast Series also wished for more context (Strauch 1977; Wolf and Wolf 1977). Margery and Arthur Wolf, who reviewed the Taiwan Series for American Anthropologist, thought the films created erroneous understandings among viewers and only 4 VISUAL ANTHROPOLOGY REVIEW Volume 30 Number 1 Spring 2014 recommended the short on wet rice agriculture (Wolf and Wolf 1977). Where Seaman’s work lacked interviews, the Wolfs argue that Chen included too many. Judith Strauch (1977) has stronger praise for the China Coast Series, which she lauds as “visually excellent” and an “interesting and valuable ethnographic picture,” but she notes the absence of an emic point of view, and finds the films occasionally “incoherent” and “dull.” She too wishes for more context. During the 1980s, after Mao Zedong’s death and Deng Xiaoping’s decision to open China and implement a market economy, the scope for ethnography in the PRC gradually increased, for PRC and noncitizen anthropologists alike. Political restrictions influenced what kinds of ethnographies were possible, as all ethnographic projects required government approval and sponsorship by a work unit. Since studies of minority ethnic groups (shaoshu minzu) and rural communities were accepted fields in the Chinese academy, many ethnographers worked with ethnic minorities and/or in rural communities (e.g., Anagnost 1985, 1987; Harrell 1989, 1990, 1992; Schein 1989, 2000; Yan 1992, 1996). This new research took a different direction from that conducted in Hong Kong and Taiwan. Many ethnographers explored questions of social change and government policy, given the state’s dramatic efforts at social engineering. Most of the PRC-made ethnographic films during the 1980s were about ethnic minorities. Many were made by researchers at universities and research institutes in Beijing and Yunnan (Chen and Lei 2009:94–97, 102, 108–109). Documentary film scholar Yingchi Chu characterizes these films as moving away from the “dogmatic formula” of the Maoist period (Chu 2007:161–162). While the state still steered production, filmmakers had more decision-making power, and a “broader spectrum of images” could be shown. In addition, these films had to respond to market forces. Government officials wanted them to promote tourism and economic development in minority areas. Political sensitivities partly explain why many fewer ethnographic films were produced by noncitizen filmmakers during the 1980s and 1990s. The first ethnographic films about the New China by non-Chinese citizens were part of the English Disappearing Worlds series. In 1982 and 1983, filmmaker Leslie Woodhead collaborated with anthropologist Barbara Hazard to make two films in Wuxi (Inside China: Living with the Revolution and Inside China: The Newest Revolution), and André Singer worked with Shirin Akiner to make one on the Kazakhs in Xinjiang (The Kazakhs of China). Their focus was historical, political, and familial. The Wuxi films examine how government policies under Mao and Deng affected family economic opportunities, gender roles, the relationships between generations, and so on. The Kazakh film follows a herding family as they move from plains to higher pastures and prepare for their daughter’s wedding. It shows negotiations between the village’s production team and higherlevel administrative authorities who managed village resources. Alan Jenkins, then a senior lecturer in Geography at Oxford Polytechnic, published a production study of the two Wuxi-based Disappearing Worlds films (with an occasional remark about the Kazakh film) in Anthropology Today (1986). Jenkins describes the extensive negotiations that Granada Television and Chinese officials had before coming to an agreement that Granada could produce two “ethnic” films and one about Han Chinese (Jenkins 1986:7–8). Ultimately, this agreement broke down, and the third film, which was to be sited in Yunnan, was cancelled. For the Han Chinese documentary, Granada’s filmmakers wanted to work in an area where ethnographic work had been done, but there were few PRC-based ethnographies to choose from (8). Ultimately they selected Jiangsu, hoping to work in the village where Fei Xiaotong had done his 1939 study Peasant Life in China. However, Chinese officials would only allow them to work in suburban Wuxi and the crew was not permitted to live on-site (Jenkins 1986:8–10). During filming, Chinese “minders” who “stuck like glue” accompanied the crew, steering them to “a very model family containing a dynamic, photogenic party official” (Jenkins 1986:9). Granada also had to compromise on the issue of anthropological expertise, hiring sociologist Barbara Hazard for her work on state–peasant relations. Hazard had never worked in Wuxi and did not speak the local dialect. Even with these challenges, reviewers lauded the two final Wuxi films as “a dramatic breakthrough in ethnographic filming for a general audience” that featured “ ‘native’ peoples telling their story direct to camera, rather than the then dominant convention of a western presenter telling their story” (Jenkins 1986:12; see also Henley 1985:8–9, 14). A reviewer in the Observer emphasized the “constant sense of recognition, of common humanity” that the films produced, noting that the film crew “travelled to China and found themselves in Coronation Street . . . Mrs. Zhu [c]ould be Hilda Ogden” (Banks-Smith 1983). The Kazakh film was described as “the scoop” of the China trilogy for the insights and unparalleled access it gave into an understudied northwestern minority and minority-majority relations (Feuchtwang 1983). New Ethnographic Film in the New China Anthropologists who reviewed the films still wanted more context, of course, particularly about government policy (Feuchtwang 1983; Watson 1983). The Kazakh film was not “a concerted probing of Kazakh existence in China,” Stephan Feuchtwang wrote: tensions were shown, but not investigated, despite the film crew’s claim that they were not hampered by the presence of government officials (Feuchtwang 1983). Rubie Watson writes that the Wuxi films effectively presented the new materialism brought about by the market reforms, but they did not explain these policies or tell us enough about young people (Watson 1983). She and other reviewers noted that the filmmakers needed to talk about the Communist practice of “speaking bitterness,” where older citizens are asked to describe the hardships of the pre-Communist past (Jenkins 1986:12; Mirsky 1983; Watson 1983). Since audiences are not informed about this speech genre, they are unable to recognize the ways in which the Wuxi interviews were shaped by it. Carma Hinton’s well-known One Village in China Series, most of which came out in 1984, adopted a similar approach to that of the Disappearing Worlds films. The films look at social changes in farming, family, and ritual life and are driven by interviews with locals. Hinton grew up in China and spent time in the north China village where her father, William Hinton, conducted ethnography. The films she made in Long Bow reflect her close relations with villagers and sensitive understanding of local life. In particular, Hinton’s film Small Happiness (1984) is a compelling portrait of changing gender relations and family dynamics in a rural community over a 70- or 80-year period. Small Happiness remains one of the most-used ethnographic films about China of the 20th century. Reviewers of the One Village in China Series commented on the films’ naturalism, observational footage, and the “unparalleled access” made possible by the Hintons’ long relationship with the villagers (Graves 1987; Ikels 1985:741; Kehl 1984). The conversations appear “relaxed,” and villagers displayed a wider range of emotions and viewpoints than audiences had previously seen. Hinton’s commentary provided important contextual information; only the fourth film, All Under Heaven, is critiqued for inadequate historical background (Graves 1987). In general, the films were celebrated for their frankness and the sense of intimacy they created between film subjects and audiences. Hinton went on to make many other films, including one on the Tian’anmen movement in 1989 (The Gate of Heavenly Peace, 1995) and another on the Cultural Revolution of the 1960s and 1970s (Morning Sun, 2003). Among other things, Hinton is recognized for her inter- GILLETTE 5 views, which elicit revealing participant testimony. The later films differ from the One Village in China Series in their overt political focus. They are topic-driven rather than location-driven, and by some standards less ethnographic than the earlier work. Scholars describe increasing numbers of ethnographic films produced in the PRC during the 1990s, particularly after 1993. Hundreds of documentaries about minorities were made, many by independent filmmakers (Chu 2007:180). Many foregrounded participant testimony and tried to speak to the concerns of the film subjects (Chu 2007:181; Zhang 2004b). Both documentary and feature films from the late 1990s and 2000s are characterized as having an “ethnographic sensibility” (Schein 2013; see also Zhang 2004a:281–292, 2004b). They have generated enormous scholarly interest, resulting in numerous articles and edited volumes (e.g., Berry et al. 2010; Blumenfield 2010; Chu 2007; Schein 2013; Zhang 2004a, 2004b; Zito 2013). Looking more narrowly at visual anthropologists, several ethnographic filmmakers are regularly noted for their work. Zhuang Kongshao is recognized for producing a set of films between 1992 and 2004 about cultural heritage, food, ritual, and applied anthropology (Chen and Lei 2009:98–99). Anthropologist Deng Qiyao also made several films during this period, on the Zhuang, Lahu, and other Yunnan minorities. Sun Zhongtian, professor at Northeast Normal University, won an award for the documentaries he made about northeast China minorities for CCTV (Chen and Lei 2009:111–112). Guo Jing is also widely cited for his participatory videos made in collaboration with Tibetans living near and on Mount Kawakarpo (Chu 2007:181–182). Although this sketch focuses on ethnographic films about the New China (or People’s Republic), no discussion of ethnographic cinema from the Chinese world could be complete without mention of anthropologist Hu Tai-li. Hu works exclusively on Taiwan and presents her work as such, rather than suggesting her cinema stands for China as a whole, as did many of the early ethnographic films from Hong Kong and Taiwan. She produced her first film on a large ritual conducted by a Taiwanese aboriginal tribe (Hu 1985), and subsequently has considered many aspects of aboriginal life. Perhaps her best-known film is Voices of Orchid Island (1993), in which she presents three “invasions” of an aboriginal island south of the main island of Taiwan: tourism, medicine, and nuclear waste—with anthropologists subtly indicated as a fourth kind of invader. Voices of Orchid Island eschews narrative voice-over and highlights observational footage. In broad strokes, this notional history sets the stage for the ethnographer–filmmakers of China included in 6 VISUAL ANTHROPOLOGY REVIEW Volume 30 Number 1 Spring 2014 this volume to discuss why and how they made the films they did. The ethnographic filmmakers whose work is featured here faced few political restrictions. They entered a field characterized by a strong movement away from didactic presentations and voice-over narrators, and dominated by naturalistic approaches and film subjects who spoke “in their own voice” (more or less). Representations of minorities had emerged as the privileged subjects of ethnographic films in the New China, with religion and ritual a second theme. These filmmakers were aware of, and in many cases had participated in, ethnographic discussions about social change and state policy in post-Mao China. In their films and articles, they speak to the legacy of China ethnography, ethnographic film on China, and the range of media representations about China that circulate today. Only a fraction of the total number of ethnographer–filmmakers currently working in China could be included in this special issue. Each contributor participated in the film festival and workshop entitled “Forbidden No More: New Ethnographic Film in the New China,” sponsored by Haverford College on February 24–26, 2012. I organized the event in conjunction with an undergraduate class that I teach on the Anthropology of China, inviting ethnographers whose writings and films I used for that course. The class is offered at the intermediate level and does not require language proficiency beyond English. This meant there were many ethnographers publishing and making films in other languages whose work I could not include. My home institution was extraordinarily generous in the resources it devoted to “Forbidden No More,” but even so, limitations of funding and time also constrained participation, particularly for PRC-based ethnographic filmmakers. Fortunately, recent years have seen a spate of publications on documentary filmmaking in China, including some that address ethnographic cinema specifically (e.g., Berry et al. 2010; Chu 2007; Zhang 2004b; Zhuang 2009). We can also look forward to new publications, as emerging and more established scholars (including some represented here) revise and publish dissertations, presentations, and conference papers on the topic. Ethnographic Cinema and Media Worlds Nonfiction film (and to some extent fiction film) has an “indexical stickiness,” as anthropologist and filmmaker Peter Loizos puts it (Loizos 1993:6–9; see also Chu 2007:13–17; Zito 2013). The indexical relationship between nonfiction film and the real gives ethnographic film enormous descriptive potential (Heider 2006:63; Seaman 1977:365). It excels at communicating the concrete, the personal, the individual, and the specific (Loizos 1993:67–68; MacDougall 1998:73–81). As ethnographic filmmaker and author David MacDougall has written, it engages the viewer’s body and emotions and invites the viewer to learn through a kind of direct experience (MacDougall 1998:61–63; see also Sniadecki this volume). Ethnographic film is both detached from and linked to historical reality, albeit in different proportions and (I hope) with different significance than fiction film. Its power relates directly to the filmmaker’s ability to frame and make available the historical world in a way that gives viewers something special. The filmmaker crafts viewers’ experiences, though she does not entirely control them (see Martinez 1992; Moggan 2005). As Bill Nichols (2010:17) writes, viewers cannot escape the filmmaker’s perspective, though they may not agree with it. Nichols (2010:xix) observes, “Film is central to the representation of values and beliefs, customs and practices in modern culture.” Nonfiction film has a special role in this regard, as documentary can challenge the media representations that dominate how most people get access to reality (Nichols 1991:107–109). Loizos (1993:191–192) argues that anthropologists have a special obligation to attend to, think about, and contest how the media represents the people we study. Faye Ginsburg goes a step further, arguing that anthropologists need to situate their work in relation to mass media, study media as a subject of ethnographic inquiry, and recognize media work as a kind of political action (Ginsburg 1994). The ethnographer–filmmakers in this volume all locate their films in relation to texts, documentaries, news reporting, fiction film, photography, and ethnographic cinema. Despite the persuasive force of Ginsburg’s “(mild) polemic,” this is still a significant departure from most ethnographic writing, as ethnographers typically only position their texts in relation to print media, and usually only to academic print. It sets the ethnographer–filmmakers in this volume apart from other ethnographic filmmakers working in China. The articles in this volume reveal how ethical concerns and political advocacy color these ethnographers’ filmmaking projects. The ethnographers represented here are far more explicit about their intentions and agendas than previous generations of ethnographic filmmakers working in China. Chio and Gillette directly relate their films to popular media narratives about China: representations about what is and is not Chinese, what kind of place China is, geopolitical concerns New Ethnographic Film in the New China about China’s influence in the world. Zito discusses her decision to film urban retirees who rarely if ever get the spotlight in documentaries or writings, and whom many Chinese consider unworthy of attention. Dean and Dean describe their efforts to countermand the impression that Daoism is somehow a thing of the past by showcasing the revival, reinvention, and fantastic scale of popular religious practice in contemporary Fujian. Chio, Sniadecki, and Zito reflect on what they, as noncitizen ethnographer–filmmakers, bring to the world of Chinese documentary, and how their films complement and differ from those by PRC-based independent filmmakers. All of the filmmakers felt that the filmic medium enabled knowledge that texts could not and transmitted that knowledge to audiences beyond those who read scholarly writing. The films are not “B roll,” illustrating knowledge dependent on words, oral or written. The sights and sounds give access to sensation, embodied exploration, and emotional identification that are ends in themselves. Sniadecki explicitly rejects linguistic properties in Chaiqian. His focus is sensory: bodies doing (various kinds of) work in a particular place. Chio also directs us to see, feel, and understand working bodies, not only manual labor but also the performances and salesmanship required for success in tourism. Gillette sought to convey working bodies and places while privileging the development of emotional identification between viewers and film participants. Zito not only provides character portraits, both human and nonhuman, but also visually and aurally re-creates the flows and stoppages that punctuate calligraphic practice. Dean and Dean use film to reproduce the magnitude, richness, chaos, and sensory overload characteristic of the New Year’s rituals on the Putian plain—although the final result is still rather less, as they point out, than what you could experience if you lived in a place where ritual opera was performed 250 days a year. Ethnographic Cinema, History, and Anthropology History as process and product strongly affected the ethnographers’ filmmaking. Chio speaks in detail about omitting, condensing, or ignoring history to create portraits of the two villages in her film. Gillette discusses how the desire to show history influenced what kind of footage she used, including period archival footage from locations other than Jingdezhen. Dean and Dean position their work explicitly as a correction to the historical record. They use Kenneth Dean’s voice-over GILLETTE 7 narration to communicate historical processes, coupled with visual images that suggest recent innovation (such as the use of robots in devotional practices). Zito includes printed quotations from classical calligraphy texts to convey continuity between contemporary writing in water and China’s long-standing tradition of calligraphic practice. She insists that “third places” be included in the historical record. While Sniadecki privileges the “here-and-now” of his encounter with migrant workers, he, like the other filmmakers, understands his film as a contribution to the historical archive. Sniadecki emphasizes how what he calls the density of the image provides resources for alternative historical narratives. Christian Churchill (2005) has written that the ethnographer’s mind operates as a “transitional space” between historical event and its representation. Between the “capturing” of field data and the published ethnography comes a “transformational process” that rests on the ethnographer’s capacity for empathy and her ability to be at home in two “languages,” that of the ethnographic subject and that of the audience. Nichols (2010:17), discussing filmmakers, uses the metaphor of the tour guide, who directs how film viewers stroll through the cinematic world. In ethnographic film, this world is “stuck” to the historic world, but mediated by the filmmaker. What these characterizations suggest is that ethnographer–filmmakers must be conscious of, and responsible to, a set of social relationships that constitute the historic world. The filmmakers’ sensitivity to a particular set of human relationships that were their field research informs how and what they craft, evoke, and translate, that is, “carry across” (trans-latum) the more transient social relationship that they form with viewers. The authors in this volume speak concretely about the social relationships that informed their filmmaking at every stage of the process from production, through postproduction, to film screenings and subsequent conversations. They describe in detail how participants’ concerns, the critiques of other filmmakers, and their understandings of their audiences shaped their work. The New China and the New Ethnographic Cinema Nary a day goes by without the PRC appearing in the headlines of major newspapers around the world. Today the topics were air pollution in Chinese cities and how the Chinese Communist Party can sustain rapid economic growth and liberalization while retaining a 8 VISUAL ANTHROPOLOGY REVIEW Volume 30 Number 1 Spring 2014 monopoly over political power (Buckley 2013; Guardian 2013). Tomorrow will bring other stories. With China’s meteoric rise to become an economic powerhouse and major player in global politics, the PRC spends a lot of time in the media spotlight, perhaps more than ever before. Ethnographers working in China can and should contribute to public dialogue and understanding about Chinese society. Film is a particularly compelling medium for ethnographers to evoke experiences and share what they know. Cinema addresses the whole body and mind, affording opportunities for experience, reflection, and public debate. As ethnographer– filmmakers, we can take advantage of our scholarly training to illuminate the conditions of our knowledge production. The articles found here exemplify how we can enhance public understandings of our ethnographic films by clearly and concretely discussing our filmmaking practices. Acknowledgments The author would like to thank Janet Hoskins, Nancy Lutkehaus, Gary Seaman, the University of Southern California China Institute, and the USC Center for Visual Anthropology for organizing the conference and screenings entitled “Cultural Dimensions of Visual Ethnography: US-China Dialogues,” which was the genesis of this project (April 8–11, 2010). I thank the Hurford Arts and Humanities Center, the Center for Peace and Global Citizenship, and the Distinguished Visitors Fund of Haverford College for their support of the film festival and workshop “Forbidden No More: The New China in Ethnographic Film” (February 24–26, 2012). This volume would not have been possible without all the enthusiastic participants in that event. In particular, I am grateful to the ethnographer–filmmakers who attended: Tami Blumenfield, Jenny Chio, Kenneth Dean, Benjamin Gertsen, Stevan Harrell, Tik-sang Liu, J.P. Sniadecki, and Angela Zito. I thank the editors of Visual Anthropology Review and anonymous reviewers for the special issue, who contributed useful feedback and suggestions for the final edition. Finally, I thank the Swedish Collegium for Advanced Study and the EURIAS Fellowship Programme for providing the resources needed to complete this work. Notes 1 2 I use the word film to mean all forms of film and digital video. All of the filmmakers whose work appears in this volume worked in digital video. The international Sino-Swedish Expedition to northwest China, led by Swedish explorer and geographer Sven Hedin and including the Danish ethnographer Henning Haslund Christensen, Danish cinematographer Paul Karl Lieberenz, and Chinese archaeologist Xu Xusheng, also produced some films during their stay in the Gobi Desert and Tarim Basin between 1927 and 1929 (http://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chinesisch-Schwedische_ Expedition, Chen and Lei 2009:73–75, http://www .olympiabookfair.com/antiquarian-books/d/ cinematography-archive-featuring-the-travels-and-works -of-paul-lieberenz-from-1923-to-1954-includes-originalphotographs-letters-journals-passports-original-filmtypescripts-copper-engraved-plates-etc/49176). The films were first screened in 1929. I have never seen them, but Chen and Lei (2009:73–75) identify them as “anthropological.” While the online descriptions mention the stunning landscape, expedition caravan, and a sandstorm, they say nothing about more recognizably ethnographic content. The evidence also suggests that these films were in fact shot later than Gamble’s. References Anagnost, Ann 1985 Hegemony and the Improvisation of Resistance: Political Culture and Popular Practice in Contemporary China. Ph.D. dissertation, UMI Dissertations. 1987 Politics and Magic in Contemporary China. Modern China 13(1):41–61. Banks-Smith, Nancy 1983 Inside China. Guardian, April 28: 12. Berry, Chris, Lu Xinyu, and Lisa Rofel, eds. 2010 The New Chinese Documentary Film Movement: For the Public Record. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press. Blumenfield, Tami 2010 Scenes from Yongning: Media Creation in China’s Na Villages. Ph.D. dissertation, Proquest. Buckley, Chris 2013 Chinese Leader’s Economic Plan Tests Goal to Fortify Party Power. New York Times. http://www .nytimes.com/2013/11/07/world/asia/a-clash-ofgoals-for-chinas-leader.html?hpw&rref=world (accessed November 7, 2013). Chang, Yung 2007 Up the Yangtze. 93 min. Montreal: Eye Steel Film. Chen, Jingyuan, and Liangzhong Lei 2009 A History of Visual Anthropology in China. In Cultural Glimpses: Film Festival of the 16th World Congress of IUAES. Zhuang Kongshao, ed. Pp. 64–152. Kunming: Yunnan University Press. Chen, Richard, and Frank Tsai, with Bernard Gallin, Sheldon Appleton, Albert Ravenhold, and Norma Diamond 1974 Taiwan Series (People Are Many, Fields Are Small [32 min.], They Call Him Ah Kung [24 min.], Wet Rice Culture [17 min.], A Chinese Farm Wife [17 min.], The Rural Cooperative [15 min.]). Chu, Yingchi 2007 Chinese Documentaries: From Dogma to Polyphony. New York: Routledge. New Ethnographic Film in the New China Churchill, Christian 2005 Ethnography as Translation. Quantitative Sociology 28(1):3–24. Du, Rongkun, and Guanghai Yang 1989 The Development of Ethnocinematography in China. CVA Newsletter, May 1981:21–26. Feuchtwang, Stephan 1975 Review of Dragons on the Sea. RAIN 6:9. 1977 Review of Da Jiu. RAIN 23:6–7. 1983 Review of The Kazakhs of China. RAIN 57:10. Gibb, Hugh, with Marjorie Topley 1971 Ways of the Middle Kingdom. 50 min. BBC Television. Gibb, Hugh, with Barbara Ward 1973 Dragons on the Sea. 50 min. BBC Television. Gibb, Hugh, with Hugh Baker 1977 Da Jiu: Dragons, Gods, and Ancestors. 50 min. BBC Television. Gillette, Maris Boyd 2009 Broken Pots Broken Dreams. 26 min. Philadelphia. Ginsburg, Faye 1994 Culture/Media: A (Mild) Polemic. Anthropology Today 10(2):5–15. Gonzales, Nancie 1975a Review of Breaking the Blood Bowl by Gary Seaman. American Anthropologist 77(1):193– 194. 1975b Review of Blood, Bones and Spirits by Gary Seaman. American Anthropologist 77(1):194. 1975c Review of Curing Séance by Gary Seaman. American Anthropologist 77(1):178–179. Graves, William 1987 Review of All Under Heaven by Carma Hinton and Richard Gordon. American Anthropologist 89(1):253–254. Guardian 2013 China Cracks Down on Emissions to Combat Choking Smog. Guardian. http://www .theguardian.com/world/2013/nov/06/chinaemissions-smog-air-pollution-traffic-factoryrestrictions (accessed November 6, 2013). Harrell, Stevan 1989 Ethnicity and Kin Terms among Two Kinds of Yi. In Ethnicity and Ethnic Groups in China. Chiao Chien and Nicholas Tapp, eds. Pp. 179–198. Hong Kong: Chinese University Press. 1990 Ethnicity, Local Interests, and the State: Three Yi Communities in Southwest China. Comparative Studies in Society and History 32(3):515–548. 1992 Aspects of Marriage in Three Southwestern Villages. China Quarterly 130:323–337. Heider, Karl G. 2006 [1976] Ethnographic Film. Austin: University of Texas Press. Henley, Paul 1985 British Ethnographic Film: Recent Developments. Anthropology Today 1(1):5–17. GILLETTE 9 Hermer, Carol 2009 Reading the Mind of the Ethnographic Filmmaker. In Viewpoints: Visual Anthropologists at Work. Mary Strong and Laena Wilder, eds. Pp. 121–139. Austin: University of Texas Press. Hinton, Carma, and Richard Gordon 1984–1987 One Village in China Series (Small Happiness [58 min.], All Under Heaven [58 min.], To Taste 100 Herbs [58 min.], First Moon [30 min.]). Brookline, MA: Long Bow Group. 1995 The Gate of Heavenly Peace. 180 min. Brookline, MA: Long Bow Group. 2003 Morning Sun. 120 min. Brookline, MA: Long Bow Group. Hu, Tai-li 1985 The Return of Gods and Ancestors: Paiwan’s Five Year Ceremony. 35 min. Taiwan. 1993 Voices of Orchid Island. 73 min. Taiwan. Ikels, Charlotte 1985 Review of Gui Dao—On the Way by George Dufaux, Women in China Today by Nippon A-V Productions, Wuxing the People’s Commune by Boyce Richardson and Tony Ianzelo and Small Happiness by Carma Hinton and Richard Gordon. American Anthropologist 87(3):739– 741. Jenkins, Alan 1986 Disappearing World Goes to China: A Production Study of Anthropological Films. Anthropology Today 2(3):6–13. Kehl, Frank 1970 Hungry Ghosts. 30 min. Hong Kong: Center of Asian Studies, University of Hong Kong. 1984 Review of Stilt Dancers of Long Bow by Richard Gordon and Carma Hinton. American Anthropologist 86(2):516–517. Loizos, Peter 1993 Innovation in Ethnographic Film. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. MacDougall, David 1998 Transcultural Cinema. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. Martinez, Wilton 1992 Who Constructs Anthropological Knowledge? Toward a Theory of Ethnographic Film Spectatorship. In Film as Ethnography. Peter Crawford and David Turton, eds. Pp. 131–161. Manchester, UK: Manchester University Press. Miller, Norman, with Richard Chen, Loren Fessler, George Chang, and C. Fred Blake 1974 China Coast Series (Island in the China Sea [32 min.], Hoy Fok and the Island School [32 min.], China Coast Fishing [19 min.], Three Island Women [17 min.], The Island Fishpond [13 min.]). Hong Kong. Mirsky, Jonathan 1983 Life with the Dings. Observer, May 15: 30. 10 VISUAL ANTHROPOLOGY REVIEW Volume 30 Number 1 Spring 2014 Moggan, Julie 2005 Reflections of a Neophyte: A University versus a Broadcast Context. In Visualizing Anthropology. Anna Grimshaw and Amanda Ravetz, eds. Pp. 31–41. Bristol, UK: Intellect Books. Nichols, Bill 1991 Telling Stories with Evidence and Arguments. In Representing Reality. Pp. 107–133. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. 2010 Engaging Cinema. New York: W. W. Norton. Observer 1973 Review of Dragons on the Sea. 35. Today’s Television. Peled, Micha 2005 China Blue. 86 min. San Francisco: Teddy Bear Films. Schein, Louisa 1989 The Dynamics of Cultural Revival among the Miao in Guizhou. In Ethnicity and Ethnic Groups in China. Chiao Chien and Nicholas Tapp, eds. Pp. 199–212. Hong Kong: Chinese University Press. 2000 Minority Rules: The Miao and the Feminine in China’s Cultural Politics. Durham, NC: Duke University Press. 2013 Ethnographic Representations across Genres: The Culture Trope in Contemporary Mainland Media. In The Oxford Handbook of Chinese Cinemas. Carlos Rojas, ed. Pp. 507–525. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Seaman, Gary 1974 Chinese Popular Religion Series (The Rite of Cosmic Renewal [35 min.], The Temple of Lord Kuan [24 min.], Blood Bones and Spirits [36 min.], Weapons [25 min.], Feng Shui: Chinese Geomancy [16 min.], The Luck of the Lord of the Land [15 min.], Curing Séance [15 min.], Wedding Feast [24 min.], Chinese Funeral Ritual [24 min.], Breaking the Blood Bowl [18 min.]). 1977 Films in the Field: Audiovisual Techniques and Technology in Anthropology. Reviews in Anthropology 4:359–368. Strauch, Judith 1977 Review of the China Coast Series by Norman Miller. American Anthropologist 79(3):757–758. Watson, Rubie 1983 Review of Inside China. RAIN 57:9–10. Weakland, John 1966 Themes in Chinese Communist Films. American Anthropologist 68(2):477–484. Wolf, Margery, and Arthur Wolf 1977 Review of the Taiwan Series by Richard Chen. American Anthropologist 79(3):756. Woodhead, Leslie, with Barbara Hazard 1983a Inside China: Living with the Revolution. 52 min. London: Granada Productions. 1983b Inside China: The Newest Revolution. 50 min. London: Granada Productions. Yan, Yunxiang 1992 The Impact of Rural Reform on Economic and Social Stratification in a Chinese Village. Australian Journal of Chinese Affairs 27:1–23. 1996 The Flow of Gifts: Reciprocity and Social Networks in a Chinese Village. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. Yang, Rubie, with Thomas Lennon 2006 The Blood of Yingzhou District. 39 min. Thomas Lennon Films. Zhang, Yinjin 2004a Chinese National Cinema. New York: Routledge. 2004b Styles, Subjects, and Special Points of View: A Study of Contemporary Chinese Documentary. New Cinemas 2(2):119–135. Zhuang, Kongshao, ed. 2009 Cultural Glimpses: Film Festival of the 16th World Congress of IUAES. Kunming: Yunnan University Press. Zito, Angela 2013 On Aphasia: Indices of Things We Would Rather Not Know. Love of Sun, a multimedia online exhibit curated by Rachel Kennedy. http://loveofsun.org/ Article_Zito_Angela.html (accessed November 1, 2013).