RN-BSN Faculty Evaluation of Self-Reflective Journals

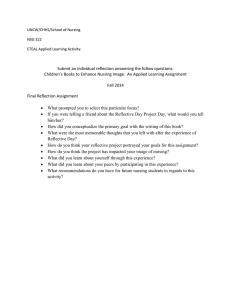

advertisement