CMB Presentation Hofstede

advertisement

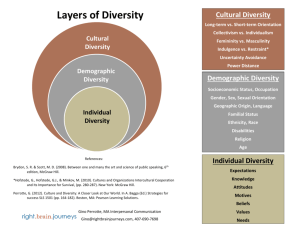

Kolman, L., Noorderhaven, N. G., Hofstede, G., & Dienes, E. (2003). Cross-cultural differences in Central Europe. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 18(1), 76-88. Content • Research Questions and Background • Theoretical Background • Analytical Framework • Research Method • Empirical Result • Implication for Research and Management • Critical assessment Research Questions and Background • Research Question How do the cultural differences between 4 EU nominees link with their expectations regarding the future membership? • Research Gap Survey group consisted of Business and Economics Students only. This research fails to account for individual references as it considers only the nationals of that country. • Background The survey was conducted in four countries, i.e. Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, and Slovakia. These countries were specifically chosen as they were the ones nominated for inclusion in the European Union. Netherlands was also surveyed alongside the 4 countries, to calibrate data as a controlled variable group. Theoretical Background • Frame of reference: Hofstede's (1980) study of 50 countries and 3 regions is the main reference that attempt to estimate the impact of differences on national cultures on management. • Hofstede (2001) brought many replications which used the indices developed from the previous study. Analytical Framework: 5 Dimensions Power Distance • The five dimensions of culture are examined to study the cultural differences among 5 European countries (Hofstede, 1980) Long- vs Short-term orientation • The fifth dimension (Long- vs short-term orientation) is based on a work of group of scholars with a Chinese frame of mind (The Chinese Cultural Connection, 1987). Masculinityfemininity Individualismcollectivism Cultural Differences Uncertainty avoidance Research Method • Data The data were collected from a sample of 500 university students from 5 countries (around 100 from each country) of Business and Economics background, Valid nationals only. Strategy of matched samples (Hofstede, 1991) applied to rule out the sources of variation of no interest (for example : profession, age) • Measurement Value survey module 1994 (VSM 1994; Hofstede, 1994) : A revised version of an earlier questionnaire based on questions used in the original IBM research (Hofstede, 2001) Included the items to measure the fifth dimension, long vs short-term orientation. Calibration process (using data of Netherlands) adapted to make the scores comparable with those reported in Hofstede (2001) Description of Samples • To check with the age difference, the age categories were correlated with the VSM 1994 as there was no consistent pattern over countries. So it was concluded there was no systematic relationship between culture and age. • Due to substantial difference between countries in the proportion of male and female respondent. The calculations were made and it was drawn in the methodology recommended by Noorderhaven and Tidjani (2001) that men and women have equal weight in the scores calculated for all the countries. Empirical Result Dimensions The Netherland (Uncalibrated) Power distance 14 Individualism-collectivism 85 Uncertainty avoidance 37 Masculinity-femininity -17 Long- vs short-term orientation 41 Table II-a Empirical Result • The scores (Table II) were calibrated to compare it with Hofstede (2001); The Dutch sample was used. • In order to do so, the difference between the scores obtained for The Netherlands in this study (Table II-a) and those of the original IBM study were added or subtracted from the scores obtained for the other countries. • For example (Power Distance, The Netherlands) IBM study score : 38 This study score : 14 Correction factor : (38-14) = +24; upward adjustment. Empirical Result • It comes to a finding that Slovakia which was compared to Hungary, Poland , Czechia scores at the extreme in the four dimensions that off five. 1. Power Distance • All four countries show relatively large power distance • Biggest : Slovakia Slovakia’s strong patriarchy (Musil, 1993) • Smallest : Poland Appreciate to be advised and have a good relationship with their manager. However, management style tend to be autocratic (Hickson and Pugh, 1995; Jankowicz, 1994; Jankowicz and Petti, 1993; Zalezka, 1996) Empirical Result • 2. Individualism-collectivism • Most individualistic: Czechia Emphasis on individual rights and responsibilities (Kruzele, 1995) • Most collectivistic: Slovakia Modernization had implications on attitude towards work. Ideal job : More importance to good physical work conditions than spending time with family. (Musil, 1993) 3. Uncertainty avoidance • Slovakia shows remarkably weak uncertainty avoidance. Fact that one can be a good manager without having precise answers to most questions that subordinates may raise about their work • Czechia - Emphasis on equality and security of living (Musil, 1993); Hungary - Notion that they are surrounded by enemies and minorities abroad are treated unfairly (Csepeli, 1991) and Poland display strong uncertainty avoidance Empirical Result 4. Masculinity-femininity • All four countries are in high position of masculinity • Most Masculinity: Slovakia ideal job description : working with people who cooperate with others well is less important • Least Masculinity: Czechia Agree more with “when people have failed in life it is often their own fault” statement Disagree more with “most people can be trusted” statement The managers see themselves as ”strong male individuals” 5. Long- vs short-term orientation • Strong Long-term orientation: Hungary Hungarian’s private life value thrift and persistence Hierarchy, a peaceful, harmonic life is valuable (Simon, 1993) • Strong Short-term orientation: Czechia The managers often choose short-term profits and spend time looking at the past (Chadabra, 1994) Empirical Result Calibrated Positions of the countries (From Table 3) Power Distance Long- vs Short-term orientation Individualism-Collectivism Masculinity-Femininity Czechia Uncertainty avoidance Hungary Poland Slovakia Calibrated Positions of the countries Small Power Distance Big Power Distance S H C P Collectivism Individualism C H P S Weak Uncertainty avoidance Strong Uncertainty avoidance H S C P Masculinity S H femininity P C short-term orientation Long-term orientation H S P C S = Slovakia C = Czechia H = Hungary P = Poland Implications for Research and Management • Key Finding Even after the systemic changes around 1990, there are notable cultural differences between Central European countries and Western Europe (represented by The Netherlands). There are significant differences between the four Central European countries. • Implications for research Developed perspective about the cultural orientations between the nominated countries, essential for their political and economic processes of integration within Europe, and also helping in acquiring appropriate cross-cultural skills. • Implications for management The observations seem to suggest that a keen eye needs to be kept on future value and cultural shifts in these countries, as the cultural differences between Central and Western European countries may influence the outcomes of processes of politico-economic integration. Critical Assessment • Reliability: As this study was done in 2002, it is impossible to freeze a social setting and circumstances of an initial study, Hofstede introduced a sixth dimension in 2010. (Indulgencerestraint) (Hofstede et. al, 2010) • External Validity: Low number of respondents (only 100 each country) limited only to economics and business university students. More research is required to understand the causal relationship as it would be dangerous to treat the central European countries as a homogeneous group. • Construct Validity: The instrument used in the study (Value Survey Module ,VSM 1994) is a revised version of a questionnaire used in the original IBM research. Some items have been taken from the original study while additional items were prepared and tested in various replication studies (includes items to measure the fifth dimension). This will help in data collection for any future study. • Internal Validity: This study does not take into account the individual differences of nationals of a country. Numerical variables (e.g. age) are carefully selected from a group of university students in order to employ a strategy of matched samples whereas other section of the society is neglected in the research. Moreover, Netherlands was selected as a standard to calibrate the results with the original study of Hofstede 1980. Choosing another country may yield different results. Q&A References • Chadabra, P.G. (1994), “Managers and the process of management: the case of Czechoslovakia”, in Tesar, G. (Ed.), Management Education and Training: Understanding Eastern European Perspectives, Krieger, Malabar, FL, pp. 53-65. • Chinese Culture Connection (1987), “Chinese values and the search for culture-free dimensions of culture”, Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, Vol. 18, pp. 143-74. • Csepeli, G. (1991), “Competing patterns of national identity in post-communist Hungary”, Media, Culture and Society, Vol. 13, pp. 325-39. • Hickson, D.J. and Pugh, D.S. (1995), Management Worldwide: The Impact of Societal Culture on Organizations Around the Globe, Penguin Books, London. • Hofstede, G. (1980), Culture‘s Consequences: International Differences in Work-related Values, Sage, Beverly Hills, CA. References • Hofstede, G. (1991), Cultures and Organization: Software of the Mind, McGraw-Hill, London. • Hofstede, G. (1994), Value Survey Module 1994 Manual, Institute for Research on Intercultural Cooperation, Maastricht. • Hofstede, G. (2001), Culture’s Consequences: Comparing Values, Behaviors, Institutions, and Organizations Across Nations, 2nd ed., Sage, Thousand Oaks, CA. • Hofstede, G.H., Hofstede, G. J. and Minkov, M. (2010), Cultures and Organizations. 3rd edn. New York: McGraw-Hill Professional Publishing. • Jankowicz, A.D. (1994), “The new journey to Jerusalem: mission and meaning in the managerial crusade to Eastern Europe”, Organization Studies, Vol. 15, pp. 479-507. • Jankowicz, A.D. and Pettitt, S. (1993), “Worlds in collusion: an analysis of an Eastern European management development initiative”, Management Education and Development, Vol. 24, pp. 93104. • Kolman, L., Noorderhaven, N. G., Hofstede, G., & Dienes, E. (2003). Cross-cultural differences in Central Europe. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 18(1), 76-88. References • Kruzela, P. (1995), “Some cultural aspects on Czech and Russian management”, Proceedings of the 5th SIETAR Europa Symposium, Prague, pp. 222-35. • Musil, P. (1993), “Czech and Slovak society”, Government and Opposition, Vol. 28, pp. 479-95. • Noorderhaven, N.G. and Tidjani, B. (2001), “Culture, governance, and economic performance: an explorative study with a special focus on Africa”, International Journal of Cross Cultural Management, Vol. 1, pp. 31-52. • Simon, N.G. (1993), “Post-paternalist political culture in Hungary: relationship between citizens and politics during and after the “Melancholic Revolution” (1989-1991)”, Communist and PostCommunist Studies, Vol. 26, pp. 226-38. • Zalezka, K.J. (1996), “Cross-cultural interaction between Polish and expatriate managers in subsidiaries of multinational organizations in Poland”, paper presented at the Academy of International Business Conference, Birmingham.