3.1 - Adaptations for Gas Exchange Eduqas Notes

advertisement

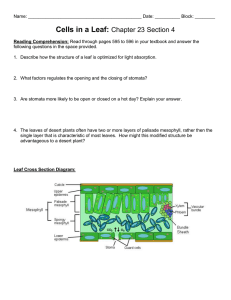

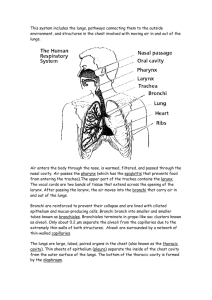

3.1 Adaptions for Gas Exchange The adaptations for gas exchange which allow an increase in body size and metabolic rate The need for specialised exchange surfaces arises as the size surface area to volume ratio of an organism increases. In single celled organisms, substances can easily enter the cell as the distance that needs to be crossed is short. In multicellular organisms that distance is much larger, so they require specialised exchange surfaces for efficient gas exchange of carbon dioxide and oxygen. Features of an efficient exchange surface include large surface area or folded membranes An efficient exchange surface should also be thin to ensure that the distance that needs to be crossed by the substance is short. The exchange surface also requires a good blood supply/ventilation to maintain a steep gradient Gas exchange in small animals across their general body surface Small animals have a small surface area:volume ratio so they can utilise diffusion The comparison of gas exchange mechanisms in Amoeba, flatworm and earthworm Amoeba: Amoeba is a unicellular organism which lives in fresh water. Respiration takes place by diffusion through its cell membrane The oxygen gas diffused inside the body is used up by amoeba. Flatworm: Gas exchange by direct diffusion across surface membranes Every cell in the body is close to the external environment. Their cells are kept moist so that gases diffuse quickly via direct diffusion. Their flat shape increases the surface area for diffusion, ensuring that each cell within the body is close to the outer membrane surface and has access to oxygen. Earthworm: Diffusion from the soil Requires soil to be moist The common features of the specialised respiratory surfaces of larger animals and the adaptation of respiratory surfaces to environmental conditions - fish have gills for aquatic environments and mammals have lungs for terrestrial environments Cartilage: supports the trachea and bronchi and helps prevent the lungs from collapsing in the event of pressure drop during exhalation. Ciliated epithelium: present in bronchi, bronchioles and trachea, involved in moving mucus along to prevent lung infection by moving it towards the throat where it can be swallowed. Goblet cells: present in the trachea, bronchi and bronchioles and secrete mucus to trap bacteria and dust to reduce the risk of infection with the help of lysozymes which digest bacteria. Smooth muscle: contract so can constrict the airway, thus controlling its diameter as a result and thus controlling the flow of air to and from the alveoli. Elastic fibres: stretch when we exhale and recoil when we inhale thus controlling the flow of air. The need for large active animals with high metabolic rates to have ventilating mechanisms to maintain gradients across respiratory surfaces Ventilation in bony fish and comparison of counter current flow with parallel flow Fish have a small surface area to volume ratio but have an impermeable membrane so gases can’t diffuse through their skin. Bony fish have four pairs of gills, each gill supported by an arch. Along each arch there are multiple projections called gill filaments, with lamellae on them which participate in gas exchange. Blood and water flow across the lamellae in a counter current direction meaning they flow in the opposite direction to one another. o This ensures that a steep diffusion gradient is maintained so that the maximum amount of oxygen is diffusing into the deoxygenated blood from the water. The gill filaments/projections are held apart by water flow. Therefore, in the absence of water they stick together, thus meaning fish cannot survive very long out of water. Ventilation is required to maintain a continuous unidirectional flow. Ventilation begins with the fish opening its mouth followed by lowering the floor of buccal cavity. This enables water to flow in. Afterwards, fish closes its mouth, causing the buccal cavity floor to raise, thus increasing the pressure. The water is forced over the gill filaments by the difference in pressure between the mouth cavity and opercular cavity. The operculum acts as a valve and pump and lets water out and pumps it in. The structure and function of the human breathing system, including examination of microscope slides of T.S. lung and trachea The lungs are paired lobed structures with large surface area, located in the chest cavity Lungs are surrounded by a rib cage to protect them External and internal intercostal muscles between the ribs contract to raise and lower the ribcage respectively. A structure called the diaphragm separates the lungs from abdomen area. The air enters through the nose trachea bronchi bronchioles Gas exchange takes place in the walls of alveoli, which are tiny sacs filled with air. The airways are held open with the help of a rings of cartilage Trachea and bronchi are similar in structure, with the exception of size – bronchi are narrower. o They are composed of several layers which together make up a thick wall. o The wall is mostly composed of cartilage, in the form of incomplete C rings. o The inside surface of the cartilage is a layer of glandular and connective tissue, elastic fibres, smooth muscle and blood vessels. This is referred to as the ‘loose tissue’. o The inner lining is an epithelial layer composed of ciliated epithelium and goblet cells. o The bronchioles are narrower than the bronchi. Only the larger bronchioles contain cartilage. Their wall is made out of smooth muscle and elastic fibres. The smallest of bronchioles have alveoli clusters at the ends. o The alveoli are adapted for transport because they are very thin (one cell thick), surrounded by capillaries (also only one cell thick) to reduce the diffusion distance for gases, and the constant blood supply by capillaries means that a steep concentration gradient is constantly maintained. Ventilation in humans and how gases are exchanged The flow of air in and out of the alveoli is referred to as ventilation and is composed of two stages; inspiration and expiration. Inspiration: o External intercostal muscles contract and internal muscles relax (antagonistic muscles), causing the ribs to move up and out. The diaphragm contracts and flattens. This increases the volume inside the thorax, which lowers the pressure. The difference between the pressure inside the lungs and atmospheric pressure creates a gradient, thus causing the air to be forced into the lungs. Expiration: o Internal intercostal muscles contract and external muscles relax, which lowers the rib cage. The diaphragm relaxes and moves upwards. This decrease the volume inside the thorax, therefore increasing the pressure, forcing the air out of the lungs. The adaptations of the insect tracheal system to life in a terrestrial environment Insects do not possess a transport system therefore oxygen needs to be transported directly to tissues undergoing respiration. This is achieved with the help of spiracles, small openings of tubes, either trachea (larger) or tracheoles (smaller), which run into the body of an insect and supply it with the required gases. Gases move in and out through diffusion, mass transport as a result of muscle contraction and as a result of volume changes in the tracheoles. The structure of the angiosperm leaf The role of leaf structures in allowing the plant to photosynthesise effectively Upper Epidermis: The upper epidermis cells have no chloroplasts so light passes through them easily. Palisade Mesophyll: where most of the photosynthesis takes place in the leaf. The palisade cells have many chloroplasts in their cytoplasm and the box-like shape and arrangement of these cells ensures they are packed tightly together. Spongy Mesophyll: contains large air spaces which are linked to the atmosphere outside the leaf through microscopic pores called stomata on the lower surface. Spongy mesophyll cells also contain chloroplasts and photosynthesis occurs here too. The air spaces reduce the distance carbon dioxide has to diffuse to get into the mesophyll cells and the fact that these cells have fairly thin cell walls which are coated with a film of water together means that gas exchange between air space and mesophyll is speeded up. Lower Epidermis: contains specialised cells called guard cells which enclose a pore called a stoma. Carbon dioxide can diffuse into the leaf through the stomata when they are open (usually at day time) and water evaporates out of the stomata in a process called transpiration. Adaptations of a Leaf for Photosynthesis: Large Surface Area – to maximise light harvesting Thin – to reduce distance for carbon dioxide to diffuse through the leaf and to ensure light penetrates into the middle of the leaf Air Spaces – to reduce distance for carbon dioxide to diffuse and to increase the surface area of the gas exchange surface inside the leaf Stomata – pores to allow carbon dioxide to diffuse into the leaf and water to evaporate out (transpiration) Presence of Veins – veins contain xylem tissue (carries water and minerals to the leaf from the roots) and phloem (transports sugars and amino acids away from the leaf) Chloroplasts – mesophyll cells and guard cells contain many chloroplasts. These organelles contain the light harvesting pigment chlorophyll and are where all the reactions of photosynthesis occur The role of the leaf as an organ of gas exchange, including stomatal opening and closing Leaves have many small holes called stomata which allow gases to enter and exit the leaves. The large number of these means no cell is far from the stomata, reducing the diffusion distance. Leaves also possess air spaces to allow gases to move around the leaf and easily come into contact with photosynthesising mesophyll cells.