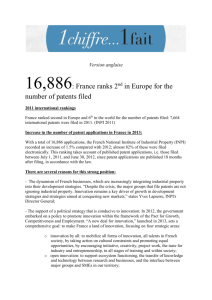

wipo pub econstat wp 23

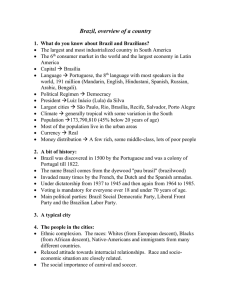

advertisement