Bronfort (2001) Chronic pediatric asthma and chiropractic spinal manipulation - copie

advertisement

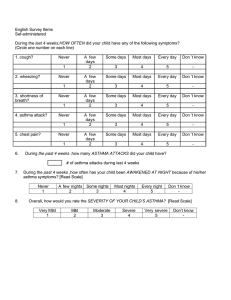

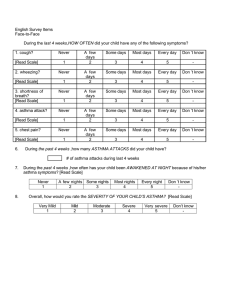

Journal of Manipulative and Physiological Therapeutics Volume 24 • Number 6 • July/August 2001 0161-4754/2001/$35.00 + 0 76/1/116417 © 2001 JMPT ORIGINAL ARTICLES Chronic Pediatric Asthma and Chiropractic Spinal Manipulation: A Prospective Clinical Series and Randomized Clinical Pilot Study Gert Bronfort, DC, PhD,a Roni L. Evans, DC,a Paul Kubic, MD, PhD,b and Patty Filkinb ABSTRACT Objectives: The first objective was to determine if chiropractic spinal manipulative therapy (SMT) in addition to optimal medical management resulted in clinically important changes in asthma-related outcomes in children. The second objective was to assess the feasibility of conducting a full-scale, randomized clinical trial in terms of recruitment, evaluation, treatment, and ability to deliver a sham SMT procedure. Study Design: Prospective clinical case series combined with an observer-blinded, pilot randomized clinical trial with a 1year follow-up period. Setting: Primary contact, college outpatient clinic, and a pediatric hospital. Patients: A total of 36 patients aged 6 to 17 years with mild and moderate persistent asthma were admitted to the study. Outcome Measures: Pulmonary function tests; patient- and parent- or guardian-rated asthma-specific quality of life, asthma severity, and improvement; AM and PM peak expiratory flow rates; and diary-based day and nighttime symptoms. Interventions: Twenty chiropractic treatment sessions were scheduled during the 3-month intervention phase. Patients were randomly assigned to receive either active SMT or sham SMT in addition to their standardized ongoing medical management. Results: It is possible to blind the participants to the nature of the SMT intervention, and a full-scale trial with the described design is feasible to conduct. At the end of the 12-week intervention phase, objective lung function tests and patient-rated day and INTRODUCTION Asthma is a multifactorial condition and the most common chronic disease of childhood.1 Since 1980, the prevalence of pediatric asthma has increased more than 50% and a Wolfe-Harris Center for Clinical Studies, Northwestern Health Sciences University, Bloomington, Minn. b Children’s Health Care, St Paul, Minn. This study was funded by the Foundation for Chiropractic Education and Research. Gert Bronfort, DC, PhD, holds the Greenawalt Research Chair, funded through an unrestricted grant from Foot Levelers, Inc. Submit reprint requests to: Gert Bronfort, DC, PhD, WolfeHarris Center for Clinical Studies, Northwestern Health Sciences University, 2501 West 84th Street, Bloomington, MN 55431. Paper submitted June 5, 2000; in revised form September 5, 2000. doi:10.1067/mmt.2001.116417 nighttime symptoms based on diary recordings showed little or no change. Of the patient-rated measures, a reduction of approximately 20% in β2 bronchodilator use was seen (P = .10). The quality of life scores improved by 10% to 28% (P < .01), with the activity scale showing the most change. Asthma severity ratings showed a reduction of 39% (P < .001), and there was an overall improvement rating corresponding to 50% to 75%. The pulmonologist-rated improvement was small. Similarly, the improvements in parent- or guardian-rated outcomes were mostly small and not statistically significant. The changes in patient-rated severity and the improvement rating remained unchanged at 12-month posttreatment follow-up as assessed by a brief postal questionnaire. Conclusion: After 3 months of combining chiropractic SMT with optimal medical management for pediatric asthma, the children rated their quality of life substantially higher and their asthma severity substantially lower. These improvements were maintained at the 1-year follow-up assessment. There were no important changes in lung function or hyperresponsiveness at any time. The observed improvements are unlikely as a result of the specific effects of chiropractic SMT alone, but other aspects of the clinical encounter that should not be dismissed readily. Further research is needed to assess which components of the chiropractic encounter are responsible for important improvements in patient-oriented outcomes so that they may be incorporated into the care of all patients with asthma. (J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2001;24:369-77) Key Indexing Terms: Asthma; Pilot Projects; Feasibility Studies; Chiropractic Manipulation; Pediatric; Placebo mortality more than 70%.2 The management of asthma has changed substantially since the early 1990s, and national and international guidelines now recommend a stepwise approach to treatment.3 Fundamental to current management is the early introduction of antiinflammatory medication rather than reliance on bronchodilators. Inhaled steroids suppress the inflammation of asthma and effectively control symptoms in most patients. By contrast, inhaled β2-agonists relieve symptoms for a short-term period but do not control the underlying inflammation. Indeed, it has been questioned whether excessive use of inhaled β2-agonists may contribute to the increased morbidity and mortality of the condition.4 Alternative and complementary treatments are commonly used by the general population.5 The dependence on medication and the uncertainty about outgrowing the disease lead many parents of children with asthma to seek these types of 369 370 Journal of Manipulative and Physiological Therapeutics Volume 24 • Number 6 • July/August 2001 Chronic Pediatric Asthma and Chiropractic Spinal Manipulation • Bronfort et al treatments.6-9 There is some evidence from randomized clinical trials (RCT) that acupuncture, yoga, suggestion, hypnosis, massage, and relaxation can be beneficial as adjunctive measures in the management of chronic asthma.6-7 Studies indicate that it is not uncommon for patients with breathing difficulties such as asthma to receive chiropractic care. According to a Danish survey,10 a substantial number of children with chronic asthma receive chiropractic care, and 92% of parents consider this treatment beneficial. A 1998 report of an Australian survey estimated that 1% to 10% of children with asthma receive chiropractic treatment for this condition.9 Several descriptive studies and anecdotal reports in the literature claim positive clinical effect of manual spinal therapy for lung dysfunction and asthma.11-14 A few clinical studies have also addressed the role of spinal manipulative therapy (SMT) in obstructive bronchial disorders.15,16 Increases in vital capacity, total lung capacity, and forced expiratory volume in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease were reported in a controlled trial on the effectiveness of spinal manipulation.15 These improvements were greater than in a control group, although statistical significance was not reached. A preliminary study by Hviid16 showed that chiropractic SMT seemed to improve vital capacity, peak expiratory flow rate, and subjective symptoms in a group of patients with various types of obstructive lung disease. Unfortunately, the small sample size did not allow for definitive conclusions. A pilot study17 of asthmatic patients in a chiropractic clinic found that although chiropractic SMT did not reduce airway obstruction, patients reported subjective reduction in their asthma symptoms. At the time the current study was initiated, only one RCT had assessed the effectiveness of SMT for patients with asthma.18 The crossover trial by Nielsen et al18 was performed on adult patients and found no clinically important change in pulmonary function. A reduction in patient-rated asthma severity and hyperresponsiveness was observed; however, there were no differences between the active and sham SMT phases. In 1993, the authors proposed a prospective case series and pilot study with two objectives. The first was to determine if chiropractic SMT in addition to optimal medical management resulted in clinically important changes in asthma-related outcomes. The second objective was to assess the feasibility of conducting a full-scale RCT in terms of recruitment, evaluation, treatment, and ability to deliver a sham SMT procedure. METHODS Study Sites This study was conducted at the Wolfe-Harris Center for Clinical Studies at Northwestern College of Chiropractic, Bloomington, Minn, and Children’s Health Care, St Paul, Minn (formerly Children’s Hospital). The study was approved by the institutional review boards of both institutions, and informed consent was sought from all study participants and their parents or guardians. Recruitment Patients were recruited through a pediatric pulmonary practice at Children’s Health Care and through newspaper advertising. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria Patients were required to attend 4 baseline appointments during an 8-week period to determine eligibility. Patients were eligible for the study if they were aged 6 to 17 years and had mild or moderate persistent asthma as diagnosed by the pediatric pulmonologist using national guideline criteria.3 Mild persistent asthma was defined as the presence of symptoms more than twice a week but less than once a day, exacerbations that may affect activity, presence of nighttime symptoms more than twice a month, forced expiratory volume in the first second (FEV1) or peak expiratory flow (PEF) ≥ 80% of predicted, and PEF variability of 20% to 30%. Moderate persistent asthma was defined as the presence of daily symptoms, exacerbations 2 or more times a week, exacerbations that may affect activity, presence of nighttime symptoms more than once a week, FEV1 or PEF 60% to 80% of predicted, and PEF variability >30%. Patients were also required to have the presence of spinal dysfunction as determined by a chiropractic physician. Patients were excluded from study participation if they had any of the following: other clinically important medical diseases, obstruction of large or small airways from conditions other than asthma, previous chiropractic SMT, any contraindications to manual SMT, oral steroid therapy exceeding 30 days during the past year, abnormal chest radiographs, and concurrent immunotherapy. Randomization The randomization schedule was computer-generated. The allocation ratio was 2:1 so that the number of patients in the active SMT group was twice the number in the sham SMT group. Stratification by age (5 to 12 years and 13 to 17 years) was performed with permuted block randomization to ensure equal numbers of participants in each age group. Each treatment allocation was placed in a sealed, opaque envelope and was opened by treating clinicians at the end of the fourth baseline visit once eligibility had been confirmed. Treating clinicians were blinded to upcoming treatment assignments and remained unaware of the block size. Interventions All patients were medically managed throughout the study. The medical treatment followed the standardized guidelines for the management of chronic asthma in children.3 Both mild and moderate persistent asthmatic patients were prescribed maintenance or controlling therapy as well as β2agonists on an as-needed basis for symptom relief, not to exceed 3 to 4 times a day. The maintenance therapy included several drug options. For mild persistent asthma, daily antiinflammatory medication was used in the form of inhaled corticosteroids in low dose or cromolyn sodium or occasionally sustained-released theophylline. For moderate Journal of Manipulative and Physiological Therapeutics Volume 24 • Number 6 • July/August 2001 Chronic Pediatric Asthma and Chiropractic Spinal Manipulation • Bronfort et al persistent asthma, the daily antiinflammatory medication was inhaled corticosteroids in higher dose or cromolyn sodium or occasionally sustained-released theophylline, and often long-acting β2-agonists either inhaled or in tablet form. During exacerbations lasting for several days, short courses of systemic corticosteroid therapy were used. For both types of patients with asthma, antiallergic medications were used when indicated during allergy seasons. Chiropractic treatment. One licensed, experienced chiropractor delivered both active and sham treatments in the study. Care was taken to spend the same amount of time with all patients. A total of 20 treatment sessions were scheduled for each patient during the 3-month intervention phase. Spinal manipulation. Manipulation of dysfunctional joints of the spine and pelvis was carried out with the patient placed on a chiropractic treatment table with separate cushion sections for the cervical, thoracic, and lumbar spine. Drop mechanisms are built into these sections, enabling them to be quickly released and lowered 2 to 3 cm when the force from the manual treatment exceeds a certain preset level according to the weight of the patient. This technique is used to facilitate and accentuate the specific manual treatment. The manual spinal thrusting technique used a specific contact over a vertebral osseous process, muscle, or ligament and introduced a force into the selected vertebral or sacroiliac joint. This manual spinal treatment was carried out with a high-velocity, low-amplitude thrust, most commonly by means of a short-lever technique. Sham spinal manipulation. Patients in the sham manipulation group received light manual contact to the spine with no manipulative thrust. For this procedure, a treatment table with releasable drop sections was also used. The patient was first placed prone for the thoracic and lumbar spine contacts and then on his or her side for the cervical spine contact. The sham treatment consisted of gentle manual pressure over a spinal contact point with one hand, while the other hand pushed on the drop section with the purpose of releasing it. The tension of the drop section was set just great enough not to be released by the weight of the patient. As a result of this procedure, the patient experienced a rapid, momentary change in position of the spinal section under influence, similar to an active treatment. Similar manual maneuvers have been used in previous studies and have been shown to be acceptable placebo treatments. Outcome Measures Evaluation of pulmonary function. Certified pulmonary technicians at the participating hospital’s respiratory laboratory performed pulmonary function tests. These results were measured at baseline and after 12 weeks of treatment. Tests included spirometry, forced volume loop, lung volume, plethysmography, and nonspecific bronchial challenge with exercise challenge. Spirometry and forced volume studies were performed with a pneumotachometer, its signal integrated with a computerized pulmonary function test system. The lung function measurements were conducted at approximately the same time of day. The mean of two repeated measurements was used for calculation. The following protocol was administered for withdrawal of medication before lung function tests and nonspecific bronchial challenges: oral β2-agonists for 24 hours, inhaled bronchodilators for 6 hours, and antihistamines and long-acting theophylline for 48 hours. The pulmonary technicians were blinded to the treatment allocation of the patients. Diaries and peak expiratory flow rate. Patients were given an asthma diary at the first baseline visit and were instructed on how to perform daily peak expiratory flow readings (PEFR) with the Truzone peak flow meter (Monaghan Medical Corporation). Patients were asked to record day and nighttime peak flow and symptoms and daily β2 inhaler use for the entire 12week treatment period. Compliance with filling out the diary and peak flow meter technique was checked periodically. Questionnaires. Questionnaires assessing quality of life and asthma severity and improvement were administered twice at baseline and after 12 weeks of treatment. A postal questionnaire assessing asthma severity and improvement was administered 1 year after the end of treatment. Patient-rated, asthma-specific quality of life was measured by an interviewer-administered questionnaire developed by Juniper et al.19 Parent-/guardian-rated quality of life was measured by a self-report questionnaire developed by the same investigators.20 Patient-rated and parent-/guardian-rated asthma severity and improvement were also measured with selfreport questionnaires. Severity was assessed with an 11-box scale,21 where 0 = no symptoms and 10 = worst symptoms possible. Improvement was measured with a 9-point scale ranging from “no symptoms: 100% better” to symptoms “twice as bad: 100% worse.” Patients, parents/guardians, and interviewers were all blinded to the patients’ treatment assignment. Success of patient blinding. After the end of the 12 weeks of treatment, patients and their parents/guardians were asked to indicate which treatment group they thought patients had received. Statistical Analyses Based on sample size calculations, 20 patients were required in the active treatment group, which constituted the prospective case series, to detect a 15% to 25% change in most of the outcome measures. Ten patients were determined sufficient for the sham treatment group to assess the feasibility of delivering a sham procedure. Allowing for a 20% dropout rate, 36 patients were needed for the study. Statistical analyses of data from patients in the active treatment group included paired Student t tests comparing baseline values with posttreatment values at 12 weeks. P values < .01 were considered statistically significant for the 5 main outcome variables: morning and evening PEFR, patient-rated asthma severity, as-needed β2 bronchodilator use, and airway responsiveness. Confidence intervals of 95% were calculated for change scores in FEV1, FEF25-75, general health status, symptoms, and asthma-specific quality of life (patientand parent-/guardian-rated). Diary data from the 2 weeks before randomization and the 11th and 12th weeks after 371 372 Journal of Manipulative and Physiological Therapeutics Volume 24 • Number 6 • July/August 2001 Chronic Pediatric Asthma and Chiropractic Spinal Manipulation • Bronfort et al Table 1. Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics (means and SD unless otherwise noted) Characteristic Age (SD) (y) Age ≤ 12 (y) (%) Male child (%) Moderate persistent asthma (%) Mild persistent asthma (%) Patient-rated Asthma severity (0-10) Quality of life (1-7)* Symptoms Activity Emotions Overall score Parent-/guardian-rated Asthma severity (0-10) Quality of life (1-7)* Activity Emotions Overall score FEV1 % predicted FVC % predicted FEV1/FVC FEF25-75 predicted PEFR AM L/min PEFR PM L/min Diary scores (0-4) Wheezing Shortness of breath Coughing Disturbed sleep Feeling of panic Restricted activity β2-agonist use: no. of puffs/d Age when diagnosed with asthma (y) Age when asthma symptoms started (y) Active SMT (n = 22) Sham SMT (n = 12) 10.4 (3.1) 16 (73) 13 (59) 14 (64) 8 (36) 10.6 (3.1) 8 (67) 6 (50) 10 (83) 2 (17) 3.6 (1.5) 2.4 (2.6) 5.3 (1.1) 4.6 (1.1) 6.0 (0.7) 5.0 (0.8) 6.0 (0.9) 5.5 (1.3) 6.3 (1.1) 5.9 (1.1) 2.5 (1.9) 2.4 (2.7) 6.0 (1.2) 5.8 (0.9) 5.9 (1.0) 93.0 (12.4) 104.1 (11.7) 81.4 (7.5) 77.0 (25.0) 285.4 (102.0) 288.4 (105.3) 6.4 (1.3) 5.7 (1.6) 6.0 (1.4) 93.2 (9.6) 109.7 (12.5) 78.4 (7.0) 70.9 (14.8) 286.3 (104.0) 292.6 (106.3) 0.3 (0.4) 0.6 (0.6) 0.7 (0.7) 0.2 (0.4) 0.1 (0.2) 0.3 (0.5) 2.0 (1.5) 4.9 (3.4) 2.8 (3.1) 0.4 (0.5) 0.6 (0.6) 0.7 (0.5) 0.1 (0.2) 0 (0.0) 0.2 (0.5) 1.4 (1.3) 6.5 (3.9) 5.4 (4.2) FEV1, Forced expiratory volume in 1 second; FVC, forced vital capacity; FEF25-75, forced expiratory flow 25% to 75%; PEFR, peak expiratory flow rate. *Quality of life scores range from 1 (maximal impairment) to 7 (no impairment). treatment were used for the analyses. At no time were comparisons made between the active and sham treatment groups because of the high risk of committing type I and II errors. RESULTS The pilot study took place from May 1996 to August 1998. Flow of study participants is outlined in Fig 1. A total of 96 patients were screened by telephone, with 46 patients undergoing baseline evaluations. Of the 46 patients evaluated, 10 did not qualify for inclusion. Of these, 6 patients decided they could not commit the time and effort, 3 had intermittent asthma, and 1 had severe asthma. Thirty-six qualified patients were randomly assigned to treatment, 24 to the active SMT group and 12 to the sham SMT group. Two patients randomly assigned to the active SMT group dropped out of the study before starting treatment as a result of serious illness in the family. The 2 patients had clinical and demographic characteristics similar to the rest of the patients in that group. Most of the children were classified as having moderate persistent asthma. The active and sham groups were dissimilar at baseline, especially in terms of classification and patient-rated severity. No attempts were made to perform statistical comparisons between the 2 groups. The important demographic and clinical characteristics are summarized in Table 1. The patients in the active SMT group received a mean of 19.6 treatment sessions, and the patients in the sham SMT group received an average of 19.3 treatment sessions. At the end of the 12-week intervention phase, the active SMT group showed little or no change in objective lung function tests (Table 2) and patient- and parent-/guardianrated day and nighttime symptoms (Table 3). Table 4 illustrates the patient-, parent-/guardian-, and pulmonologistrated asthma improvement at 12 weeks. Of the patient-rated measures, a reduction of approximately 20% in β2-bronchodilator use was observed (P = .10). The quality of life scores improved 10% to 28% (P < .01), with the activity scale showing the most change. The severity rating showed a reduction of 39% (P < .001), and there was an overall improvement rating corresponding to 50% to 75%. The pulmonologist-rated improvement was small. Similarly, the improvements in parent-/guardianrated outcomes were mostly small and not statistically significant. The changes in patient-rated severity and patientrated improvement remained unchanged at 12-month posttreatment follow-up assessment. The belief that active treatment was given was similar in both groups. At the end of the treatment phase, 64% of the children and parents or guardians in the sham group and 73% of the children and parents or guardians in the active group guessed that they were allocated to the active treatment group (Table 5). Journal of Manipulative and Physiological Therapeutics Volume 24 • Number 6 • July/August 2001 Chronic Pediatric Asthma and Chiropractic Spinal Manipulation • Bronfort et al Table 2. Change in pulmonary lung function tests in active SMT group: week 12 values in percent of baseline values Parameter Morning PEFR Evening PEFR FEV1 FVC FEV1/FVC FEF25-75 Bronchial challenge test (hyper-responsiveness) FEV1 5 min after exercise FEV1 15 min after exercise FEF25-75 5 min after exercise FEF25-75 15 min after exercise Body plethysmography TGV RV TLC RAW GAW SGAW IgE n Mean % 19 19 22 18 22 22 98.8 101.7 105.7 104.3 99.9 107.6 94.4 to 103.3 94.8 to 108.5 102.4 to 109.0 101.6 to 107.1 97.2 to 102.7 98.2 to 116.9 95% CI 22 22 19 22 112.6 104.1 113.0 103.6 97.5 to 127.6 99.8 to 108.4 81.3 to 144.6 92.7 to 114.5 12 12 12 12 12 12 15 101.9 96.1 100.6 86.8 162.7 137.4 109.6 92.7 to 111.0 74.5 to 117.7 95.2 to 106.1 58.6 to 115.0 86.0 to 239.4 95.5 to 179.2 70.4 to 148.8 PEFR, Peak expiratory flow reading; TGV, thoracic gas volume; RV, residual volume; TLC, total lung capacity; RAW, airway resistance; GAW, airway conduction; SGAW, specific airway conduction; IgE, immune-gammaglobulin E; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 second; FVC, forced vital capacity; FEF25-75, forced expiratory flow 25% to 75%. DISCUSSION The Medical Expenditure Panel Survey estimated that almost 7% of the United States population sought unconventional health care in addition to conventional medical care in 1996.5 The most common of the unconventional therapies was chiropractic care. Parents frequently seek care for their asthmatic children from chiropractors; however, there has been little scientific evidence to support such practices. Our study was an initial step in evaluating the scientific evidence of chiropractic spinal manipulation for children with asthma. We considered it important to perform a pilot study combined with a prospective case series before embarking on a full-scale trial. First, if clinically important changes were not observed prospectively in either lung function, asthma severity, day and nighttime symptoms, or asthma specific quality of life, we had decided a priori not to conduct a full-scale clinical trial with this study design. Second, we believed it was necessary to determine the study feasibility before undertaking a costly and timeconsuming full-scale, randomized clinical trial. Could patients be recruited in sufficient numbers to ensure adequate statistical power? What were the most cost-efficient methods of recruitment? Would patients and providers comply with study protocols? Could a sham SMT procedure be effectively delivered? We did establish that it is feasible to conduct a full-scale trial, although recruitment was slow and difficult. Patients and providers complied well with our protocols, and it appeared that patients and guardians were successfully blinded to the chiropractic treatment and had similar experiences of overall satisfaction regardless of group allocation. The prospective case series part of this study demonstrated that after 12 weeks of SMT combined with optimal medical management, there were no clinically important changes in pulmonary lung function (PEFRs, FEV1, forced Fig 1. Flow of participants. expiratory flow 25% to 75%, and hyperresponsiveness), patient-rated day and nighttime symptoms, and parent-/ guardian-rated assessment of the child’s quality of life and asthma severity. However, clinically important changes were found in patient-rated quality of life (particularly the activity domain) and patient-rated asthma severity and improvement. The discrepancy between child and parent/guardian ratings is consistent with those reported by other investigators.22 A study of similar design with a larger sample size was recently reported by Balon et al.23 When we compare our 373 374 Journal of Manipulative and Physiological Therapeutics Volume 24 • Number 6 • July/August 2001 Chronic Pediatric Asthma and Chiropractic Spinal Manipulation • Bronfort et al Table 3. Patient- and parent-/guardian-rated outcomes at week 12 in active SMT group: change from baseline Parameter Patient-rated Severity (0-10) Quality of life Symptoms Activity Emotions Overall score Diary scores (0-4) Wheezing Shortness of breath Coughing Disturbed sleep Feeling of panic Restricted activity β2-agonist use (no. of puffs/day) Parent-/guardian-rated Severity (0-10) Quality of life Activity Emotions Overall score Table 4. Patient-, parent-/guardian-, and pulmonologist-rated improvement in asthma at week 12 in active SMT group (n = 22) Improvement in asthma (1-9)* Patient-related Parent-/guardian-rated Pulmonologist-related Mean 95% CI 2.5 3.0 4.3 2.0 to 2.9 2.6 to 3.5 3.8 to 4.9 *1, No symptoms; 2, much better; 3, somewhat better; 4, a little better; 5, no change; 6, a little worse; 7, somewhat worse; 8, much worse; 9, twice as bad. results with the Balon et al trial, we note that similar and clinically important changes in asthma-specific quality of life and severity were found in both studies in the active SMT groups. However, the Balon et al study showed that these changes occurred in the sham SMT group as well. Although the improvements tended to be greater in the active group in most of the quality of life domains, they found no clinically important or statistically significant differences between active and sham SMT. There were no clinically important changes in lung function and airway hyperresponsiveness in either study. Patients in both studies had either chronic mild or moderate persistent asthma, but because they were optimally medically managed, their asthma was “under control.” In terms of lung function, there was therefore not much room for improvement, although we would expect a reduction in β2-agonist use to accompany any reduction in patient-rated asthma severity. There was also a similar decline in β2-agonist use in both studies. Again, this reduction in the Balon et al23 study was of equal magnitude in both the active and the sham SMT groups. What then are likely explanations for the patient-rated improvements in quality of life and patient-rated asthma severity? Recent research has shown that physical treatments such as massage appear to be beneficial in the management of children with pulmonary dysfunction and chronic asthma.24 An RCT by Field et al25 found that children n Week 12 (change from baseline) 95% CI 20 –1.4 –2.0 to -0.8 22 22 22 22 0.6 1.3 0.5 0.8 0.3 to 0.9 0.8 to 1.8 0.2 to 0.8 0.5 to 1.1 17 17 17 17 17 17 17 0.1 0 –0.1 –0.1 0 –0.1 –0.5 –0.1 to 0.3 –0.2 to 0.2 –0.5 to 0.4 –0.3 to 0.2 –0.1 to 0.1 –0.2 to 0.1 –1.5 to 0.4 22 –0.1 –1.2 to 0.9 22 22 22 0.6 0.4 0.5 0 to 1.2 0 to 0.8 0.1 to 0.9 who received 1 month of daily massage therapy by their parents showed decreased behavioral anxiety and increased cortisol levels. Thus it is possible that the physical contact involved in the spinal manipulation and the accompanying soft tissue palpation and massage used in the chiropractic studies may explain some of the benefits observed in our study. Patient education is another important part of the successful management of asthma. It is important for patients to understand their asthma, recognize its triggers, and learn to practice necessary management skills. Family support is essential in their efforts. It has been shown that patients and parents/guardians are better able to focus on clinicians’ recommendations after major concerns and fears have been addressed.26,27 Sometimes psychosocial dysfunction in the family may have a negative impact on the child with asthma.27,28 A recent systematic review concluded that family therapy for pediatric asthma appeared to reduce the severity of asthma and improve lung function, and it may be a useful adjunct to medication therapy.29 In our study, a substantial amount of time was spent educating parents and children on how to recognize and rate their asthma symptoms and how to perform peak flow measurements, assess readings, and use β2-agonists appropriately. The increased sense of control and knowledge about the asthmatic condition is likely to have resulted in anxiety reduction, contributed to proper medication use, and thus may also explain some of the observed improvement in outcomes. The daily use of asthma diaries might in itself account for improvement in both the active and sham SMT groups. A recent randomized trial showed that by having asthma patients write about stressful life events, pulmonary lung function was increased. 30 It is possible that by having patients in our study subjectively evaluate and rate their asthma symptoms, this expression of their asthma-related stressful events resulted in increased asthma-related quality of life. Journal of Manipulative and Physiological Therapeutics Volume 24 • Number 6 • July/August 2001 Chronic Pediatric Asthma and Chiropractic Spinal Manipulation • Bronfort et al Table 5. Assessment of treatment blinding Treatment assessment Correctly guessed treatment allocation at week 12 Incorrectly guessed treatment allocation at week 12 Overall patient/parent/guardian satisfaction* Placebo treatment (n = 11) Chiropractic treatment (n = 22) 4 7 1.0 (0.0) 16 6 1.4 (0.9) 1, Excellent; 2, very good; 3, good; 4, fair; 5, poor. *Means and SD. The frequency of care and the subsequent social connection that likely developed between the chiropractor and patients also deserves comment. Several studies have indicated that increased socialization is associated with positive health outcomes,31 and this too may account for some of the improvements noted in this study. Overall, our study corroborates the findings of the Balon et al23 and Nielsen et al18 studies; collectively, the studies suggest that factors other than the specific effects of SMT are contributing to most of the changes in quality of life and patient-rated asthma severity and improvement observed in these studies. If these factors are mainly nonspecific or placebo effects, what does this mean to patients, clinicians, and policy makers in considering the use of chiropractic care in the management of asthma? The placebo or nonspecific treatment effect has traditionally been regarded as a confounding or nuisance factor to be controlled for or eliminated. However, this nonspecific effect is an important and often powerful aspect of any therapy,32 and depending on the patient’s experience with the therapeutic encounter, it may potentiate the patient’s own healing capacity to different degrees. There is some evidence to suggest that this effect may be mediated by the brain through neural endocrine influences capable of modulating the function of the immune system.33 The theory that the brain is capable of influencing the immune system has been confirmed in several RCTs, which used interventions such as suggestion, self-hypnosis, imagery, and relaxation techniques.34 The nonspecific therapeutic effect has several known and likely several unrecognized dimensions. In the context of a clinical trial, the manner in which the informed consent is given, the expectations of the patient, and the enthusiasm and the attention of the treatment provider are factors that can have an impact on the patient-experienced outcome. It has been shown in practice-based studies that the doctor’s attitude toward therapy, whether positive or negative and either with or without confidence, has an influence on the outcome of treatment.35 It has been argued that it is unreasonable to discard a therapy or consider it worthless if it is only a little better or even no better than a suitable placebo. What matters is the magnitude of effect on patients’ outcomes when compared with commonly used treatments and in particular, no-treatment controls, if a patient wishes to decide more rationally which interventions a health care service should pay for.36 Two placebo-controlled trials examining the effect of adding chi- ropractic spinal manipulation to the optimal medical management of chronic asthma in either children or adults showed no important difference between the active and placebo arms.18,23 However, in both trials a clinically important improvement in asthma-related quality of life and a reduction in patient-reported asthma severity appeared to result in both active and sham SMT groups. These improvements are unlikely to occur solely as a result of the natural history or regression to the mean. On that basis, it may not be appropriate to deem the addition of chiropractic care to medical management worthless and to proscribe its use. Limitations When interpreting the findings of our prospective clinical series, it is impossible to make any causal inferences. The improvements observed in patient-oriented outcomes may be the result of a multitude of factors. Considering the chronicity of the disorder, the changes were unlikely the result of natural history. Some of the changes may be explained by regression to the mean because patients often enroll in studies when their symptoms are most severe. However, in this study patients went through a 2-month baseline period during which time their medical management was optimized. Changes in outcomes were measured from the end of this baseline period. In addition, it is possible that the specific effect of spinal manipulation may have been masked by the effect of the medications. Ethical considerations prevent the assessment of spinal manipulation alone in mild to moderate asthmatics. However, it is possible to design a study in which patients are given spinal manipulation in addition to medication and then monitored to see if medications can be reduced. According to the most recent guidelines, such a “step down” in medication should not be considered until the asthmatic condition has remained stable and has improved for at least 3 months. Thus for this to be assessed adequately, patients should be managed for longer periods to see if the reduction in medications can occur and if so, be maintained. Another consideration is that during the study period, almost half the children had upper respiratory infections. These children had substantially poorer outcomes compared with the children who did not have upper respiratory infections. Upper respiratory infections are extremely common in children with asthma and tend to mask improvement from ongoing therapy. Finally, it is possible that the SMT may 375 376 Journal of Manipulative and Physiological Therapeutics Volume 24 • Number 6 • July/August 2001 Chronic Pediatric Asthma and Chiropractic Spinal Manipulation • Bronfort et al have specific effects in only certain subgroups of patients, which we were unable to identify in our study given the relatively small sample. Future Research One of the strengths of this study is that it reflects to a certain extent what is occurring in health care today. Substantial numbers of patients are seeking “unconventional” health care in addition to medical care rather than as a replacement for it.5 Future studies should continue to assess the multidisciplinary comanagement of asthma to enhance study generalizability and even more importantly, to optimize patient care. We submit that future studies should focus their attention on assessing what aspects of the chiropractic clinical encounter are responsible for the improvement in important patient-rated outcomes observed in the studies performed to date. Is it the touch and attention? Is it the relaxation that may ensue from the physical nature of the chiropractic interventions? Maybe it is the filling out of diaries, the continuous monitoring, or increased patient focus on their condition, resulting in a better compliance, decreased anxiety, and appropriate use of prophylactic and abortive medications. It is possible still even in the light of the current scientific evidence that spinal manipulation does have worthwhile specific effects in certain patient populations. Likely, it is a combination of some or all of these factors. In any case, something is occurring that makes the patients feel better, as indicated by changes in well-recognized measures of quality of life.19 For this reason alone, future exploration is warranted. In addition, studies with larger sample sizes will be necessary to identify if worthwhile specific effects can be demonstrated in subgroups of patients. The personal dimension of the clinical encounter offers a rich potential for useful interventions.37 The generic elements of empathy and verbal and nonverbal communication (including listening and touch) need to be explored. The complexity of the physical, psychologic, and sociologic components of the chiropractic clinical encounter must be acknowledged, and it is likely that new methods for assessing these complex effects will need to be developed.37 CONCLUSION After 3 months of combining chiropractic SMT with optimal medical management for pediatric asthma, the children rated their quality of life substantially higher and their asthma severity substantially lower. These improvements were maintained at the 1-year follow-up assessment. There were no important changes in lung function or hyperresponsiveness at any time. The observed improvements are unlikely to be the result of the specific effects of chiropractic SMT, but other aspects of the clinical encounter that should not be readily dismissed. Further research is needed to assess which components of the chiropractic encounter are responsible for important improvements in patient-oriented outcomes so that they may be incorporated into the care of all asthmatic patients. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS We thank Jennifer Hart for assistance with manuscript preparation and the staff of the Wolfe-Harris Center for Clinical Studies and Children’s Health Care for their assistance with evaluation and treatment appointments. Finally, we thank the children and their guardians for devoting their time to this project and teaching us more about pediatric asthma. REFERENCES 1. Gergen PJ, Weiss KB. Changing patterns of asthma hospitalization among children: 1979 to 1987. JAMA 1990;264:1688-92. 2. Clark NM, Brown RW, Parker E, Robins TG, Remick DG Jr, Philbert MA, et al. Childhood asthma. Environ Health Perspect 1999;107(Suppl):421-9. 3. NIH. Expert panel report 2: guidelines for the diagnosis and management of asthma. NIH Publication; 1997. 4. Sears MR, Taylor DR, Print CG, Lake DC, Li QQ, Flannery EM, et al. Regular inhaled beta-agonist treatment in bronchial asthma. Lancet 1990;336:1391-6. 5. Druss BG, Rosenheck RA. Association between use of unconventional therapies and conventional medical services. JAMA 1999;282:651-5. 6. Lane DJ, Lane TV. Alternative and complementary medicine for asthma. Thorax 1991;46:787-97. 7. Lane DJ. What can alternative medicine offer for the treatment of asthma? J Asthma 1994;31:153-60. 8. Williams M. Complementary therapies for asthma. Community Nurs 1997;3:20-2. 9. Andrews L, Lokuge S, Sawyer M, Lillywhite L, Kennedy D, Martin J. The use of alternative therapies by children with asthma: a brief report. J Paediatr Child Health 1998;34:131-4. 10. Vange B. Kronisk syge smaborns kontakt til det autoriserede og det alternative behandlingssystem. Ugeskr Laeger 1989; 151:1815-8. 11. Beyeler W. Experiences in the management of asthma. Ann Swiss Chiro Assoc 1965;3:111-7. 12. Goldman SR. A structural approach to bronchial asthma. ACA J Chiro 1969;6:s81-4. 13. Masarsky CS, Weber M. Chiropractic management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Manipulative Physiol Ther 1988;11:505-10. 14. Nilsson N, Christiansen B. Prognostic factors in bronchial asthma in chiropractic practice. J Aust Chiro Assoc 1988; 18:85-7. 15. Miller WD. Treatment of visceral disorders by manipulative therapy. Bethesda (MD): US Department of Health, Education and Welfare; 1975. p. 295-301. 16. Hviid C. A comparison of the effect of chiropractic treatment on respiratory function in patients with respiratory distress symptoms and patients without. Bull Euro Chiro Union 1978;26:17-34. 17. Jamison JR, Leskovec K, Lepore S, Hannan P. Asthma in a chiropractic clinic: a pilot study. J Aust Chiro Assoc 1986;16: 137-43. 18. Nielsen NH, Bronfort G, Bendix T, Madsen F, Weeke B. Chronic asthma and chiropractic spinal manipulation: a randomized clinical trial. Clin Exp Allergy 1995;25:80-8. 19. Juniper EF, Guyatt GH, Feeny DH, Ferrie PJ, Griffith LE, Townsend M. Measuring quality of life in the parents of children with asthma. Qual Life Res 1996;5:27-34. 20. Juniper EF, Guyatt GH, Feeny DH, Ferrie PJ, Griffith LE, Townsend M. Measuring quality of life in children with asthma. Qual Life Res 1996;5:35-46. 21. Jaeschke R, Singer J, Guyatt GH. A comparison of seven-point and visual analogue scales. Data from a randomized trial. Control Clin Trials 1990;11:43-51. Journal of Manipulative and Physiological Therapeutics Volume 24 • Number 6 • July/August 2001 Chronic Pediatric Asthma and Chiropractic Spinal Manipulation • Bronfort et al 22. Guyatt GH, Juniper EF, Griffith LE, Feeny DH, Ferrie PJ. Children and adult perceptions of childhood asthma. Pediatrics 1997;99:165-8. 23. Balon J, Aker PD, Crowther ER, Danielson C, Cox PG, O’Shaughnessy D, et al. A comparison of active and simulated chiropractic manipulation as adjunctive treatment for childhood asthma. N Engl J Med 1998;339:1013-20. 24. Hernandez-Reif M, Field T, Krasnegor J, Martinez E, Schwartzman M, Mavunda K. Children with cystic fibrosis benefit from massage therapy. J Pediatr Psychol 1999;24:175-81. 25. Field T, Henteleff T, Hernandez-Reif M, Martinez E, Mavunda K, Kuhn C, et al. Children with asthma have improved pulmonary functions after massage therapy. J Pediatr 1998;132: 854-8. 26. Deaves DM. An assessment of the value of health education in the prevention of childhood asthma. J Adv Nurs 1993;18:354-63. 27. Gustafsson PA, Kjellman NIM, Cederblad M. Family therapy in the treatment of severe childhood asthma. J Psychosom Res 1986;30:369-74. 28. Lask B, Mathew D. Childhood asthma. A controlled trial of family psychotherapy. Arch Dis Child 1979;54:116-9. 29. Panton J, Barley EA. Family therapy for asthma in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2000; (2): CD 0089. Review. 30. Smyth JM, Stone AA, Hurewitz A, Kaell A. Effects of writing about stressful experiences on symptom reduction in patients with asthma or rheumatoid arthritis. A randomized trial. JAMA 1999;281:1304-9. 31. Spiegel D. Healing words: emotional expression and disease outcome. JAMA 1999;281:1328-9. 32. Kaptchuk TJ. Powerful placebo: the dark side of the randomised controlled trial. Lancet 1998;351:1722-5. 33. Solomon GF. Psychoneuroimmunology: interactions between central nervous system and immune system. J Neurosci Res 1987;18:1-9. 34. Vollhardt LT. Psychoneuroimmunology: a literature review. Am J Orthopsychiatry 1991;61:35-47. 35. Thomas KB. General practice consultations: is there any point in being positive? Br Med J Clin Res Ed 1987;294:1200-2. 36. Gotzsche PC. Is there logic in the placebo? Lancet 1994;344: 925-6. 37. van Weel C, Knottnerus JA. Evidence-based interventions and comprehensive treatment. Lancet 1999;353:916-8. CORRECTION In a correction listed on page 355 of the June 2001 issue, an author’s name was misspelled. The correct title and authors should read as follows: “Prognostic Values of Physical Examination Findings in Patients with Chronic Low Back Pain Treated Conservatively: A Systematic Literature Review” by Borge JA, Leboeuf-Yde C, and Lothe J (2001;24:292-5). We apologize for the error and regret any confusion it may have caused. 377