EBRD Strategy for Egypt: Private Sector, Utilities, Green Economy

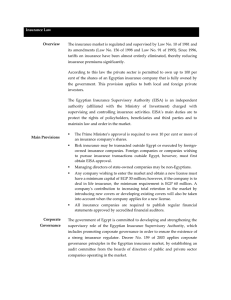

advertisement