Women's Labor in Jordan: Refugee & Jordanian Participation

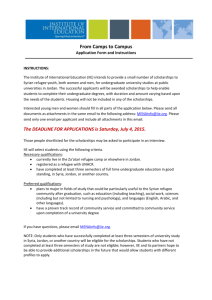

advertisement