Wiccatru, Folk Magic, and Neo-Shamanism Reconstructing mysticism in Nordic pagan traditions

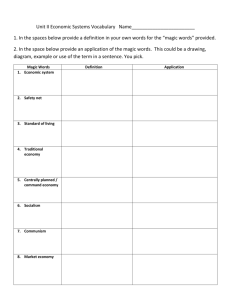

advertisement

Wiccatru, Folk Magic, and Neo-Shamanism Reconstructing the historical roots of magic and mysticism in Nordic pagan traditions Abstract: I originally set out to explore the historical precedent for folk magic, shamanic practice, and mysticism in a Heathen context. The impetus for this research grew out of debates in modern-day Heathenry regarding the validity of including magical and mystical elements in a reconstruction of Heathen praxis and worldview. Reconstructionist methods seek to provide both a historical foundation and an inspiration for modern Heathen practice, yet many lay researchers and practitioners overlook, disregard, or are simply unaware of historical precedents for these elements in Heathen practice. A common pejorative leveled at heathens who seek to include folk magic, ritual formulae, or direct contact with deities in their practice of Asatru or Heathen faith is “Wiccatru”: that the inclusion of such elements derives primarily from modern 19th- and 20th-century British and American Wicca, and therefore that some, most, or even all practices involving folk magic and mystical experience are invalid as reconstructionist practices. Furthermore, this paper steps back to examine why modern practitioners or would-be adherents of Heathenry are drawn to incorporate such elements in the first place. Methodologically, this paper draws together common threads from existing scholarly works to connect and explain in accessible terms common elements between historical practice and modern derivations of folk magic and mysticism in Heathenry, and their relationship to such practices as Wicca and Neo-Shamanism. Finally, it offers recommendations towards an integrative approach for those seeking to more accurately reconstruct and revive traditional Heathen magical or mystical practice for themselves and their communities. Brief Bio: Dara Grey began exploring new religious and mystical pathways at an early age and found a home in Heathenry at the beginning of 2009 with Diana Paxson’s Hrafnar kindred based out of Berkeley, California. She continues to research and explore the faith through building inclusive Heathen community, diving deeper into literary and scholarly sources, and engaging in personal devotional practice in her new home of Portland Oregon. ======================================================================== This paper arose from debates in online forums devoted to Heathen/Asatru cultural and spiritual debate over the past decade. From these scattered (and often heated) discussions, my research to create this specific paper has generated a volume of research on pertinent topics for the modern evolution of Heathen religion -- much broader than the initial scope. My purpose here is to refute two endlessly repeated talking points: The first, that magical, or mystical, or shamanic practices played no legitimate role in the day to day life of everyday people in pre-Christian pagan Northern Europe. Secondly that these practices and beliefs play no legitimate role in modern “reconstructionist” practice of Northern European paganism, popularly termed “Heathenry” and which encompasses a broad range of styles in neo-pagan religious practices, such as Asatru, Forn Sidr or Forn Sed, Theodism, Odinism, etc. In both research and writing, I’ve ranged far beyond strictly or exclusively Northern European studies into arenas of general analysis of culture, modernity, and religion, spiritual practices, and shamanism. This provides broader perspective that is often overlooked with focusing so narrowly on Northern European archaeology or historical anthropology, and which I believe informs a more holistic perspective on some of the areas of such concern in Heathenry today. The title word of this piece, “Wiccatru,” is included specifically to break down what exactly its users mean by the term, and further, to distinguish between Wiccan or generic neo-pagan ritual and magical practices and those which stem from Germanic and/or Nordic roots. Finally, by synthesizing evidence of historical Germanic mystic tradition and shamanic practice and comparing these elements with what is commonly incorporated from Wicca, this paper intends to set forth ideas for further reconstructing and reviving Germanic pagan practice as a living tradition. Before I break down these elements, I wish to discuss the limitations inherent in my research. I worked under several limits; the first is that I am an amateur scholar, and without any fluency in the mother languages of Northern Europe, I was unable to access many of the source materials directly. My research therefore depends, with gratitude, on the secondary analysis of the works of a number of actual scholars, whose works are credited with thanks in the bibliography. The second limitation was simply time. I first conceived of writing this paper in October of 2017, and the deadline for submitting and presenting it was this July. The more I looked for source material, the more tantalizing were the trails and source materials I found. Many scholars attempting a work of such depth and breadth might take many years to write, review, and finalize a paper or publication; and I have been humbled by the limits of available time and my own endurance in how much I could accomplish. Therefore, I invite readers to view this as nothing more than what it is: an initial review of secondary and where possible primary source materials, limited by time and scope and shaped with particular aims in mind. Fortunately, I did not have to search in vain nor was there any need to selectively ignore evidence contrary to my purpose; much well-researched and well-informed material was readily found in scholarly contexts. This paper attempts simply to synthesize and streamline this scholarly material, drawn both from the usually-suspected time frames and cultures, as well as from related disciplines of religious and cultural anthropology not directly related to either Heathen or Wiccan practice, and make it accessible in plain language for a broader audience. If you would know more, or what, I welcome investigation of my source materials directly. In initial explorations to uncover what exactly was meant by “Wiccatru” and what was or wasn’t Germanic or Nordic in origin, I found myself falling back on larger questions. As Wicca is primarily known as a system of magic or magical practice in common sense terms, I had to ask, what, exactly, is magic? How is magic different from religion? If a ritual is performed, what makes it a religious ritual rather than a magical one? The boundaries seem very clear according to the understandings laid out by Emile Durkheim, James Frazer, Rodney Stark, Charles Glock, and William Bainbridge, but in actual practice, and in examining the corpus of material having to do with Northern European paganism specifically, the boundaries are still much fuzzier than suggested by abstract semantic gymnastics. Referencing Stark and Glock’s studies, they identified and then further refined five distinct key dimensions of religion: 1. Belief: the expectation that the religious person will accept certain doctrines as true. 2. Practice: acts of worship and devotion directed toward the supernatural. Two important subtypes: a. Ritual: formal ceremonies, rites, and sacred activities (communal). b. Devotional: informal, often spontaneous, and frequently done in private. 3. Experience: individual belief that they have achieved direct, subjective contact with the supernatural. 4. Knowledge: expectation that people will know and understand central elements of their religious culture. 5. Consequences: taboos or prohibitions and the consequences for violating them. Rules on how to behave this way and not that way. Stark and Glock’s further empirical research found that there is significant independence between these different dimensions of religious commitment, and that people who rank high on one are not necessarily highly ranked on another. Stark and Bainbridge further posit, citing Durkheim, that magic does not concern itself with the meaning of the universe, but only with the manipulation of the universe for specific goals. Frazer and Mauss (Marcel Mauss, the nephew and protege of Emile Durkheim) distinguished as well between religion and magic, that religion involves ‘a propitiation or conciliation of powers superior to man which are believed to direct and control the course of nature and human life,’ whereas magic, according to Stephen Wilson, is more a spiritual technology, ‘so long as the ritual or formula is correctly performed, the effects of magic are thought to be automatic.’ Further complicating the debate is the question of what exactly religion and magic are, and whether they are separate and distinct or on a continuum of vaguely defined spiritual or metaphysical experience? Wilson observes that collective rituals in pre-modern Europe did have a magical aspect to them, that magical behavior corresponds to social consensus and reflects a social need. Mary Douglas compares and evaluates religion and magic, generically supernatural beliefs, along different lines: those of holiness and pollution, advanced or primitive. After absolutely demolishing the fundamental proposition of separating sacred (religion) from profane (magical), she unifies the concepts on a continuum by examining them both through the lens of ritual as symbolic of social processes, and from which perspective, consistency in worldview represented by both religious belief and magical belief can be seen as obeying the same rules regarding purity and uncleanliness. Take, for example, the pre-modern European folk practice of circling fields with fire for apotropaic or cleansing purposes. These were incorporated by the Church very early on to replace the pagan cultic practices, by which we can take that the powers called on may have been Christ or the saints rather than pagan gods or land spirits, but the practice itself remained unchanged. Chanting prayers or litanies involves an aspect of propitiatory belief, that by such actions holy powers might be enjoined to deliver protection and blessings of fertility; yet in the element of implicit certainty that taking these actions each year at particular times and in particular ways was necessary to secure these blessings, we can see the definition of magical spiritual technology at play as well. In experiential practice we can draw no clear defining line to separate the two. Both religion and magic can be seen as aspects of handling or working with supernatural forces or greater powers - seeking to influence that which cannot be done or obtained or known by ordinary physical or social means by use of rituals, symbols, spoken or written words, charged with energy and intent. Ritual can call on deities for specific purposes in a personal context (blessings for strength in battle, protection in battle, thanks for good harvest - either in advance or after the fact); rituals can be non-deity-focused but communal and have an intended magico-religious significance (jumping fires at Midsummer, staying up all night to tend the fire at Midwinter, walking the bounds of a field or ritual space with fire, placing tokens beneath stones or pillars at sacred sites, etc.). Rituals may be private affairs, too: setting out a bowl of milk or porridge for landwights (Jochens, Dowden); rune-risting (Havamal); making an offering at a spring or holy tree (Dowden); charging stones with energy; personal and private devotion to a deity or deities (Polome; Íslendingabók). The existence of shamanic practices, documented as such by both Mircea Eliade and Neil Price in the Northern European traditions, further complicates the picture and takes us into realms where again the boundaries between religious belief and magical practice blur. Eliade cogently observed in his seminal work on shamanism that: “In the archaic cultures communication between sky and earth is ordinarily used to send offerings to the celestial gods and not for a concrete and personal ascent; the latter remains the prerogative of shamans. Only they know how to make an ascent through the “central opening”; only they transform a cosmo-theological concept into a concrete mystical experience. This point is important. It explains the difference between, for example, the religious life of a North Asian people and the religious experience of its shamans; the latter is a personal and ecstatic experience. In other words, what for the rest of the community remains a cosmological ideogram, for the shamans (and heroes, etc.) becomes a mystical itinerary.” In his review of various cultural examples of shamanism, Eliade highlights the imagery in Norse mythology and the sagas of Northern Indo-European shamanic techniques: Odin’s role as seeker of knowledge, speaker with the dead, and rider of the tree; Yggdrasil as World Tree; journeying to the underworld; Utiseta or out-sitting, specifically at crossroads or on grave-mounds to gain supernatural knowledge, and Sleipnir as eight-footed shamanic steed, found by other names in other circum-polar shamanic traditions. Neil Price, in The Viking Way (2002), presents textual accounts of divinatory specialists associated with the Old Norse term seidr and correlates them with grave findings that suggest forms of shamanism, known collectively as seidr, were operational among Scandinavians during this period. While many prior analyses have treated the literary sources with caution as more or less fantastical and of doubtful use in determining actual ritual practices, Price’s archaeological surveys recover the historical basis, and finds that probable seidr practitioners were buried with ritual objects and apparent reverence that point to a role as valued religious specialists. Jennifer Snook’s work on modern American Heathenry highlights the ongoing tensions and debates around defining what exactly belongs in Heathen praxis which might count as a “valid” or “authentic” for Heathenry. Part of the difficulty in determining what exactly was believed or practiced in various contexts in pre-Christian Northern Europe lies in the efforts of Christian churchmen and the missionary kings to eradicate these very practices, in many cases by laying out legal prohibitions whose punishments could be quite severe (outlawry, dispossession, high fines, execution). Although excellent research has been done recently in merging the analysis of recent archaeological findings with perspective from historical anthropology, much is left to ontological indeterminacy: that the fundamental nature, or ontological status of the source of information cannot be decided definitely because the available information or observations can be interpreted in many ways, and there is therefore no absolute method to determine which interpretations may be best. Lastly, much of the modern research done to illuminate pre-Christian Northern European cultural practice and beliefs is highly academic and inaccessible to many Heathen or would-be Heathen practitioners, due to difficulty in locating the material itself, language barriers, heavily academic terminology and structure in the work, or the high cost to obtain copies of the research. All of this contributes to the tension and argument over what is authentically Heathen and what is not, with identity wars taking place over validity of practice. “Wiccatru”, as Snook observes and which my own surveys bear out, is taken to be largely pejorative, with implications of inauthenticity of practice, unnecessary high drama, cultural appropriation, lack of education, and a lack of care as to whether one’s practice actually fits within a Heathen framework or worldview. However, I found it useful to question why exactly might my co-religionists be drawn toward incorporating such elements into their practice in the first place? I posit here that the reasons are several-fold: that elements of Wicca speak to certain of the key aspects of religious life as defined by Stark and Glock in a way that the readily-available sources on pre-Christian Northern European practices do not; that Heathen adherents coming from Wicca are more accustomed to creativity in filling gaps in tradition with whatever feels most meaningful for them; that the sources which might fill those gaps more authentically are either practically inaccessible or entirely lost to time, and that all of these contribute to taking up elements which cannot be strictly traced back to Northern European practices. Ironically, what many pagans are doing today is more or less the same as what peasants were observed doing over centuries of recorded folklore: adapting bits and pieces of belief and practice from here and there, from this tradition or that framework as they deemed best, or as those pieces were regarded to be relevant and effective (Wilson). In trying to pin down what exactly goes into modern reconstructed (not borrowed!) Heathen praxis I found it useful to place what I personally know and have observed into a comparative matrix vis-a-vis Stark and Glock’s key elements of religion to see where any gaps might exist. Element of Religion Examples in modern Heathenry (with source, if available) Belief In general: - Existence of the Gods, Dwarves, Landvaettir, etc. Ancestor worship. Notable, however, that many modern Heathens have trouble taking the existence of any of these beings other than ancestors as literal. - Values as showcased by the Sagas (NNV is a common example, although many Heathens quibble over their accuracy or comprehensiveness) - Cosmology of Yggdrasil and the Nine Worlds (although again here as above, many regard this as mere metaphor) Practice: a) Rituals (communal, social) b) Devotionals (usually private) Rituals: - Blot (sacrifice - although many contestations over what is deemed an acceptable sacrifice) - Faining (blessing, often used with similar meaning to blot when there’s no blood sacrifice) - Sumbel/Symbel (passing a horn of drink ritually to recognize deities, ancestors/land spirits, and to toast or boast the living) - Seidr or Spae (prophesying or divining for the community in a public or semi-public context) Devotionals: - Private observances (adherents have no consensus on what these “should” look like or even whether they actually took place historically, although the story of Thorgeir Lawspeaker in Iceland’s conversion, and a few references from the sagas, Church writings, and early laws indicate they did exist. In modern practice, rune reading, rune galdr, meditations, offerings to house spirits, land spirits, deities) - Trance possessory events (uncommon in modern practice, usually not private but in small groups by invitation only) Experience Contentious! This ranges from claimed personal revelation from Northern European deities, landwights, alfar/disir to simply feeling a sense of connection with the divine in Heathen ritual as described above. Often, personal experiences are derided as “UPG” (Unverified Personal Gnosis) or the delusions of those who want to be “special” by Heathens who don’t feel connection or presence of any/all of these types of spiritual beings. Knowledge At a basic level: Eddas and Sagas, popular authors such as Paxson, Thorsson, et al. Intermediate: Old or public domain scholarship, lay scholarship such as published in Idunna or Odroerir or on private websites, familiarity with online “authorities” Advanced: modern academic scholarship, cross-disciplinary insights, deep knowledge across basic and intermediate sources Consequences Shunning or ostracization; subject of negative gossip; being labeled “fluffy”, “woo-woo”, “Wiccatru”, or similar; harsh criticism; “You’re doing it wrong!” Some elements of this matrix are more fully fleshed out than others. All this hints at, but leaves unanswered thus far why adherents or practitioners of Heathenry would incorporate elements from other traditions into their personal practice or group thew (“way”), having the benefit of a great deal of modern research and reflexivity at their disposal, unlike the common people of the past. Jennifer Snook’s research on American Heathenry, contrasted with Helen Berger’s research on Neopagans (specifically Wiccans), further joined with Mary Douglas’ studies and insights on purity and pollution and Anthony Giddens’ work on key aspects of modernity, provide us with some answers. In American Heathens, Snook addresses the anxiety and frustration felt by a number of her respondents in differentiating Heathenry from Wicca. She describes, often in the words of those interviewed, that Wicca is felt to be eclectic, loosely defined, untraditional, overly dramatic or overly involved in “high ritual,” “fluffy,” “woo-woo,” appropriative, based on “whatever feels good,” undisciplined, and so forth. Furthermore, at several points she returns to condensing the impression given by her respondents that all of these negative attributes are associated with femininity, liberal politics, and general flakiness. She further notes that authentic mystical practices ‘under the Heathen umbrella’ became viewed with suspicion due to the association of magic and mysticism with Wiccan, and “therefore feminine, liberal, and less authentic” influence. In complement to this, Berger’s study of neopagans, with an emphasis on Wiccans and practitioners of ceremonial magic, showcases these eclectic and arguably appropriative faith paths as creative, flexible, and re-inventive in ways which match the requirements of a disembedded, reflexive modern mindset. Giddens’ work, as considered here, is focused on the consequences of modernity in social relations, mind-set, economics, politics - the entire human sphere. Although he doesn’t specifically discuss religion in detail, his framework provides a means for understanding the vastly different ways which modern humans relate to their social, physical, and even interior mental environments. Key in his conceptual advances are reflexivity - the process of analyzing and reflecting on thought and action, even while undertaking either process - and disembedding, “the “lifting out” of social relations from local contexts of interaction and their restructuring across indefinite spans of time-space.” He further notes that while in pre-modern civilizations reflexivity is limited to interpreting and re-interpreting solely the traditions of the past, and evaluating all causes and events on this scale, in modernity reflexivity is constant and forces reevaluation on a daily basis, since routine no longer has any intrinsic connections with the past - that is, it is disembedded from a continuity or any traditional/constant context. Lastly, and most relevant to any discussion of reconstruction of Heathenry as a tradition, “ justified tradition is tradition in sham clothing and receives its identity only from the reflexivity of the modern.” There are two further salient points affecting, in general, the societal view in general of witchcraft: the first, as noted by Jenny Jochens, is that with the advent of Christianity, magic became unacceptable to the dominant religion. Scandinavian prohibitions against magic in law codes immediately follow prohibitions of sacrifices to or worship of Pagan gods. In examining folkloric sources, I myself observed how the tenor of reference to consulting the Sami, even the Sami themselves, moved from simple consultation of an expert in the field of spiritual intercession, to something forbidden and dangerous, such that by the time folktales are recorded from the early modern period, all “Finns” or “Lapps” (a somewhat derogatory term given by the Norwegians to the Sami) are referred to as cursed or damned beings who are born into pacts with the devil. Mary Douglas, after extensive review of many cultures’ views on witchcraft as a covert, harmful, or malign practice (or all three!), as opposed to the sanctioned and lawful, beneficial use of spiritual power, concludes that “Witchcraft, then, is found in the non-structure. Witches are social equivalents of beetles and spiders who live in the cracks of the walls and wainscoting. They attract the fears and dislikes which other ambiguities and contradictions attract in other thought structures, and the kind of powers attributed to them symbolize their ambiguous, inarticulate status.” Lastly, since much of the historical, textual and anthropological record of pre-Christian Northern European religious practice is lost, we will likely never know for certain what vardlokkur actually sounded like or contained; we may never know at all what forms of private practice Thorgeir Lawspeaker theoretically permitted the Icelandic people to practice in private; or any other number of things. It is into these gaps for which Wiccan, or other practices, appear to fill a need for various forms of self-fulfillment and religious expression. Douglas’ primary aim was to identify cultural practices in the context of religious or spiritual belief which spoke to holiness or acceptable practices and pollution. Situations in which social boundaries are unclear or unsettled, and in which there are no binding consequences for violating perceived boundaries, prompt pollution-rejection actions of various sorts (denouncement, shunning, even violence). The reactions of those using the term Wiccatru, and indeed the existence of the term itself as a pejorative, strongly indicate that Heathen communities are using it as a social tool to prevent pollution. Coupled with Snook’s observation that many Heathens self-identify as socially and culturally conservative (borne out in part by the results of the Worldwide Heathen Survey carried out in 2016 by Huginn’s Heathen Hof), this fundamental uncertainty around precise boundaries of the acceptable, along with a desire to be seen as masculine and good (and therefore accepted) rather than feminine and derided, may explain at least some of the anxiety around Wiccan themes or principles, in practice or in actuality, ‘tainting’ Heathenry. Interestingly enough, in this same vein although in a context far removed from modernity, is Jenny Jochens’ classifications of Norse women in textual evidence into four general types or roles: ● Warriors ● Prophetesses/Seeresses ● Avengers ● Whetters (Inciters) So although a significant traditional societal role appears to have been played by women with the power of prophecy or divining, many modern Heathens still reject these activities as not socially or communally acceptable. I surmise that the simple evidence of women as spiritually powerful and culturally regarded in historical practice may not be enough to overcome the simple psychological math that feminine = bad which is so prevalent in modern Western cultures. What are some of the differences, and what are some similarities between Wicca and reconstructed Heathen practice? Is there a way to tell any element of ritual or personal practice belongs to one and not the other? In an effort to separate the two, I’ve drawn up the following matrix, with the caution that this is not an exhaustive catalog of all traits of either path! Wiccan or Ceremonial Magic - - - - Generic or specific God and Goddess, but usually only one of each; distinct divinities are seen as aspects of generic God or Goddess and may be interchangeable in a given rite based on season, whimsy, etc. Core focus on magic, mystical thinking, and transformation of self Delineating ritual or sacred space by use of “calling the quarters” Emphasis on ritual as magical working (sometimes devoted to a specific material end, other times devoted to a deity or divine power) Specific mandatory ritual tools: cup, blade, wand, pentacle (cord, censer) Sharing of sanctified cakes and wine as ritual meal Ecstatic action to “raise energy” to define the circle Accepting of any and all pantheons and local terms for land spirits Degrees of initiation; clear hierarchy Play and creativity prized in developing new and interesting rituals and practices Each human as possessed of divinity Destiny can be known and controlled Northern European Pagan - - - - - Specific and distinct Gods and Goddesses; NOT interchangeable Distinct cosmological structure: Yggdrasil as World Tree or Axis Mundi; Nine Worlds as specific places Delineating ritual or sacred space by walking the bounds with fire, use of a cord and stakes, asperging with water or blood Belief that ritual serves community Use of mead, ale, honey water, switchel, etc. as ritual drink; usually passed around the circle in a horn Blades or other weapons traditionally forbidden in community ritual space (Concept of shared “luck” held by the horn) Acknowledgement and respect to ancestors as part of ritual practice Distinct terminology for “land spirits”: huldrefolk, landvaettir, alfar, tomte, etc. No initiatory rituals or passages needed to participate in or lead rituals Magic seen as traditionally a female practice (Destiny (wyrd, orlog, haminja) is inherited and/or set and can be - changed only by great effort, if at all) (Specific types of magic: galdr [magical songs], divination by runes, weather magic, drumming and/or singing to invoke trance and/or attention of non-human spiritual entities) Elements found in both realms Delineating ritual space in some way Divinatory practices Belief in sentient spiritual beings other than humankind Acknowledgement of, and respect for, spirits of the land Claiming the religion is based on ancient tradition Worldview and cosmological framework provides a basis for differentiating uniquely Heathen practice from those elements borrowed from other traditions. In advocating for a reconstructionist basis for revival or revitalization of historic seidr practices, I wish to emphasize clearly that this is not to be mistaken for advocating generic “neo-shamanic” practices. Neo-shamanism bears three key identifying characteristics, according to DuBois: a choice to follow a shamanic path; a focus on the individual j ourney rather than mediating the supernatural for a community; and a lack of shared cosmology o r framework. Granted, that in a religion mostly chosen by its adherents, having few generations born and raised to it, there will be modern seidr practitioners who feel they have chosen the path rather than the path having chosen them as in traditional societies. However, the performance of seidr for the Heathen community (either locally, or at large, or both) coupled with the cosmological framework of Yggdrasil and the Nine Worlds bind modern efforts at reconstructing Northern European shamanic practice within a more traditional framework generally and indeed, to a specifically Heathen worldview. Returning again to Eliade, Price, and Jochens, we see the following: ● ● ● Northern European pre-Christian cosmology still retains the essential framework of a specific, named cosmic World Tree (Yggdrasil), along with different levels or otherworldly arenas of existence (the nine worlds). Traditionally, women were seen as having natural or enhanced capabilities in the areas of vision and prophecy, and played roles from central to culture (community priestess, family priestess) to marginal (wandering seeress). Shamanic practices such as trance, singing, drumming, etc are documented from pre-Christian Northern European cultures in various ways from textual to archaeological. Therefore, I posit the following: ● That examination of the textual and archaeological records, while advancing steadily, is on one hand sufficient to provide an outline of culture and worldview, it is not exhaustive; ● That following only what is known for certain will allow for reconstruction of a limited folkway, but one with significant gaps in fulfilling living spiritual needs; ● But that taking up nearly-universal shamanic techniques again within the specific worldview and cosmology of pre-Christian Northern European paganism provides a potential path forward from this impasse while building upon an accepted, authentic, and culturally-specific cosmology. Thomas DuBois, in writing on shamanism and specifically tackling revival of nearly- or recently-extirpated shamanic traditions and indigenous religious practices, takes on a number of studies of tribes which have attempted a revival of lost or very nearly lost traditions. The two examples which hold the most similarity to some of the argumentation and disagreement in modern Heathenry are those of the Omaha and the Makaw. In the case of the Omaha, the leaders of the tribe made a decision to attempt repatriation of sacred objects passed to the National Museum of the American Indian. The leaders understood, however, that this was not without risk - since the relationship of the re-acquirers would be different from the accepted relationship of the prior keepers of these objects, they risked being blamed by the tribe for any impropriety or misfortune that might befall after reacquisition. DuBois observes, ‘the process of restoring an ancient ritual is no simple matter’ and that ‘the difficulties of striking a balance between according authority to (the sacred object) and assuming authority for one’s own culture lie at the heart of conflicts regarding repatriation.’ In the case of the Makaw, attempting to reestablish their sacred whale hunting rituals posed different difficulties. He cites loss of traditional knowledge caused by a gap of several generations between active practice and attempted revitalization, difference in opinion as to the moral acceptability and tribal necessity of reviving the hunt among both ecologically minded tribal activists as well as outside activists, and the unsettled tension between reviving traditional ceremonies within modern secular society. DuBois remarks that ‘these thorny issues seldom have simple answers and reflect ultimately the perplexing effects that colonial situations have wrought within many communities which once relied on shamanic rituals as keys to cosmic and social integration.’ While the majority of the successful revivals he showcases have fuller remnants of traditions, a major problem facing reconstructionists of pre-Christian Northern European traditions today is that instead of facing a gap of two or three or five generations, in most cases and for most customs Heathens today are looking at a gap of closer to thirty to fifty generations. DuBois further notes in his review of existing or current shamanic traditions, and various case studies in that context, that the success of any shaman’s career is dependent upon the approval and acceptance of their community. As his examples illustrate, even when a given person claimed to feel a shamanic call, if they were not approved by the community for any number of reasons (status, fit with traditional conceptions of who or how a shaman should be) then a prospective shaman was unlikely to succeed. All of which is to say that this effort will not come without controversy, difficulty, or community debate; and that those who attempt to assay this path will likely not meet with universal success and acceptance (as illustrated by Jenny Blain’s work on modern seidr practitioners). Indeed, I myself acknowledge that this debate may only work itself out organically on the timescale of generations, and that it will probably not be resolved within our lifetimes. However, I leave this discussion with the opinion that the effort is worthy, and will over the long term result in a stronger and more clearly-defined culture of distinctively Heathen spiritual practice. Gods willing it may endure. Bibliography: Berger, Helen A. A Community of Witches: Contemporary neo-paganism and witchcraft in the United States. University of South Carolina, 1999. Blain, Jenny. Nine Worlds of Seid-Magic: Ecstasy and neo-shamanism in North European paganism. Routledge, 2002. Chisholm, James and Flowers, Stephen E. A Source-Book of Seid. Lodestar Press, 2015. Davidson, Hilda Ellis. The Lost Beliefs of Northern Europe. Routledge, 1993. Douglas, Mary. Purity and Danger: an analysis of concepts of pollution and taboo. Praeger Publishers, 1966. DuBois, Thomas A. Nordic Religions in the Viking Age. University of Pennsylvania Press, 1999. DuBois, Thomas A. An Introduction to Shamanism. Cambridge University Press, 2009. Eliade, Mircea. Shamanism: Archaic Techniques of Ecstasy. Princeton University Press, 2004 ed. Farrar, Stewart. What witches do: a modern coven revealed. Phoenix Publishing, 1991. Gårdbäck, Johannes Björn. Trolldom: Spells and methods of the Norse folk magic tradition. 2nd ed., YIPPIE Press, 2017. Giddens, Anthony. The Consequences of Modernity. Stanford University Press, 1990. Grágás: Konungsbók. ed. by Vilhjálmur Finsen, 1852. Odense University Press, 1974. Grattan, J. H. G., and Singer, Charles. Anglo-Saxon Magic and Medicine: Illustrated specially from the semi-pagan text “Lacnunga.” Oxford University Press, 1952. Hicks, Shane. ‘Cult and Identity in Modern Heathenry’ in Odroerir: The Heathen Journal, Vol. 2, August 2014. Hiebert, Paul G. Anthropological Insights for Missionaries. Baker Book House, 1985. Hutton, Ronald. The Triumph of the Moon: A history of modern pagan witchcraft. Oxford University Press, 1999. Jochens, Jenny. Old Norse Images of Women. University of Pennsylvania Press, 1996. Mitchell, Stephen A. Witchcraft and Magic in the Nordic Middle Ages. University of Pennsylvania Press, 2013. Online: “What is Wiccatru?” Asked in: Asatru Gathering: https://www.facebook.com/groups/AsatruCommunity/permalink/1362333203910297/ Asatru & Heathenry: https://www.facebook.com/groups/heathenry/permalink/10156345474657612/ Huginn’s Heathen Hof: https://www.facebook.com/groups/heathenhof/permalink/2086496751587603/ The Asatru Community: https://www.facebook.com/groups/thenewasatrucommunity/permalink/16745588726203 99/ The Troth: https://www.facebook.com/groups/TheTroth/permalink/1721723231254411/ Polome, Edgar C. “Indo-European Culture, with Special Attention to Religion,” in The Indo-Europeans in the Fourth and Third Millenia. Karoma Publishers, 1982. Price, Neil s. The Viking Way: religion and war in late Viking age Scandinavia. University of Uppsala, 2002. Raudvere, Catharina. ‘Trolldomr in Early Medieval Scandinavia’ in Witchcraft and Magic in Europe, Volume 3: The Middle Ages. The Athlone Press, 2001. Revelations of St. Birgitta of Sweden, The: Liber Caelestis, books VI-VII. Oxford University Press, 2012. Rood, Joshua. ‘Reconstructionism in Modern Heathenry’ in Odroerir: The Heathen Journal, Vol. 1, August 2014. Russell, James C. The Germanization of Early Medieval Christianity: A Sociohistorical Approach to Religious Transformation. Oxford University Press, 1996. Rustad, Mary S. The Black Books of Elvernum. Galde Press, 1999. Scandinavian Folk Belief and Legend. University of Minnesota Press, 1991. Snook, Jennifer. American Heathens. Temple University Press, 2015. Stark, Rodney and Bainbridge, William Sims. The Future of Religion. University of California Press, 1985. Walsh, Roger N. The Spirit of Shamanism. St. Martin’s Press, 1990. Wilson, Stephen. The Magical Universe: Everyday Ritual and Magic in Pre-Modern Europe, 2000. World Wide Heathenry: Huginn’s Heathen Hof 2016 Demographic Survey Findings. At http://www.heathenhof.com/world-wide-heathenry/ accessed July 2018.