cordier2010

advertisement

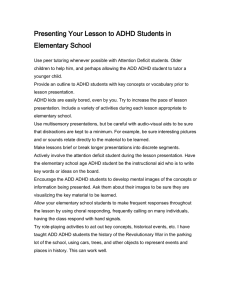

Australian Occupational Therapy Journal Australian Occupational Therapy Journal (2010) 57, 137–145 doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1630.2009.00821.x Research Article Comparison of the play of children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder by subtypes Reinie Cordier,1 Anita Bundy,1 Clare Hocking2 and Stewart Einfeld1,3 1Faculty of Health Sciences, The University of Sydney, Sydney, New South Wales, Australia, 2School of Rehabilitation and Occupation Studies, AUT University, Auckland, New Zealand, and 3Brain and Mind Research Institute, The University of Sydney, Sydney, New South Wales, Australia Background: Studies have found differences in the nature and severity of social problems experienced by children with different subtypes of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Given that play is often the context for acquiring social skills, there is surprisingly limited research examining whether these differences distinguish the play of children within the groups. Methods: Using the Test of Playfulness (ToP), we examined the similarities and differences in play between children (aged 5–11 years) diagnosed with the three DSM-IV ADHD subtypes: inattentive (I-subtype; n = 46), hyperactive-impulsive (HI-subtype; n = 28) and combined subtypes (C-subtype; n = 31). Results and conclusions: Bias interaction, an item-byitem analysis, revealed that the hierarchy of ToP items was similar for children with the HI- and C-subtypes, but differed for children with the I-subtype. Specifically, children with the I-subtype found it more difficult to become intensely engaged in play and to take on playful mischief and clowning; however, they found social play items to be easier. Conversely, whereas mischief and clowning were relatively easier for children with the HI- and C-subtypes, many items reflecting social interaction were more difficult. These findings suggest that interventions can be Reinie Cordier MOccTher; BSocSc Hons (Clin Psych). Anita Bundy ScD, OTR, FAOTA; Chair of Occupation and Leisure Sciences. Clare Hocking PhD, MHSc (OT); Associate Professor. Stewart Einfeld MD, DCH, FRANZCP; Chair of Mental Health, Faculty of Health Sciences & Senior Scientist, Brain and Mind Research Institute. Correspondence: Anita Bundy, Faculty of Health Sciences, The University of Sydney, P.O. Box 170, Lidcombe, Sydney, NSW 1825, Australia. Email: a.bundy@usyd.edu.au Accepted for publication 1 September 2009. 2010 The Authors C 2010 Australian Association of Journal compilation Occupational Therapists C tailored to these differing presentations. However, further research is needed to confirm the findings. KEY WORDS play, child development, paediatrics. Introduction Substantial research has shown differences between children representing the three attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) subtypes identified in the DSM-IV, namely predominantly inattentive (I-subtype), predominantly hyperactive-impulsive (HI-subtype) and combined (C-subtype) (American Psychiatric Association, 2000; Barkley, 2003). Children with the subtypes are reported to differ in their cognitive processes, psychosocial presentation, comorbid conditions and response to treatment (Barkley; Diamond, 2005). Although three subtypes have been distinguished, there is mounting belief that the HI- and C-subtypes are quite similar and that they differ substantially from the I-subtype (Diamond, 2005; Milich, Balentein & Lynham, 2001). Children with the HI- and C-subtypes are more likely to have the behaviours classically associated with ADHD. They tend to be distractible, have poorer persistence and have problems with planning and shifting between activities (i.e. transitioning). In contrast, children with the I-subtype are less distractible and tend to be more withdrawn (Milich et al., 2001). Also, children with the HI- or C-subtype tend to be more aggressive and impulsive (Carlson, Shin & Booth, 1999; Gaub & Carlson, 1997) and have greater externalising behaviours (Baeyens, Roeyers & Vande Walle, 2006; Carlson et al.), whereas children with the I-subtype tend to be socially passive (Barkley, 2003) and present with more internalising behaviours (Baeyens et al.; Carlson et al.). Unlike children with HI- or C-subtype, children with the I-subtype seem to lack motivation (Diamond, 2005). Perhaps unsurprisingly, children with the I-subtype are less likely than the others to develop oppositional defiant disorder (ODD) and conduct disorder (CD) (Baeyens et al.). 138 R. CORDIER ET AL. Given the well-documented differences among children with the varying ADHD subtypes, it is reasonable to suspect that their play patterns also will differ. However, there is surprisingly little published research on the impact of ADHD on play. The limited existing research on play and ADHD in general suggests that children with ADHD engage in less associative and cooperative play than typically developing peers (Alessandri, 1992). Leipold and Bundy (2000) found that children with ADHD are less playful. Alessandri found that children with ADHD struggle to transition between play activities. Melnick and Hinshaw (1996) established that children with ADHD demonstrate more negative behaviours in play (e.g. disruptions and rule violation). Cordier, Bundy, Hocking and Einfeld (forthcoming) observed that within the context of play, children with ADHD present with less interpersonal empathy. We are not aware of any studies that investigate similarities or differences in the play of children with different ADHD subtypes. This study is part of a larger investigation in which we compared the play of children with ADHD with that of children without ADHD. However, only the children with ADHD are discussed in this study. In this work, we examined whether the play of children with the three subtypes differed in ways that would be predicted by known differences in their cognitive processing, psychosocial abilities and tendency to develop comorbidities, as cited earlier. For the purposes of this study, play was defined as a transaction between the individual and the environment that is intrinsically motivated, internally controlled, free of many of the constraints of objective reality and framing-related skills (reading and responding to cues; Bateson, 1971, 1972; Skard & Bundy, 2008). Play manifests in children as playfulness (i.e. the disposition to play; Bundy, 2004; Neumann, 1971). Most authors have written about play and playfulness as though they are synonymous (Barnett, 1991; Skard & Bundy; Neumann). Using this definition and the Test of Playfulness (ToP), which operationalises the definition, we further explored if differing characteristics can be observed in the play of the ADHD subtypes. We tested the following hypotheses. Hypothesis 1: Item hierarchy (i.e. estimated item measure calibrations) will be the same for children with the HI- and C-subtypes. Hypothesis 2: Children with ADHD I-subtype will have lower estimated measure calibrations on ToP items that reflect intrinsic motivation (i.e. they will find those items harder) than is predicted by the Rasch model calculated on all subtypes. Hypothesis 3: Children with ADHD HI- and C-subtypes will have significantly lower estimated measure calibrations on ToP items that reflect social skill than is predicted by the Rasch model calculated on all subtypes. Hypothesis 4: Children with ADHD HI- and C-subtypes will have significantly higher estimated measure calibrations on ToP items that reflect mischief ⁄ teasing and clowning ⁄ joking (i.e. they will find those items easier) and children with the I-subtype will find the same items more difficult than is predicted by the Rasch model calculated on all subtypes. Methods Ethical approval was obtained from the University of Sydney Human Ethics Research Committee and the Northern Y Regional Ethics Committee, New Zealand. Participants Participants were children aged between 5 and 11 years who were diagnosed with ADHD (n = 105). The children were recruited from district health boards and paediatricians’ practices in Auckland, New Zealand. Diagnostic procedures were followed to ensure high levels of diagnostic accuracy and to minimise the inclusion of borderline cases (i.e. cases just failing to reach the criteria on the DSM-IV) and cases where diagnoses other than ADHD were deemed primary. As part of the diagnostic workup, participants went through an initial assessment. If ADHD was suspected, a Connors’ Parent Rating ScalesRevised (long version; CPRS-R: L) was administered. Furthermore, a school observation was conducted and a CTRS-R: L was administered. If the findings supported the diagnosis of ADHD, the child was referred to an ADHD subunit specialising in the diagnosis of ADHD. The psychiatrist ⁄ paediatrician then made the diagnosis of ADHD if the child met the DSM-IV criteria, including the ADHD subtype. Children were included if they had conditions commonly associated with ADHD, such as learning disorders, ODD, CD, anxiety disorder and mood disorder. They were excluded if they had other major neuro-developmental or psychiatric disorders, such as autistic spectrum disorders, intellectual disabilities, movement ⁄ tic disorders and organic brain syndromes. Additionally, any children with ADHD who were on medication, wherein an overnight period was insufficient for washout (e.g. atomoxetine), were excluded. After inclusion in the study, an additional CPRS-R: L was administered to confirm the diagnosis of ADHD. The CPRS-R: L has three DSM-IV scales that categorise the child with ADHD into the subtypes. The subtype was determined by the clinicians and checked against the CPRS-R: L subtype classification. The agreement between the clinician classification into the ADHD subtypes and the CPRS-R classification was 93.8%. There was discordance between the original subtype classification and the subtype determined by the CPRS-R: L screening for seven participants, who were then excluded from the study. The children with ADHD were finally allocated into the following three ADHD subtype categories: I-subtype (n = 46), HI-subtype (n = 28) and C-subtype (n = 31). Each child with ADHD invited a typically developing playmate (n = 105) to a play session; playmates were of a Journal compilation C C 2010 The Authors 2010 Australian Association of Occupational Therapists 139 ADHD SUBTYPES AND PLAY similar age to the children with ADHD and were familiar to them. For the purpose of this study, ‘typically developing playmate’ is defined as a child (i) who did not have ADHD (i.e. scored below the clinical cut-off for any of the CPRS-R subscales and DSM-IV scales) and (ii) for whom no concerns had been raised about development by a teacher or health professional. Overall, children who were not proficient in English were excluded because use of English is necessary for interpreting the ToP by an English-speaking rater. The mean ages of the respective groups were: I-subtype= 9.2; HI-subtype = 8.9; and C-subtype = 9.2. The remainder of demographic information for the participants and their primary caregivers is summarised in Table 1. To assist with interpretation of the ToP results, the mean CPRS-R: L subscale scores are summarised in Table 2. The children with ADHD and their playmates were not matched on any criteria as the playmates of children with ADHD were selected by the children with ADHD. This was carried out to ensure that an unfamiliar playmate would not influence the play situation, a factor overriding the potential benefit of matching participants within the ADHD group. Instruments The ToP (Bundy, 2004) was used to measure the children’s play. The ToP is a 29-item observer-rated instrument that can be administered to any individual between the ages of 6 months and 18 years. Each item is rated on a four-point (0–3) scale. Scores reflect extent (proportion of time), intensity (degree of presence) or skilfulness (ease of performance). The ToP measures the concept of playfulness as a reflection of the combined presence of four elements contributing to a single (unidimensional) construct of playfulness: perception of control, freedom from constraints of reality, source of motivation and ability to give and read social cues. Although the ToP was designed to represent a theoretical conceptualisation of playfulness comprised of multiple elements, playfulness is a single construct; thus, it is not feasible to analyse data by the four elements (Bundy). One overall score on the scale is calculated with a mean of 50 and a standard deviation (SD) of 10. The ToP is administered in an environment that is supportive of play and has evidence of excellent inter-rater reliability (data from 96% of raters fit the expectations of the Rasch model) and construct validity (data from 93% of items and 98% of people fit Rasch expectations; e.g. Bundy, Nelson, Metzger & Bingaman, 2001). The CPRS-R: L is a paper-and-pencil screening questionnaire completed by parents ⁄ primary caregivers to assist in determining whether children between the ages of 3 and 17 years have signs and symptoms consistent with the diagnosis of ADHD. The CPRS-R: L has evidence of excellent reliability (international consistency reliability 0.75–0.94) and construct validity (to discriminate ADHD from the non-clinical group: sensitivity 92%, specificity 91%, positive predictive power 94% and negative predictive power 92%) (Conners, 2004; Conners, Sitarenios, Parker & Epstein, 1998). Conners’ scales have been found to be effective in the differential diagnosis of children with the varying ADHD subtypes, with and without comorbid conditions, when used in combination with other data sources, such as a diagnostic interview (Hale, How, Dewitt & Coury, 2001). The primary purpose of using the CPRS-R: L was to screen children for inclusion into or exclusion from the study, and to assist in the interpretation of ToP findings. Procedure The environment from where the data were gathered was a playroom set up specifically for the assessment at a TABLE 1: Participant demographics ADHD participants I-subtype HI-subtype C-subtype ADHD subtype ratio Percentage boys Percentage girls Primary caregiver’s highest level of education Did not complete high school Completed high school Completed tertiary qualifications Primary caregiver’s occupation Jobs that do not require tertiary qualifications‡ Jobs that do require tertiary qualification 2 (n = 46)† 76.1 23.9 1 (n = 28)† 78.6 21.4 1 (n = 31)† 71.0 29.0 10.9 67.4 21.7 10.7 50.0 39.3 19.4 51.6 29.0 54.3 45.7 64.3 35.7 71.0 29.0 †The attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) subtype ratio is similar to the ratio reported in a recent national Australian representative sample (Graetz, Sawyer, Hazell, Arney & Baghurst, 2001). ‡Tertiary qualifications refer to qualifications obtained after school, that is, qualifications obtained from a college or a university. C-subtype, combined; HI-subtype, hyperactive-impulsive; I-subtype, inattentive. 2010 The Authors C 2010 Australian Association of Occupational Therapists Journal compilation C 140 R. CORDIER ET AL. TABLE 2: Connors’ Parent Rating Scale-Revised (CPRS-R) subscale scores I-subtype (n = 46) HI-subtype (n = 28) C-subtype (n = 31) Subscales Subscale description Mean SD Mean SD Mean SD F P Oppositional Break rules, problems with authority, easily annoyed Learn slowly, organisational problems difficulty completing tasks concentration problems. Have worries and ⁄ or fears, emotional, sensitive to criticism, shy, withdrawn Set high goals, fastidious, obsessive Have few friends, low self-esteem and self-confidence, feel emotionally distant from peers Report an unusual amount of aches and pains. Emotional, cry a lot, get angry easily Broad-ranged behaviour problems 65.7 12.8 68.4 10.7 79.5† 11.2 13.3 <0.001 73.3† 9.3 68.3 8.4 74.6† 12.9 3.1 0.053 57.3 13.6 53.8 10.4 65.2 11.3 7.0 0.001 53.9 71.3† 11.2 17.6 54.0 74.2† 10.3 10.1 60.2 85.2† 14.2 11.9 3.0 9.0 0.052 <0.001 68.2 18.2 54.3 14.2 66.7 17.4 6.4 0.002 60.6 67.3 13.5 10.2 56.6 71.2† 10.1 6.7 71.0† 83.7† 11.1 10.0 11.9 29.2 <0.001 <0.001 Cognitive ⁄ inattention problems Anxious ⁄ shy Perfectionism Social problems Psycho-somatic Emotional labile Behavioural problems †Denotes CPRS-R subscale mean scores above the clinical cut-off (i.e. behavioural problems are significant for the respective subscales). C-subtype, combined; HI-subtype, hyperactive-impulsive; I-subtype, inattentive; SD, standard deviation. clinical site where the children with ADHD came regularly for assessment or intervention. According to Bundy (2004), the environment should be one in which the child feels physically and emotionally safe to increase the chances for spontaneous and intrinsically motivated play to occur. The categories of the Test of Environmental Supportiveness (TOES) were used as a guideline for establishing play spaces with the maximum chance of promoting play. The TOES operationalises the ways in which the four aspects of the environment influence players’ motivation to play: playmates, objects, play space and the sensory environment (Skard & Bundy, 2008). The toy selection catered to likely motivations for engaging in free play arising from gender differences and age. A diversity of play materials was present in the room to support a range of play. The same toys were present during all play sessions and the children were allowed to choose play materials and activities. Approximately 60% of the playmates of children with ADHD were siblings because that proportion of the children with ADHD identified that they did not have another usual playmate. Parents ⁄ guardians were requested not to administer medication prescribed for ADHD on the day of the assessment as we were interested to observe how ADHD affects play without the effects of medication. The assessor tried to make the participants feel at ease prior to the interactive free play session. Each observation included approximately 20 minutes of playtime. An assessor was present in the playroom but was as unobtrusive as possible and had been instructed not to intervene unless a child was in danger. When children attempted to interact with the assessor, the assessor’s response was neutral. The entire interactive free play session was recorded on videotape by a handheld video camera for purposes of later scoring. A single experienced rater assessed all the children using the videotapes. Prior to scoring, the rater was calibrated on the ToP, which means the consistency of her ratings was compared with that of hundreds of other raters in a larger ToP sample (N > 3000 observations); her calibration results demonstrated that she is a reliable rater. To ensure that her scores did not drift, the rater rescored approximately 20% of the videotapes; these were randomly selected. Her data from both test administrations were analysed with Facets (see the following para); scores for each child were compared time 1 vs. time 2 and found to be equivalent because the overall scores for no child differed by more than the standard error of measurement. The rater did not participate in any other aspect of the study and was blinded to the purpose of the study to minimise bias. Data analysis To attain interval-level scores for each participant, the ToP raw scores were subjected to Rasch analysis using Journal compilation C C 2010 The Authors 2010 Australian Association of Occupational Therapists 141 ADHD SUBTYPES AND PLAY the Facets program (version 3.62.0; Linacre, 2007). The Rasch model enables the researcher to examine simultaneously (i) whether or not the items define a single unidimensional construct (playfulness in this instance); (ii) the relative difficulty of each test item; and (c) the relative playfulness of each person taking the test (Bond & Fox, 2007). In addition to estimates of the relative difficulty of items and ability of people, the Rasch analysis yields goodness-of-fit statistics expressed in MnSq and standardised values. Prior to further calculations, we examined the goodness-of-fit statistics for people and items to ensure that they were within an acceptable range set a priori (MnSq < 1.4; standardised value < 2; Bond & Fox, 2007); this ensured that the measured scores were true interval-level measures. Bias-interaction analysis, also called differential item functioning (DIF), generated by Facets, was used to examine whether the relative difficulty of the ToP items differed significantly for one or more of the three subgroups of children with ADHD (I-subtype vs. HI-subtype vs. Csubtype). DIF occurs when people from different groups with the same latent trait (in this case playfulness) have a different probability of giving a certain response on a questionnaire or test (Embretson & Reise, 2000). DIF analysis, expressed in t-values, provides an indication of how different the scores of the subgroups were on each item. An item displays statistically significant DIF when a t-value is ‡1.96, indicating that the difficulty level estimated by Facets for that item differed across groups (Wendt & Surges-Tatum, 2005). Because we hypothesised no more DIF in each of these items, considered one at a time, than could occur by accident, we considered each t-test to stand by itself. Thus, we did not apply Bonferroni (or other similar) adjustments (J. M. Linacre, personal communication, 17 June 2008). The significance level was set at P £ 0.05. The need for DIF was suggested by a pattern of unexpected ratings (i.e. scores that were unexpectedly low or high, given a child’s overall level of playfulness). These unexpected ratings were associated primarily with eight items reflecting intrinsic motivation, social skill or mischief ⁄ clowning. Of the 87 unexpected ratings awarded, 76 (87%) were associated with these items. DIF also can be used to ensure equivalence of the groups with respect to potentially confounding variables. We tested the effects of nine such variables: (i) gender, (ii) age (in three bands: 5–6, 7–8 and 9–11 years), (iii) ethnicity, (iv) socio-economic status, (v) younger vs. older sibling playmates, (vi) age difference between playmate pairs, (vii) sibling vs. non-sibling playmate pairs, (viii) clinically significant ODD symptoms vs. non-clinically significant ODD symptoms and (ix) clinically significant anxiety symptoms vs. non-clinically significant anxiety symptoms. None of the listed confounding variables was found to be significantly different between groups (P < 0.05). Results DIF analysis revealed no differences in item hierarchy for children with the HI- and C-subtypes. Thus, Hypothesis 1 was supported. As hypothesised, children with the I-subtype had significantly lower estimated measure calibrations than predicted by the Rasch model on one intrinsic motivation item: ‘intensity of engagement (22)’. Children with the I-subtype found this item to be much easier than had been predicted by the model calculated on all the subtypes. However, they did not find any other items reflecting intrinsic motivation to be easier than predicted. Thus, Hypothesis 2 was only partly supported. Also as hypothesised, children with the HI- and C-subtypes had estimated item calibrations that were significantly higher (easier) and children with the I-subtype had estimated item calibrations that were significantly lower (harder) than predicted on ‘mischief (17)’ and ‘clowning (19)’. Furthermore, children with the HI- and C-subtypes had estimated item calibrations that were significantly lower (harder) on five social skill items: ‘initiating play (1)’, ‘sharing (4)’, ‘supporting the play of others (5)’, ‘social play (12)’ and ‘responding to play cues (29)’. Thus, Hypotheses 3 and 4 were fully supported. The t-values generated by bias interaction to compare scores on each item for the children in the different subtypes with those expected by the Rasch model are provided in Table 3, together with their corresponding item descriptions. An item-by-item comparison of the subtypes is illustrated in Figure 1. In the remainder of the study, the ToP item numbers, as shown in Table 3, are used in brackets for reference. Discussion When we examined the play patterns of children representing the three ADHD subtypes, we found that they were very similar for children with the HI- and C-subtypes, supporting the mounting evidence for the case that they are overall alike. Children with the I-subtype differed in ways that would be predicted by known differences in cognitive processing, psycho-social ability and comorbidity. Furthermore, because none of the confounding variables that we tested accounted for the observed differences and because the rater was blind to the purpose of the study, the differences are very likely to be the result of actual differences among the subtypes. ‘Intensity of engagement (22)’, which measures the degree to which a player is concentrating on the activity and is thought to reflect intrinsic motivation, was significantly more difficult than predicted by the overall Rasch model for children with the I-subtype. Because the play situation was designed to be particularly appealing, these findings partially support Diamond’s (2005) hypothesis that the primary problem of children with the I-subtype is decreased motivation rather than inattention. 2010 The Authors C 2010 Australian Association of Occupational Therapists Journal compilation C 142 R. CORDIER ET AL. TABLE 3: Test of Playfulness item descriptions and t-values (for an indicator of differential item functioning) for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder subtypes t-value* Item Perception of control 1 – Skill of initiating play 2 – Skill of negotiating needs 3 – Extent of deciding what to do 4 – Skill of sharing ideas or objects 5 – Skill of supporting the play of others 6 – Intensity of interacting with objects 7 – Skill of interacting with objects 8 – Skill of modifying task requirements 9 – Skill of transitioning between activities 10 – Extent of playing with others 11 – Intensity of playing with others 12 – Skill of playing with others Freedom from constraints of reality 13 – Extent of pretending 14 – Skill of pretending 15 – Extent of using people ⁄ objects unconventionally 16 – Skill of using people ⁄ objects unconventionally 17 – Extent of using mischief ⁄ teasing 18 – Skill of using mischief ⁄ teasing 19 – Extent of using clowning ⁄ joking 20 – Skill of using clowning ⁄ joking Source of motivation 21 – Extent of being engaged 22 – Intensity of being engaged 23 – Extent of being involved in the process 24 – Intensity of persistence 25 – Intensity of showing positive affect Framing (play cues) 26 – Skill of being engaged 27 – Extent of giving cues 28 – Skill of giving cues 29 – Skill of responding to cues I-subtype HI-subtype C-subtype 3.58† )1.47 0.13 3.63† 3.88† )0.50 )0.17 )0.05 )0.20 0.16 0.46 4.00† )2.07† 0.90 )0.58 )2.19† )2.58† 0.27 1.24 1.25 0.28 )0.66 )0.42 )2.12† )2.25† 1.10 0.00 )2.07† )2.15† 0.60 )0.80 )0.99 0.19 0.73 0.07 )2.66† )1.06 )0.58 )0.43 )1.08 )3.59† )0.59 )4.10† )0.81 0.82 0.57 )1.07 )0.75 2.10† 0.08 3.00† 0.47 0.42 0.05 1.40 1.85 2.25† 0.59 2.10† 0.39 )0.57 )2.36† 0.30 0.63 )1.01 0.05 1.65 )0.41 0.57 0.69 0.92 1.52 0.22 )1.30 0.58 )0.29 )0.81 )0.61 3.61† 0.43 0.55 0.42 )2.03† 0.01 0.73 0.61 )2.25† *t-values reflect the direction and significance of the distance from the estimated parameter. †Values of significance (t-values > 1.96; t-values < )1.96). C-subtype, combined; HI-subtype, hyperactive-impulsive; I-subtype, inattentive. However, our results did not support Baeyens et al.’s (2006) findings that children with the I-subtype experience difficulty in ‘skill to transition ⁄ shift between activities (9)’ or with ‘persistence (24)’. That is, our findings suggest that although children with the I-subtype experienced difficulty with intense involvement, they persisted with activity that they did find to be motivating. Children with the HI- and C-subtypes struggled on several social items. This is in line with previous findings that children with the HI- and C-subtypes have a tendency to butt in and take things from others; are unable to wait their turn; are not considerate of others’ feelings (Diamond, 2005) and have a tendency to initiate play in destructive ways or fail to initiate play at all. Perhaps these characteristics collectively help explain why children with the HI- and C-subtypes are more likely than children with the I-subtype to be rejected by peers (Diamond). Children with the HI- and C-subtypes also found ‘playful mischief (17)’ and ‘clowning (19)’ to be relatively Journal compilation C C 2010 The Authors 2010 Australian Association of Occupational Therapists 143 ADHD SUBTYPES AND PLAY I-subtype 5 HI-subtype C-subtype Freedom from constraints of Reality Perception of control Motivation Framing Diagnosis: t-value relative-to-overall (+) 4 3 2 +1.96 1 0 –1 –1.96 –2 –3 –4 28. GiveCues_S 29. RespondCues_S 27. GiveCues_E 25. Affect_I 26. Engaged_S 24. Persist_I 23. Process_E 22. Engaged_I 21. Engaged_E 20. ClownJoke_S 19. ClownJoke_E 18. MischiefTease_S 17. MischiefTease_E 16. Unconventional_S 14. Pretend_S 15. Unconventional_E 13. Pretend_E 11. SocialPlay_I 12. SocialPlay_S 10. SocialPlay_E 8. Modifies_S 9. Transitions_S 6. InteractObject_I 7. InteractObject_S 4. Share_S 5. Support_S 3. Decide_E 1. Initiate_S 2. Negotiate_S –5 FIGURE 1: Bias interaction of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder subtypes and Test of Playfulness items. easier than predicted, whereas children with the I-subtype found them to be more difficult. These findings may reflect previous research, suggesting that children with the HI- and C-subtypes are more extroverted, less selfconscious and more animated than children with the I-subtype. In contrast, children with the I-subtype are known to be more introverted, self-conscious and passive (Barkley, 2003; Diamond, 2005; Gaub & Carlson, 1997); their more self-conscious play style was particularly evident in relatively lower scores on ‘clowning’ (19) and ‘mischief’ (22). Previously, we suggested that the constellation of low ToP scores of children with ADHD, compared with those of typically developing children, was indicative of difficulty with interpersonal empathy (Cordier et al., forthcoming). In coming to this conclusion, we employed a three-part definition of empathy described by Feshbach (1997): (i) ability to discriminate and identify the emotional state of another; (ii) capacity to take the perspective of another; and (iii) evocation of a shared affective response. We proposed that difficulties with empathy were reflected in low scores on several ToP skill items considered together: ‘supporting the play of others (5)’, social play (12)’, ‘responding to play cues (29)’ and sharing (4)’. However, the current findings suggest that reduced empathy may be more characteristic of children with the HI- and C-subtypes than those with the I-subtype. Lack of empathy combined with wilful non-compliance is characteristic of ODD and subsequent CD (American Psychiatric Association, 2000; Loeber, Burke, Lahey, Winters & Zera, 2000), two conditions that commonly cooccur, particularly in children with HI- and C-subtypes. Whereas mischief, by ToP definition, is not wilful noncompliance, several authors (Lahey & Loeber, 1994) have suggested that the behaviour of children with ADHD deteriorates across the lifespan. For some children, mischief and clowning may begin as a means of trying to engage other players. However, if unsuccessful (as unskilled mischief often is), it may turn into defiant behaviour (e.g. breaking important rules and committing aggressive acts). A possible link between mischief and oppositional behaviour of children with the HI- and C-subtypes is supported by concomitant high CPRS-R Oppositional Subscale scores and higher than expected ToP scores on extent of ‘mischief (17)’ and ‘clowning (19)’ (see Tables 2 and 3). Limitations It was not feasible to draw a random sample. Hence, the ability to generalise the results of this study to children with ADHD in other populations is somewhat limited. However, the strength of the results indicates the need for further research. Conclusions and implications for research and practice Our results reveal similarities in play patterns of children with HI- and C-subtypes and the possibility of a different hierarchy of ToP items for children with the I-subtype compared with those of children with the other two subtypes. Nonetheless, variability within the subgroups suggests that an individual child may be quite different from other children within the same subgroup. Therefore, the findings support the need to evaluate play for all children with ADHD and to target interventions to individual needs, particularly as play is the milieu within which children develop social skills and form peer relationships (Barkley, 2006). Further research is needed to replicate 2010 The Authors C 2010 Australian Association of Occupational Therapists Journal compilation C 144 R. CORDIER ET AL. the findings. Specifically, further research is needed to determine if children with the I-subtype respond differently from children with the other subtypes to play-based interventions. Although our findings cannot, and should not, replace assessment of play in an individual child, they do suggest that there are enough differences in the play patterns of children with the I-subtype compared with that of children with the HI- and C-subtypes to warrant consideration when planning intervention to improve play. For example, when therapists plan interventions for children with the I-subtype, it may be advantageous to include the usual playmate of the child with ADHD into the intervention. In fact, a usual playmate may help the child to counteract a typically passive style of interacting. Intervention might encourage the children to engage in playful mischief to increase the fun, capture the source of their motivation and promote engagement. Conversely, the following will more often need to be considered when planning interventions for children with the HI- and C-subtypes, helping a child: identify the emotional state of a playmate, take on a playmate’s perspective, share affective responses, understand the boundaries of playful mischief and clowning, initiate play activities appropriately and support the play of a playmate. Acknowledgements This study was completed by the first author as part of the requirements for the completion of a PhD under the supervision of the other authors. The authors wish to acknowledge the Australian Government for EIPRS and IPA scholarships, and express their gratitude to the families who participated in the research, and in particular to the staff from Whirinaki, Kari and Marinoto North Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services, New Zealand. References Alessandri, S. M. (1992). Attention, play, and socialbehavior in ADHD preschoolers. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 20 (3), 289–302. American Psychiatric Association. (2000). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (revised 4th ed.). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association. Baeyens, D., Roeyers, H. & Vande Walle, J. (2006). Subtypes of attention-deficit ⁄ hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): Distinct or related disorders across measurement levels? Child Psychiatry and Human Development, 36, 403–417. Barkley, R. A. (2003). Issues in the diagnosis of attentiondeficit ⁄ hyperactivity disorder in children. Brain and Development, 25, 77–83. Barkley, R. A. (2006). A theory of ADHD. In: R. A. Barkley (Ed.), Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: A handbook for diagnosis and treatment (3rd ed., pp. 297–336). New York: Guilford. Barnett, L. (1991). The playful child: Measurement of a disposition to play. Play and Culture, 4, 51–74. Bateson, G. (1971). The message, ‘‘this is play’’. In: R. E. Herron & B. Sutton-Smith (Eds.), Child’s play (pp. 261– 269). New York: Wiley & Sons. Bateson, G. (1972). Toward a theory of play and phantasy. In: G. Bateson (Ed.), Steps to an ecology of the mind (pp. 14–20). New York: Bantam. Bond, T. C. & Fox, C. M. (2007). Applying the Rasch model: Fundamental measurement in the human sciences (2nd ed.). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. Bundy, A. C. (2004). Test of Playfulness (ToP). Version 4.0. Sydney: University of Sydney. Bundy, A. C., Nelson, L., Metzger, M. & Bingaman, K. (2001). Validity and reliability of a Test of Playfulness. Occupational Therapy Journal of Research, 21 (4), 276–292. Carlson, C. L., Shin, M. & Booth, J. (1999). The case for DSM-IV subtypes in ADHD. Mental Retardation and Developmental Disabilities Research Reviews, 5, 199–206. Conners, C. K. (2004). ‘‘Validation of ADHD Rating Scales’’: Dr. Conners replies. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 43 (10), 1190–1191. Conners, C. K., Sitarenios, G., Parker, J. D. A. & Epstein, J. N. (1998). The revised Conners’ Parent Rating Scale (CPRS-R): Factor structure, reliability, and criterion validity. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 26 (4), 257–268. Cordier, R., Bundy, A., Hocking, C. & Einfeld, S. (forthcoming). Empathy in the play of children with ADHD. Occupational Therapy Journal of Research. Diamond, A. (2005). Attention-deficit disorder (attentiondeficit ⁄ hyperactivity disorder without hyperactivity): A neurobiologically and behaviorally distinct disorder from attention-deficit ⁄ hyperactivity disorder (with hyperactivity). Development and Psychopathology, 17, 807–825. Embretson, S. E. & Reise, S. P. (2000). Item response theory for psychologists. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. Feshbach, N. D. (1997). Empathy: The formative years – Implications for clinical practice. In: A. C. Bohart & L. S. Greenberg (Eds.), Empathy reconsidered: New directions in psychotherapy (pp. 33–59). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. Gaub, M. & Carlson, C. L. (1997). Behavioral characteristics of DSM-IV ADHD subtypes in a school-based population. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 25 (2), 103–111. Graetz, B. W., Sawyer, M. G., Hazell, P. L., Arney, F. & Baghurst, P. (2001). Validity of DSM-IV ADHD subtypes in a nationally representative sample of Australian children and adolescents. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 40 (12), 1410–1417. Hale, J. B., How, S. K., Dewitt, M. B. & Coury, D. L. (2001). Discriminant validity of the Conners’ Scales for ADHD subtypes. Current Psychology, 20 (3), 231–249. Lahey, B. B. & Loeber, R. (1994). Framework for a developmental model of oppositional defiant disorder and conduct disorder. In: D. K. Routh (Ed.), Disruptive behavior disorders in childhood (pp. 139–180). New York: Plenum Press. Leipold, E. E. & Bundy, A. C. (2000). Playfulness in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Occupational Therapy Journal of Research, 20 (1), 61–82. Journal compilation C C 2010 The Authors 2010 Australian Association of Occupational Therapists 145 ADHD SUBTYPES AND PLAY Linacre, J. M. (2007). Winsteps Rasch measurement: Computer software and manual (Version 3.62.0). Retrieved 13 June 2008, from http://www.winsteps.com Loeber, R., Burke, J. D., Lahey, B. B., Winters, A. & Zera, M. (2000). Oppositional defiant and conduct disorder: A review of the past 10 years, Part I. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 39 (12), 1468–1484. Melnick, S. & Hinshaw, S. (1996). What they want and what they get: The social goals of boys with ADHD and comparison boys. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 24 (2), 169–185. Milich, R., Balentein, A. C. & Lynham, D. R. (2001). ADHD combined type and ADHD predominantly inattentive type are distinct and unrelated disorders. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 8 (4), 463–488. Neumann, E. A. (1971). The elements of play. New York: MSS Information. Skard, G. & Bundy, A. C. (2008). Test of Playfulness. In: L. D. Parham & L. S. Fazio (Eds.), Play in occupational therapy for children (2nd ed., pp. 71–93). St Louis: Mosby. Wendt, A. & Surges-Tatum, D. (2005). Credentialing health care professionals. In: N. Bezruczko (ed.), Rasch measurement in health sciences: Measurement axioms (pp. 161–175). Maple Grove, MN: JAM. 2010 The Authors C 2010 Australian Association of Occupational Therapists Journal compilation C