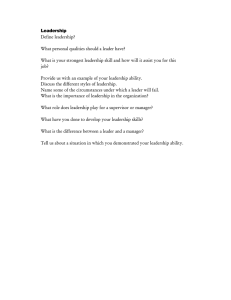

FUNCTIONAL LEADERSHIP

advertisement

FUNCTIONAL LEADERSHIP INTRODUCTION This Training Note is intended to provide information to students attending courses on the subject of "Functional Leadership" as relevant to the Rescue and Fire Fighting Services (RFFS) employed at airports. AIM To understand fully what is meant by the term "Functional Leadership". OBJECTIVES At the end of the instructional session dealing with this subject, after detailed study of this note and the associated notes covering this subject you will: • Understand both the qualities and situational approach to leadership • Understand that the functional approach to leadership is a better approach in respect to the needs of the Fire Service today. • Understand the leadership functions of the Fire Officer. • Understand the different leadership styles. • Understand the importance of effective delegation. CONTENTS The subject will be dealt with under the following headings: • • • • • • • • • Introduction to Leadership. The qualities approach. The situational approach. The functional approach. Functional Leadership. Leadership functions of the Fire Officer. Leadership style. Delegation. Summary. INTRODUCTION TO LEADERSHIP Leadership training at the International Fire Training Centre is based on the functional approach to leadership training. The Fire Service is one of the first non-military organizations to adopt the functional approach. Before considering the functional approach, two earlier approaches must be reviewed. QUALITIES APPROACH The oldest idea and perhaps the most common assumption about leadership is that the leaders are born with inherent qualities which qualify them to lead; e.g. courage, integrity, commonsense, humor. Great leaders have been analyzed to see what qualities they displayed and lists of desirable qualities drawn up on the basis of this analysis. Unfortunately the approach breaks down on a number of points. Researchers into this approach assembled all the known lists of leadership qualities made by various authorities. There were many lists but no two lists agreed. Another fault is that we can all recall some leaders who were very effective yet obviously lacked some of the widely accepted qualities. For example, did Hitler have integrity or a sense of humour; did Churchill have tact? Again, do we not all know people who have many of the qualities yet are quite incapable of leading? If these qualities are necessary, to what degree are they needed? How much courage? Do not all fire-fighters or members of the Armed Forces need courage? Another problem is training. Can courage or a sense of humour be developed, or does it mean that some people are leaders and some are not and that this state cannot be changed? Finally there is the danger that the qualities approach suggests that leadership is a matter of being rather than doing. Although the qualities approach does not give an adequate explanation of leadership, there is an element of truth in the approach. People with certain qualities have a good starting point for leadership providing they recognize their assets and make use of them and recognize their weaknesses and overcome them. SITUATIONAL APPROACH The reverse side of the coin is the situational approach to leadership. This suggests that the leader in any group will be the person who possesses the necessary skill or knowledge to deal with the situation or problem facing the group. For example, in a party shipwrecked on an island, the builder, the doctor or the sailor might assume leadership according to the task to be achieved. However, the theory has weaknesses; knowledge or skill alone is not enough. We all know experts who are incapable of leading anyone. Something more than technical skill is needed. In an organization such as the Fire Service it would be unacceptable to pass leadership from one expert to another like a rugby ball; this would soon lead to disorder. Moreover, groups are seldom faced with single problems; there are usually conflicts of priority. For example, on the island the group might want to build a boat, care for the sick and provide themselves with a shelter at the same time. Who would then be the leader - the sailor, the doctor or the builder? So, the situational approach does not give the complete answer to leadership; however, it contains its grain of truth. Just as the qualities approach suggests that the possession of some qualities helps towards leadership if they are recognized and used, so too according to the situational approach, the person who has the most appropriate skill and knowledge in relation to the situation is likely to be a better leader. FUNCTIONAL APPROACH A better approach to leadership and leadership training is made by analyzing the functions involved. It must be borne in mind that leadership can only be applied to groups who are confronted with the need to take action or make decisions. People who are assembled passively, to watch a film for example, are not subject to leadership. A great deal of research has been made into the psychology of small groups both in industry and in the Armed Forces. From this research it has been found that within a group there exist three areas of need: Task Needs Groups arise or are formed to undertake tasks which are too difficult, too complex or too impractical for one person to accomplish alone. For example, to win a soccer game, to fly a large aircraft, to get to the top of a mountain, to keep the Station or Brigade functioning efficiently. This is the area of task needs. Team Maintenance Needs To achieve its objective the group has to be held together as a cohesive team, to work together in harness. For example, eleven star soccer players do not necessarily make a winning team. If they act as prim a Donnas, eleven lesser players working as a well knit team might beat them soundly. This is the area of team maintenance needs. Individual Needs In any group each individual brings his/her personal needs. The physical needs of food, shelter, warmth, clothing, money Psychological needs; to be accepted in to the group, to be given status, to be allowed to use skills and to contribute to the group, to achieve ambitions. FUNCTIONAL LEADERSHIP The Leader's Functions:With the recognition of the three areas of need, it can be seen that the job of the leader is to: Be aware of the needs of the group Perform the functions Thought processes Communications and Actions To satisfy the needs of the group To be aware of the needs of the group and to perform leadership functions, the leader has to have skill and training. If the leader does something to strengthen the team, by training for example, it will be more likely to achieve its task and each individual will feel more confident. Priority of Task Needs Figure 1 also shows the areas equal in size. However, in any circumstances particular needs are likely to predominate. For example, task need must predominate sometimes, especially in the Armed Services or emergency organizations such as the Fire Service. In these circumstances the leader must give priority to task needs at the expense of other areas of need, see Figure 2. On the other hand, if an individual has a weakness or a problem which stops the team from operating effectively to the detriment of the task, then attention to the individual needs becomes a priority, (see.Figure-3.) Task Team Individual Figure -1 The skilled leader builds up team and individual needs in slack periods in preparation for high task priorities. Team and individual needs can be thought of as batteries to be charged up. The skilled leader recognizes that after long task priority periods he/she must seize opportunities to attend to team and individual needs to recharge batteries. LEADERSHIP FUNCTIONS OF THE FIRE OFFICER In a Fire Service environment it is considered that the following are the six key functions which a leader must perform to meet the needs of the group: Planning o o o o o o Sizing up the situation. Determining the extent of the task. Obtaining all available information. Deciding plan of action and priorities. Estimating assistance. As action progresses. Adjusting the plan (see Evaluating). Briefing o o o o Explaining the aims and plan Giving reasons why? Allocating tasks to crews/individuals Setting crew standards. Controlling Maintaining crew standards. Influencing tempo. Ensuring all actions contribute to the aim. Supporting Encouraging crews/individuals. Disciplining crews/individuals. Creating team spirit. Informing Informing crews/individuals of all matters affecting their activities. Reporting back information from crews to higher command. Evaluating Comparing achievement with plan (in order to modify plan and/or take remedial action as required). Checking performance against the plan, if necessary adjusting the plan (see Planning). Helping the crew to evaluate its performance. Debriefing after fires or tasks. Giving credit and encouragement for good work. Pointing out mistakes and weaknesses. Discussing whether methods could be improved. Note:- It should be clear that failure to perform any one of these functions will result in the partial or total failure of the group to achieve its aim. Leadership Qualities In a fire fighting or rescue environment It is considered that the following are the ten essential elements of leadership: • Communication Informing crews/individuals of all matters affecting their activities. Reporting back information from crews to higher command. • Command Being in charge of the situation or taking over from an original leader. • Control Maintaining crew standards. Influencing tempo ensuring all actions contribute to the Aim. • Directing Recording, monitoring and evaluating progress of incident. • Delegation Granting authority or the right to make decisions to another team member. • Decision Making Addressing the problem of how a task is to be done. • Knowledge of Risk By using pre-determined action plan for different areas of the aerodrome and different fire hazards and risks, the leader will have a better knowledge of the action to take for given scenarios. • Safety Requirements Ensuring that the fire crew carry out their task with the minimum of risk to themselves. • Fitness Knowing and identifying when a team are exhausted and also knowledge that the leader himself may have to work on longer than the fire team. • Foresight Having the ability to anticipate the possible escalation of an emergency situation and plan accordingly. LEADERSHIP STYLE Commanders will vary their style of leadership according to the situation. On the fire ground leadership will be authoritarian and urgent, whereas in the fire station it may be of a more Consultative or democratic nature. This range of styles is illustrated overleaf by considering that most frequently arising leadership function: decision-taking. OSHA The way we perceive “The way things are around here”…can exert a great influence on leadership styles. We can associate three fundamental leadership styles to the three management imperatives discussed above. Let’s take a look at this association. Tough-coercive leadership In this leader ship approach, managers are tough on safety to protect themselves: to avoid penalties. The manger’s approach controlling performance may primarily rely on the threat penalties. To objective is to achieve compliance to fulfill legal or fiscal imperatives. The culture is fear-driven. Management resort to an accountability system that emphasizes negative consequences. By what mangers do and say, they may communicate negative messages to employee that establish or reinforce negative relationship. Here are some examples of what a tough-coercive leader might say; Punishment- “Of I go down… I’m talking you all with me “ (I’ve heard this myself) Punishment- “If you violate this safety rule, you will be fired.” Punishment- “If you report hazards, you will be labeled a complainer.” Negative reinforcement – “If you work accident free, you won’t be fired.” As you might guess, fear-driven cultures, by definition cannot be effective in achieving world-class safety because employees work (and don’t work) to avoid a negative consequence. Employees and managers all work to avoid punishment. Consequently, feardriver safety culture will no work. It cannot b e effective e for employees and managers at any level of the organization. It may be successful in achieving compliance, but that’s it. Tough-controlling leadership Manages are tough on safety to control losses. Hey have high standards for behavior and performance, and they control all aspects of work to ensure compliance. This leadership model is most frequently exhibited in the “traditional” management model. As employers gain greater understanding, attitudes and strategies to fulfill their legal and fiscal imperatives improve. They become more effective in designing safety systems that successfully reduce injuries and illnesses, hereby cutting production costs. Tight control is necessary to achieve numerical goals. Communication is typically topdown and information is used to control. A safety “director” is usually appointed to act as a cop: responsible for controlling the safety function. Tough-controlling leaders move beyond the threat of punishment as the primary strategy to influence behavior. However, they will rely to a somewhat lesser extent on negative reinforcement and punishment to influence behavior. Positive reinforcement may also be used as a controlling strategy. Though-controlling leadership styles may or may not result in a fear based culture. Examples of what you might hear from a tough-controlling leader include: Negative reinforcement ‘“If you have can accident, you’ll be disciplined.” Negative reinforcement ‘“If you don’t have an accident, you won’t lose your bonus.” Positive reinforcement ‘“If you comply with safety rules, you will be recognized.” Tough-caring leadership model Managers are tough on safety because they have high expectations and they insist their followers behave, and they care about the success of their employees first. This is a selfless leadership approach. The tough caring leadership model represents a major shift in leadership and management thinking from the selfish tough controlling model. Managers understand that complying with the law, controlling losses, and improving production can best be assure d if employees are motivated, safe, and able. Management understands that they can best fulfill their commitment to external customers by fulfilling their obligations to internal customers: their employees. Communication is typically all way: information is used to share so that everyone succeeds. A quantum leap in effective safety (and all other functions) occurs when employers adopt a tough-caring approach to leadership. Rather than being the safety cop, the safety managers are responsible to ‘help” all line managers and supervisors “do” safety. Line managers must be the cops, not the safety department. This results in dramatic positive changes in corporate culture which is success-driven. Although positive reinforcement is the primary strategy used to influence behaviors, tough caring leaders are not reluctant in administering discipline when it’s justified because they understand it to be a matter of leadership. However, before they discipline, mangers will first evaluate the degree to which they, themselves, have fulfilled their obligations to heir employees. If they have failed in that effort, they will apologize and correct their own deficiency rather than discipline. What are you likely to hear from a tough-caring leaders? Positive reinforcement – “If you comply with safety rules, report injuries and hazards, I will personally recognize you.” Positive reinforcement ‘ “If you get involved in the safety committee, you will be more promotable.” Positive reinforcement – “If you suggest and help make improvements, I will personally recognize and reward you.” You can imagine that in a tough-caring safety culture, trust between management and labor is promoted through mutual respect, involvement and ownership in all aspects of workplace safety. Are you really committed? Show me the time and money. Top management may communicate their support for safety, but the real test for commitment is the degree to which management acts on their communication with serious investments in time and money. When management merely communicates their interest in safety, but does not follow through with action, they are expressing moral support, not commitment.