International Responsbility-Sharing for Refugees

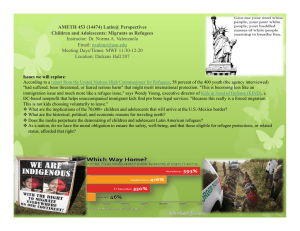

advertisement