APUSH Chapter 16 Brinkley

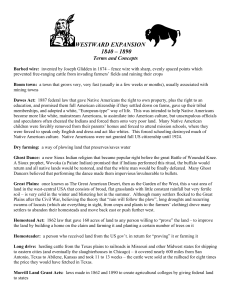

advertisement