Dr. David Cababaro Bueno- 21st Century Instructional Leadership Skills and School Culture

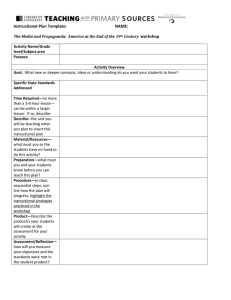

advertisement