Chlamydia Screening in New Zealand

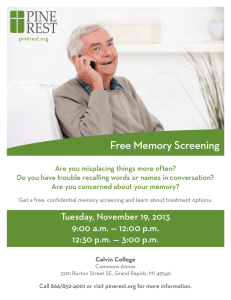

advertisement