Public Funding and Support of Assistive Technologies for

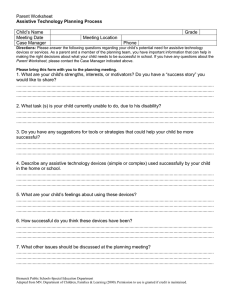

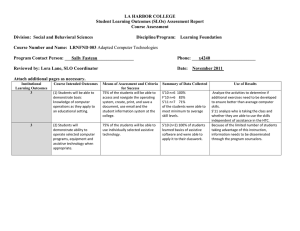

advertisement