Assessing the risk from environmental cadmium exposure

advertisement

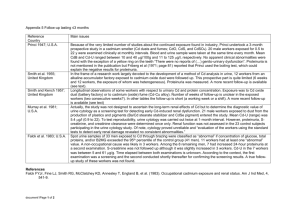

Journal of Public Health Medicine Vol. 18, No. 4, pp. 432-436 Printed in Great Britain Assessing the risk from environmental cadmium exposure Annette L. Wood Background Previous soil surveys by Environmental Health Officers had found high soil cadmium (Cd) concentrations in gardens next to a battery factory in Worcestershire. This study was set up to determine whether this had resulted in high Cd levels in the blood and urine of local residents. Methods A sample of residents (n = 39) living next to the factory were matched by age and sex to employees of North Worcestershire Health Authority. A questionnaire was used to determine potential Cd exposure. The levels of Cd in blood, urine and garden soil were measured. Results None of the members of the study group had a blood or urine Cd concentration above the levels estimated to cause harm. Only one member of the comparison group, but all members of the study group, had soil in their gardens with a Cd concentration above the recommended level. Adjusting for smoking status and other confounders by using logistic regressional analysis showed that being in the study group did not confer a greater risk of having an elevated blood or urine Cd concentration. The greatest influence on Cd concentrations was a current smoking habit. Conclusions No evidence was found to show that the high soil cadmium concentrations had adversely affected the health of local residents. Specific issues raised during the implementation of this study were the resource implications of assessing environmental exposure and the difficulties in recruiting the study group. Health Authorities and local government need to be fully aware of similar problems they might encounter before investigating a potential environmental health hazard. Keywords: cadmium; chronic environmental exposure; cross-sectional study with matching Introduction There are three main sources of exposure to cadmium (Cd): inhalation, either from ambient air or from the tobacco smoke of cigarettes,1 3 and also eating food grown in Cd-contaminated soil.4 Exposure to excessive levels of Cd can eventually lead to renal damage, the first sign of which is a tubular type of proteinuria.5 Once fully established, the renal dysfunction is irreversible, even if exposure subsequently ceases.6 Numerous epidemiological studies of workers have documented the spectrum of effects that Cd exposure can produce.6"10 Less information is available on chronic environmental exposure to doses of Cd smaller than those experienced in occupational settings. Even so, recommended levels for soil Cd concentrations" and daily Cd intake have been issued in the past.12 In 1980, the World Health Organization (WHO) recommended that the Cd concentration of urine should not exceed 10 /ig/g creatinine and that control measures be applied as soon as the individual Cd level in urine exceeded 5 jig/g creatinine.13 However, these values were based on occupational Cd exposure and the validity of their extrapolation to environmental exposure in the general population has been questioned.14^16 Battery production in Worcestershire In 1920, a factory producing Cd-containing batteries was first established in Redditch, Worcestershire. Soil sampling around the perimeter of the factory in the mid-1980s by Redditch Environmental Health Department had indicated higher than normal concentrations of Cd. When re-landscaping of the area was due in the late 1980s, a sampling exercise involving local gardens found that only four from 126 samples were under the recommended level for Cd in vegetable gardens of 3 mg/kg dry soil weight." Produce sampling also found high Cd levels in vegetables. The soil monitoring continued and the soil cadmium concentration remained high. Local residents were advised at this point not to eat vegetables grown in their gardens. However, it was not known how much of the cadmium had been ingested and absorbed, and the effect of the Cd on the health of the local population was not North Birmingham Health Authority, Birmingham Communicable Disease Unit, Bordesley House, 45 Bordesley Green East, Birmingham B9 5ST. ANNETTE L. WOOD, Senior Registrar in Public Health Medicine © Oxford University Press 1996 Downloaded from http://jpubhealth.oxfordjournals.org/ at Pennsylvania State University on March 3, 2014 Abstract 433 ENVIRONMENTAL CADMIUM EXPOSURE known. This cross-sectional study with matching was set up to compare the Cd concentrations in the blood and urine of residents living next to the battery factory, where the soil Cd concentration was highest, with those of a group of non-residents, matched for age and sex. The study was carried out between October 1993 and April 1994. Method data collected were analysed using EPI INFO 5.6 and SPSS18 software packages. Results The study group consisted of 16 women and 23 men. Their ages ranged from 19 to 64 years. Nine were aged under 30 years and four were aged over 59 years. The mean age was 40 years for the men and 39 years for the women. The length of residence ranged from less than one year to 62 years. Ten people had lived in the area for over ten years, six of whom were men. Fifteen male members and nine female members of the study group were current smokers. In the comparison group, five of the men and none of the women were current smokers. Ten matched pairs from the male groups and seven from the female groups had similar smoking habits. Fifteen people in the study group and ten in the comparison group ate vegetables grown in their own garden. No-one had a past medical history that would suggest a compromised renal system. The results of the sampling survey found that only one soil sample from the comparison group but all the samples from the study group were above the advised limit for Cd concentrations in vegetable gardens of 3 mg/kg dry soil weight (Table 1). None of the urine or blood Cd concentrations for members of both study and comparison groups were above the levels consid113 61925 ered hazardous to ' Analysis using logistic regression Logistic regression analysis was used to investigate the effect of confounders. All subjects with a urine Cd concentration of greater than 0-5 /xg/g creatinine and a blood Cd concentration of greater than 1 ng/\ were considered 'high'. Those with levels below this were considered 'low', thus creating a binary variable. Logistic regression models were then constructed TABLE 1 Summary of cadmium concentrations Women Blood (M9/0 Urine (w3/g creatinine) Soil (mg/kg dry soil) Men Blood (/ig/l) Urine (/ig/g creatinine) Soil (mg/kg dry soil) Range 1for groups Median for groups Mean for groups Study Comparison Study Comparison Study Comparison 0-3-0 0-1-25 76-78 7 0-1-0 0-0-5 0-5-2 0-8 0 26-3 0 0 0 0-98 032 356 02 005 0-59 0-3-1 0-0-88 7-6-78-7 0-5-1 0-1-8 0-1-7 1 0 31 1 0 0 089 0-21 37-5 0-69 0-14 0-38 Downloaded from http://jpubhealth.oxfordjournals.org/ at Pennsylvania State University on March 3, 2014 Introductory and reminder letters explaining the aim of the study were sent to those residents on the electoral register living nearest the factory who were aged between 18 and 65 years (n = 116). Residents who had worked in industries where they were likely to be exposed to cadmium were excluded. Thirty-nine eligible people (34 per cent) agreed to take part. A comparison group was obtained from the employees register of North Worcestershire Health Authority who were matched to the study group by age and sex and who did not live near the battery factory. Again, employees who had worked in industries where they were likely to be exposed to cadmium were excluded. Both groups were sent a letter giving more details of the study and a consent form. They were asked to complete a standard structured questionnaire to determine their medical, smoking and occupational histories and whether they ate vegetables grown in their gardens. Instructions on how to collect a soil sample from the garden were given. Arrangements were made to take a sample of venous blood, and at the same time an early morning midstream urine specimen and a soil sample were collected. All blood and urine samples were analysed at the West Midlands Regional Toxicology Laboratory. The limit of detection of Cd for both blood and urine assays was 0-5/xg/l. All soil samples were analysed at the County Scientific Laboratory. The limit of detection for the soil samples was 0-2 mg/kg dry soil weight. All 17 434 JOURNAL OF PUBLIC HEALTH MEDICINE TABLE 2 Logistic regression analysis Blood cadmium high Urine cadmium high Relative risk 95% Cl Relative risk • vegetables 226 6-46 1-70 1-12 0-46-11-14 0-86-48-53 0-26-11-16 1-04-1-21 062 19-76 1-40 106 0-15-2 62 3 77-103-68 0-30-656 1-00-1-13 vegetables 2-33 2-26 3-65 1-11 0-49-11 03 0-41-12-47 0-69-19-23 1-04-1-19 0-77 8-12 4-55 105 0-20-2-99 1 -82-36-20 1-25-16-60 1-00-1-11 vegetables 2-35 11-44 028 1-30 1-13 044-12 52 1-09-119-76 0-05-1-62 0-17-9-75 1-04-1-23 0-66 2647 0-47 117 106 0-15-6-51 4-27-163-97 0-11-1-97 0-24-5-81 1-00-1-13 vegetables 2-40 3-24 0-38 3-49 112 0-48-1200 0-46-22-57 0-07-1 -96 0-64-19-10 1 03-1 -20 0-79 8-65 0-74 4-42 105 0-20-3-10 1-86-40-23 0-22-2-54 1-21-16-14 1-00-1-11 vegetables invalid model 0-66 106 0-47 2528 118 107 0-15-2-87 0-08-13-50 0-11-1 98 1 -80-355-24 0-23-5-98 1-00-1-13 Cl, confidence interval. using the SPSS software package in which variables were entered in a stepwise fashion (Table 2). The conclusions from the analysis were that current smoking and age were of borderline significance in relation to having a urine Cd level of more than 0-5 jig/g creatinine. After adjusting for other factors, only current smoking remained a significant risk factor for having a blood Cd concentration of over 1 /xg/1. Discussion An essential element of any investigation of exposure to potential environmental health hazards will be the assessment of risk.26 This study was set up to determine the Cd concentrations in the population potentially most at risk because they lived in the area with high soil Cd levels. The sample size was large enough to determine statistically significant results but would have had a detrimental effect on the power of the study, which is dependent on both the sample size and the magnitude of the effect being measured. The proportion of residents who were willing to take part in this study was disappointingly low, despite the fact that the issue of cadmium concentrations in the soil was known to local residents, some of whom had demanded a response from the local council. There was no evidence found to show that the high soil cadmium concentrations had resulted in high blood and urine Cd concentrations in local residents. This was probably as a result of the short length of time some residents had lived in the area and also the small proportion who ate vegetables grown in their gardens. However, if the study results had revealed blood and urine Cd concentrations that potentially could induce ill health, any subsequent study would have needed to overcome the logistical problems of establishing a larger study group. Downloaded from http://jpubhealth.oxfordjournals.org/ at Pennsylvania State University on March 3, 2014 Model 1 Ate home-grown Current smoker Study group Age Model 2 Ate home-grown Ever smoked Study group Age Model 3 Ate home-grown Current smoker Male Study group Age Model 4 Ate home-grown Ever smoked Male Study group Age Model 5 Ate home-grown Ever smoked Male Current smoker Study group Age 95% Cl ENVIRONMENTAL CADMIUM EXPOSURE Acknowledgements I would like to thank Dr Robin Braithwaite at the West Midlands Regional Toxicology Laboratory, Mr Bev Dickens at the Environmental Health Department of Redditch Borough Council, Dr Sarah Walters at the University of Birmingham and Dr Alan Tweddell at North Worcestershire Health Authority for their help and advice during the development and implementation of this study. References 1 Friberg L, Kjellstrom T, Nordberg GF. Cadmium. In: Friberg L, Nordberg GF, Vouk V, eds. Handbook on the toxicology of metals, 2nd edn. Amsterdam: Elsevier, 1986. 2 Elinder CG, Kjellstrom T, Lind B, el al. Cadmium exposure from smoking cigarettes: variations with time and country where purchased. Environ Res 1983; 32: 220227. 3 Lewis GP, Jusko WJ, Coughlin LL, Hartz S. Contribution of cigarette smoking to cadmium accumulation in man. Lancet 1972; 1: 291-292. 4 Tjell Jch, Christensen TH, BroRamussen F. Cadmium in soil and terrestrial biota with emphasis on the Danish situation. Ecotoxicol Environ Safety 1983; 7: 122-140. 5 Elinder CG. Normal values for cadmium in human tissues, blood and urine in different countries. In: Friberg L, Elinder CG, Kjellstrom T, Nordberg GF, eds. Cadmium and health - a toxicologicaJ and epidemiological appraisal'. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press, 1985. 6 Roels H, Djubang J, Buchet JP, Bernard A, Lauwerys R. Evolution of cadmium induced renal dysfunction in workers removed from exposure. Scand J Work Environ Hlth 1982; 8: 191-200. 7 Friberg L. Health hazards in the manufacture of alkaline accumulators with special reference to chronic cadmium poisoning. Ada Med Scand 1950; 138(240): 1-124. 8 Katanzis G, Flynn FV, Spourage J, Trott DG. Renal tubular malfunction and pulmonary emphysema in cadmium pigment workers. Quart J Med 1963; 32: 165-192. 9 Adams RG, Harrison JF, Scott P. The development of cadmium-induced proteinuria, impaired renal function and osteomalacia in alkaline battery workers. Quart J Med 1969; 152: 425-443. 10 Lauwerys R, Roels H, Regniers M. Significance of cadmium concentrations in blood and urine in workers exposed to cadmium. Environ Res 1979; 20: 375-391. " Interdepartmental Committee on the redevelopment of contaminated land. Guidance on the assessment and redevelopment of contaminated land. ICRCL 59(83), 2nd edn. London: ICRCL, 1987. 12 Joint FAO-WHO Expert Committee on Food Additives 1972. Evaluation of certain food additives and the contaminants mercury, lead and cadmium. FAO Nutrition Meeting Report Series Number 51. WHO Technical Report Series Number 505. Geneva: WHO, 1972. 13 World Health Organization Study Group. Recommended health based limits in occupational exposure to heavy metals. Tech Rep Ser Wld Hlth Org 1980; 647: 21-35. 14 Mueller PW, Jay Smith S, Steinberg KK, Thun MJ. Chronic renal tubular effects in relation to urine cadmium levels. Nephron 1989; 52: 45-54. 13 Jung K, Pergande M, Graubaum HJ, et al. Urinary proteins Downloaded from http://jpubhealth.oxfordjournals.org/ at Pennsylvania State University on March 3, 2014 Before the investigation of a possible association between a source of chemical pollution or contamination and ill health in a population is initiated, both the human and financial resource implications need to be taken into account. Joint working between local government and District Health Authorities can lead to logistical problems when the boundaries of authority either overlap or never meet. In this study, the local authority had a small budget to monitor the soil cadmium concentrations, whereas the Heath Authority did not have a specific budget for the investigation of environmental health hazards. As the laboratory costs alone for this study were £30 per person, the financial consequences of having to carry out a number of similar studies can be overwhelming. The investigation of environmental health hazards potentially exposes a human and financial resource deficit in District Health Authorities, which are expected to ensure they have adequate arrangements to deal with the health aspects of chemical contamination of air, soil, water and food.27"29 Health Authorities are also expected to designate an appropriate individual to be responsible for ensuring there is access to the necessary advice and expertise on the public health hazards arising from such chemical contamination.29 At present, responsibility for this often falls to the Consultant in Communicable Disease Control.30'31 However, the legitimacy of this has been questioned, in part because there is no recognized training in environmental health for public health physicians and microbiologists. Access to, and the availability of, expert advice can also be problematic. Examining the literature to determine whether some sort of 'past precedent' exists can lead to difficulties. As an example, studies investigating the effect of environmental Cd exposure have conflicting conclusions, in part because of the variety of biological parameters used, differences in the information collected about the study and comparison groups, and sample sizes which have ranged from over 1500 to less than 50.32"39 Measures to control the release of Cd into the environment have also varied over time and place, resulting in difficulties in estimating environmental Cd exposure. There are many potential hazards in the environment that it might be beneficial to know more about.40 However, if after initial assessment, no substantial risk can be found, it has to be considered whether time and resources are better spent elsewhere. This was considered to be the outcome of this study. 435 436 16 17 18 19 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 and enzymes as indicators of renal dysfunction in of the NHS and the role of others. H S G (93) 56. L o n d o n : chronic exposure to cadmium. Clin Chem 1993; 39(5): NHSME, 1993. 29 757-763. N H S M a n a g e m e n t Executive. Arrangements to deal with Bernard A, Thielemans N, Roels H, Lauwerys R. Associahealth aspects of chemical contamination incidents. H S G tion between NAG-B and cadmium in urine with no (93) 38. L o n d o n : N H S M E , 1993. 30 evidence of a threshold. Occup Environ Med 1995; 52: Gunnel] DJ. T h e public health physician's role in chemical 177-180. incidents. J Publ Hlth Med 1993; 15(4): 3 5 2 - 3 5 7 . 31 Dean AD, Dean JA, Burton JH, Dicker DR. EPl INFO Ayres PJ. Major chemical incidents - a response, the role of Version 5: a word processing, database and statistics the C o n s u l t a n t in Communicable Disease C o n t r o l a n d program for epidemiology on microcomputers. Atlanta, the case of need for a national surveillance resource G A : C e n t e r for Disease C o n t r o l , 1990. centre. J Publ Hlth Med 1995; 17(2): 164-170. 32 N o r u s i s M J . SPSS for Windows advanced statistics release Staessen J, Y e o m a n W B , Fletcher A E , et al. Blood 6.0. C h i c a g o , IL: SPSS Inc., 1993. c a d m i u m in L o n d o n civil servants. Int J Epidemiol Buchet J P , L a u w e r y s R, Roels H , et al. Renal effects o f 1990; 19(2): 3 6 2 - 3 6 6 . 33 c a d m i u m b o d y b u r d e n of the general population. Lancet I n s k i p H , Beral V, M c D o w a l l M . M o r t a l i t y o f S h i p h a m 1990; 336: 6 9 9 - 7 0 2 . residents: 40 years follow-up. Lancet 1982; 1: 8 9 6 - 8 9 9 . 34 Roels H , B e r n a r d A , C a r d e n a s A , et al. M a r k e r s o f early L a u w e r y s R , B e r n a r d A , Buchet J P , et al. D o e s e n v i r o n m e n t a l e x p o s u r e t o c a d m i u m represent a health risk? renal changes induced b y industrial pollutants. I l l C o n c l u s i o n s from t h e C a d m i b e l s t u d y . Ada Clin Belg Application t o workers exposed t o c a d m i u m . Br J Ind 1991; 46(4): 2 1 9 - 2 2 5 . Med 1993; SO: 3 7 - 4 8 . 35 K a w a n d a T , T o h y a m a C, Suzuki S. Significance o f t h e K i d o T , N o g a w a K , O h m i c h i M , et al. Significance o f excretion o f u r i n a r y indicator proteins for a low level of urinary cadmium concentration in a Japanese population o c c u p a t i o n a l exposure t o c a d m i u m . Int Arch Occup environmentally exposed to cadmium. Arch Environ Hlth Environ Hlth 1990; 62: 9 5 - 1 0 0 . 1992; 47(3): 196-202. 36 Verschoor M , H e r b e r R, v a n H e m m e n J, W i b o w o A , I w a t a K , Saito H , M o r i y a m a M , N a k a n o A . Follow u p Zielhuis R. R e n a l function o f workers with low-level study of renal tubular dysfunction and mortality in c a d m i u m e x p o s u r e . ScandJ Work Environ Hlth 1987; 13: residents of an area polluted with cadmium. Br J Ind Med 232-238. 1992; 49: 736-737. 37 C h i a K S , O n g C N , O n g H Y , E n d o G . Renal t u b u l a r Nishijo M , N a k a g a w a H , M o r i k a m a Y , et al. M o r t a l i t y of function of w o r k e r s exposed to low levels of c a d m i u m . Br inhabitants in an area polluted by cadmium: 15 year J Ind Med 1989; 4 6 : 165-170. follow up. Occup Environ Med 1995; 52: 181-184. M Sangster B, de G r o o t G, Loeber JG, et al. Urinary excretion Mueller P W , Paschal D C , H a m m e l R R , et at. C h r o n i c renal of cadmium, protein, beta-2-microglobulin and glucose effects in three studies of m e n a n d w o m e n occupationally in individuals living in a cadmium-polluted area. Human exposed t o c a d m i u m . Arch Environ Contam Toxicol 1992; Toxicol 1984; 3: 7 - 2 1 . 23: 125-136. 39 K a w a n d a T , K o y a m a H, Suzuki S. C a d m i u m , N A G Vather M . Assessment of exposure to lead and cadmium activity, a n d /J-2-microglobulin in the urine of c a d m i u m through biological monitoring - results of a U N E P / pigment w o r k e r s . Br J Ind Med 1989; 46: 5 2 - 5 5 . W H O study. Environ Res 1983; 30: 9 5 - 1 2 8 . 40 C o g g o n D . Assessment o f exposure t o environmental Archibald C P , Kosatsky T . Public health response t o a n p o l l u t a n t s . Occup Environ Med 1995; 52: 5 6 2 - 5 6 4 . identified environmental toxin: m a n a g i n g risks t o t h e James Bay Cree related t o c a d m i u m in caribou a n d N H S M a n a g e m e n t Executive. Emergency planning in the m o o s e . Can J Publ Hlth 1991; 82: 2 2 - 2 6 . NHS: Health Service arrangements for dealing with major incidents. E L (91) 137. Heywood: N H S M E , 1991. N H S M a n a g e m e n t Executive. Public health: responsibilities Accepted on I May 1996 Downloaded from http://jpubhealth.oxfordjournals.org/ at Pennsylvania State University on March 3, 2014 20 JOURNAL OF PUBLIC HEALTH MEDICINE