PUTTING BUDDHIST UNDERSTANDING BACK INTO

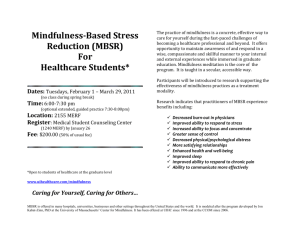

advertisement