Resonant mid-range WPT - CEI – Centro de Electrónica Industrial

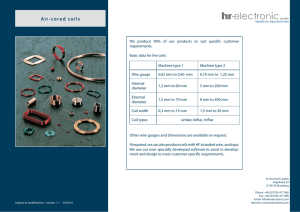

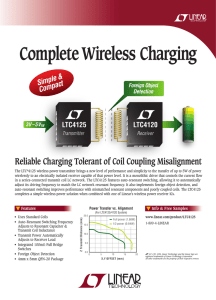

advertisement