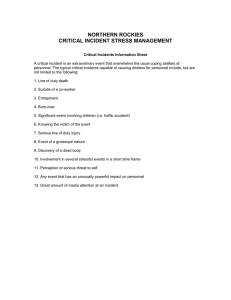

Standards for critical incident reporting in critical care

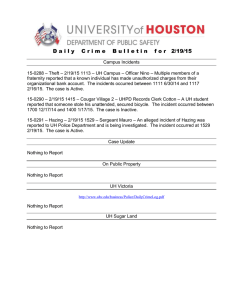

advertisement