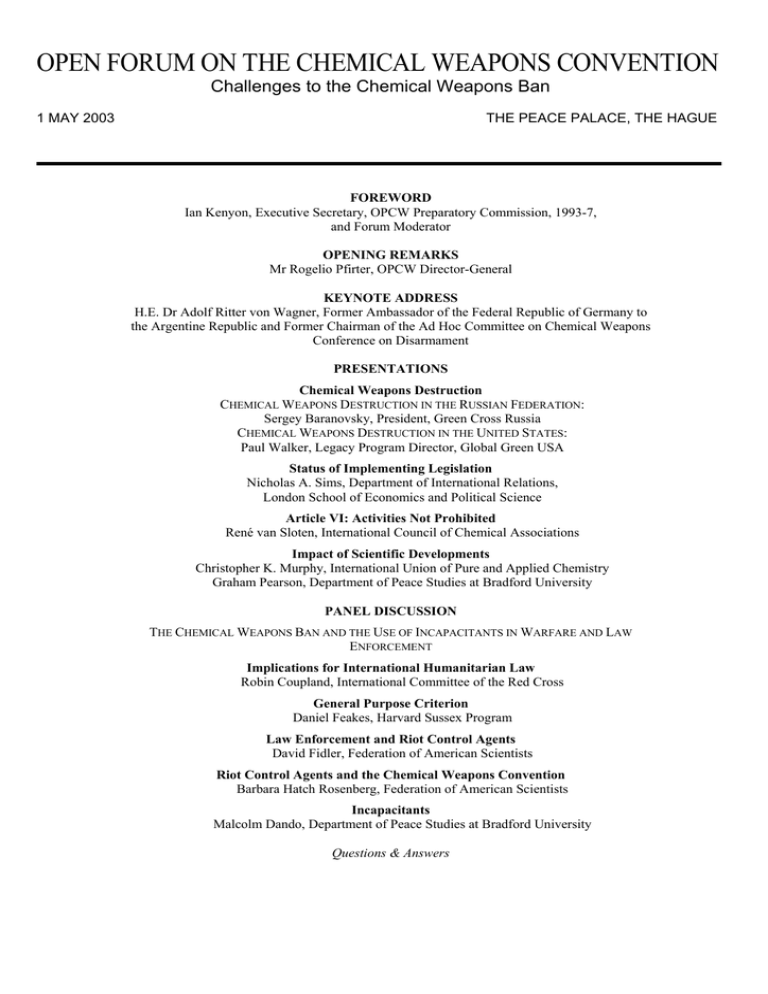

open forum on the chemical weapons convention

advertisement