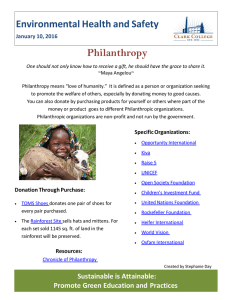

Inspiring local philanthropy

advertisement