Rigid Aluminum Conduct - The Aluminum Association

advertisement

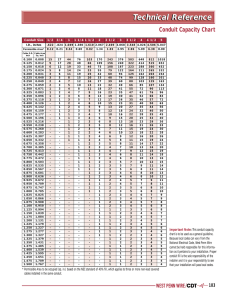

Section VI Related Structural Applications of Aluminum Chapter 17 Rigid Aluminum Conduct One of the earliest. and still most effective, methods of installing concealed electrical cable within the structure of a building, in the building foundations or the sub grade is the use of rigid conduit. The many advantages rigid conduit provides include, A very high order of mechanical and flame protection for the enclosed cables. A high order of safety to personnel who might otherwise accidentally come in contact with the ungrounded portion of the electrical system. An easy pulling, smooth, snag-free pathway for the cables through an otherwise intricate, many-turned run. Pull-boxes to enable straight pulls as required. An easy means for replacing conductors or pulling in additional ones. Permanent, built-in cable runways in cast concrete structures. Elements of Conduit Design Important elements in the design of electrical conduit He related to, Adequate strength in relation to size for self-support over reasonable lengths. Smooth, round, burr-free interior. Capability of being cut and threaded readily and bent smoothly (no flattening) with normal field methods and tools. Provision and maintenance of good electrical conduc­ tivity through the conduit proper and across all threaded joints. Development of a compatible line of accessories, such as elbows, couplings. unions, tees, pull and junction boxes. Freedom from destructive corrosion in the working environment. Provision for expansion fittings for long lengths oper­ ating under widely varying temperature conditions. installation and construction requirements for electrical conduit are set by the National Electrical Code (NEC). These include rigid aluminum, galvanized steel, IMC (intermediate metal conduit) and nonmetallic conduit, as well as conduit fittings, conduit bodies and boxes in aluminum, galvanized steel and PVC. Individual product lines must be manufactured to conform to the standards set forth by Underwriters Laboratories, in order to qualify for UL Labels. The factors involved in NEC rigid conduit specifications relate to installation and operating requirements. For example, the Code specifies maximum allowable fill areas for given conduit sizes. Table 17-1, abstracted from the 1987 NEC, shows the allowable fill area for each conduit trade size. * Table 17-3 gives cross-sectional areas for typical conductor sizes insulated with both thermosetting and thermoplastic materials. Table 17-4 converts these area limitations to the number of typical conductor sizes permitted in one conduit based on both thermosetting and thermoplastic insulations. Tables 17­ Sa and 17-5b give dimensions of rigid aluminum, galvan­ ized steel, andIMC. Table 17-6 gives comparative weights for the three types of metallic conduit. The NEC also recognizes the effect of the conduit or raceway on temperature rise of the encased conductor. In Chapter 9 of this book, Tables 9-3, 9-4, 9-5, 9-6 and 9-7 show characteristics of wires and feeders in magnetic and non-magnetic conduit or raceways. Metallic conduits can contribute a small amount of heating due to hysteresis (if the conduit is magnetic) and eddy current losses. Of greatest importance in its effect on ampacity, however, is the number of loaded conductors in a given conduit. The tables referenced above give ampacity data for the case of not more than three loaded conductors per conduit. When the number of conductors increases to from 4 to 6 the ampacity values are reduced to 80% of the tabulated value. If there are 7 to 24 conductors in the conduit, the allowable currents are to be reduced to 70% of the tabulated value. (The neutral conductors, since they only carry the unbalanced currents in normally balanced circuits, are not to be considered in determining '" Table 17~2 shows the maximum number of compact conductors allowable in conduit or tubing:. 17-1 related strudural applications of aluminum TABLE 17-1 Conduit-Allowable Fill Area Square Inches Conduit Trade Size Internal Total 1·Cond. 2-Cond. 3 or more Inches Area Sq. In. 53% 31% 40% 16 .28 .46 .80 1.08 1.78 2.54 3.91 5.25 6.74 10.60 15.31 09 .16 .27 .47 .63 1.04 1.46 2.29 3.07 3.94 6.20 8.96 % 1 1% 1% 2 2% 3 3% 4 5 6 I I I I i 30 .53 .86 1.50 2.04 3.36 4.79 7.38 9.90 12.72 20.00 28.89.. ---~~ .. i I i ! i , 12 .21 .34 .60 .82 1.34 1.92 2.95 3.96 5.09 8.00 11.56 i , I TABLE 17·2 Maximum Number of Compact Conductors in Trade Sizes of Conduit or Tubing l:.l Insulation Type ! .!TTX!TT Conductor H 'H H Size ~ AWGor W H H W H I k 'l N ...W N eml i 1 In. 6 4 2 1 110 210 3/0 I I 410 250 300 350 400 500 600 700 750 1000 17·2 5 4 3 7 11/4 4 6 4 3 3 9 7 5 3 3 XIT T HIH H W W' H H in~ 13 11 12 9 8 8 7 6 6 4 4 5 4 3 3 3 3 3 3 N 1112 In. X'T T X.T T X I I T T Hi H H H'H H H I H H H! W H H W H H , W H Wi N W N W N Conduit Trade Size 2 in. 2112 In. ! 15 15 11 11 15 18 18 8 8 11 13 13 6 8 10 10 11 14 14 6 5 5 7 8 8 9 12 12 7 8 10 10 4 4 5 7 5 6 6 7 8 8 3 3 7 6 7 3 3 4 5 5 3 4 4 4 5 5 3 3 3 3 4 4 3 3 3 3 4 3 3 ~I X,T T X 'T HIH H H H H H H W H H W N W ~IW N T i 3 in. 3112 in. 4 in. i . 12 15 15 10 13 13 9 10 10.12 14 14 7 8 B 9 11 11 6 7 7 8 9 10 10 12 12 5 6 6 7 8 8 9 11 11 5 5 6 6 7 8 8 9 10 4 4 5 5 6 6 7 8 8 4 4 5 5 5 6 7 3 4 4 6 6 6 3 3 3 4 4 3 3 3 4 4 4 5 5 5 3 3 3 4 4 4 rigid aluminum conduit TABLE 17-3 Conductor Cross-Sectional Areas (Based on Table 5, Chapter 9, 1987 NEC) film, and excellent ductility and machinability are basic factors in its present wide acceptance. The following material examines in some detail how these plus factors compare with steel. APPROXIMATE AREA. SQUARE INCHES INSULATED CONDUCTOR ' WIRE ~-----------------1 SIZE,I Types Type AWG.: kemil RHH & RHW' Type THW THHN THWN 12 10 8 6 4 3 2 1 ,038 ,046 ,085 .. 124 .161 .182 .207 .272 .311 .358 .415 ,484 .592 ,025 ,031 ,060 082 ,109 .126 .147 .203 ,237 .276 .329 .390 .488 ,012 ,018 ,037 052 .084 .099 ,684 .568 .762 .629 697 ,832 1.026 1.158 1,225 1.291 1.421 1.548 1.953 2.275 2.593 2.901 -=~~~--~~~~ , I/O 2/0 310 4/0 250 300 350 400 836 50O 600 700 750 900 900 1000 1250 1500 1750 2000 , ,983 1.194 1,336 1.408 1.478 1.617 1.753 2.206 2.548 2.890 3.208 ,118 .159 .189 .226 .271 .328 A03 ,467 .531 593 .716 ,879 1.001 1.062 1.123 1,245 1.362 Type XHHW' BARE ,017 ,005 ,022 ,008 ,046 ,017 062 027 ,042 .084 ,099 .053 .118 .067 .159 .087 ,109 .189 ,226 .137 .271 .173 ,219 .328 , ,403 .260 .467 .312 ,531 .364 593 ..416 _­ ,520 .716 .904 .626 1.030 .730 1,094 .782 1.150 , .833 1.267 .933 1,389 1.039 1,767 1.305 2.061 1.561 2.378 1.829 2.659 2.087 i Composition and Manufacture: Rigid aluminum con­ duit is usually extruded from the magnesium-silicide, 6063-Tl alloy, though other alloys can be used which meet UL requirements. Being an extrusion, aluminum conduit is completely moisture-and vapor-tight. Also, extruded pipe provides a smooth, uniform interior surface, Weight Comparison: Aluminum conduit with aluminum couplings weighs approximately one-third of its galvanized steel counterpart, and one-half that of steellMC, This dif­ ference in weight is reflected in substantially greater ease and cost savings in installation. For example, a IO-foot standard length of 4-inch steel conduit weighs over 98 pounds and requires two men or a hoist to place it. The same size aluminum conduit weighs only 34 pounds and is handled easily by one man. The larger the conduit size, the greater the savings in labor. , "'RHH and RHW without outer covering are the same as THW, the der'dting amounts given above, Note 10 to NEC Tables 310-16 to 310-31 specifies when the neutral must be counted as a current-carrying conductor), Rigid Aluminum Conduit Aluminum rigid conduit has been widely used during the past five decades due to recognition that lightweight aluminum conduit offers several advantages over steel" including reduced costs of installation, increased cor­ rosion resistance and improved ground path. Advantages of Aluminum Conduit Aluminum's combination of light weight, relatively high electrical and thermal conductivity, protective oxide Electrical Characteristics Aluminum conduit alloy 6063 has about 1I4 the elec­ trical resistance of the usual galvanized mild steel conduit. In the installed condition, with couplings, elbows and boxes, a run of aluminum conduit will show about 4-112 times greater electrical conductivity, and if the installation is properly made will maintain its high value. Protective Capability: In a conduit/cable system when a phase-to-ground fault occurs, the conduit will normally carry most of the fault current-which can be quite high in value, Usually. the wiring system neutral is grounded at one point. The conduit may be grounded at many points. In any event, the fault current flowing in the conduit raises its potential above ground by an amount equal to the impedance drop to ground. The lower the installed conduit impedance to ground the less danger there is from fault! ground shocks, and in this respect the advantage of aluminum conduit is obvious. The lower resistance of aluminum conduit also means that ground current fault relaying is more reliable. It must be understood that rigid electrical conduit as installed per NEC requirements is normally not supposed to carry any ground currents; it is to act as a mechanical protection and carry current only in the case of a fault. The Code specifically· indicates that any neutral wires shall not be instailed in electrical continuity wi th the conduit and, if accidental continuities are found to exist between the neutral and the conduit, such neutral faults shall be cleared. This separation of neutral ground current *1987 National Electrical Code, Section 250-21 17·3 related structural applications of aluminum TABLE 17-4 Typical Number of Conductors Allowable in Trade Sizes of Conduit or Tubing ----------~---- Maximum Number of Conductors in Conduit" Wire Size AWG or kernil 14 12 10 8 6 4 3 2 1 1/0 2/0 3/0 ! I '!f.r A B 1250 1500 1750 2000 B A 1" A B 10: 24 16 39 8' 18' 13 29 4 6 6: 11 11 18 , 5 5 1 9 3: 3 4, 2 1 4i 6' 1 ! 1 1 2! 3, 4 1 1, 2 1 , 1 1 3 3 1 , 1 1 1' 2 6: 13 ! 4: 10 I i ! 4/0 250 300 350 400 500 600 700 750 800 900 1000 ,,"" I , ~I 1 1 1• 1 1' 1 ! 1: I 1 1 1' 1i 1 1 1 , 1%10 A B 69 40: 51 : 32 32 26 16 13 11 10 7 7 6 6 5 5 29 24 19 10 7 5 4 4 1! 3 1 2 1: 1 1 1 3 3 2 1 4 3 3 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 2 1 1 1 1 1 1 ! I i .... ~. I A B 3%:11 BA : 4" B: A B A 5" B 6" B A I 1 6' 5i 1 1 A : I 2 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 3" 2%/' 65 154 9~ 192 143 ! 157 53 114 76,164117 : 43 73 61 104: 95 160127 1631 i 22 36 32 51! 49 79,66 106 85' 136:133 16 26 23 37 36 5~148 76 62 98 97 154 141 12 16 17 22 27! 35 36 47 47 60 73 94 106 137 10 13 15 19 23 29 31 39 40 51 63 80 91 116 9 11 13 16 20 25' 27 33 34 43 54 67 78: 97 94 70 44 22 15 9 8 7 5 4 3 3 1! ! 2" A B l"ht A B I i 5 4 3 2 2 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 4 3 3 2! 1! 1' ! I I 8, 7, 6 5' 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 9 12' 14 18 19! 25, 25, 8 10 12 15 16, 21 21 7 8 10 13 14:I 17 18: 6 9 11 l2! 14 15 5 7 9, 10 12 13 7 8 10 10 6 4' 3 4' 5 61 7 8 9, 3! 4 3 7 8: 5 6 2 4 3 5 5'I 6 7: 4 41 5 6 1 2i 3 1 1 3 4 5 3 4 1 1 2 4 4 3 3 1 1 2, 2 3 3 4 1 1 1: 2 3 3 4 1 1 3 1 1 3 3 1 1 2 1 1 2 3 1: 1 1 2 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 , 1 1 1 1 1 7i ~I 32 27: 22 16 15 12 11 9 8 7 5 5 4 4 39 33 29 24 4! 5 3, 5 20 16 14 12 11 9 7 7 6 6 50' 42 35 29 24 20' 17 15 13 11 9 8 7 57 49 41 35 29 23 20' lSi 16 14 11 7i 10 9 9 6 7 6! 8 3, 6 5 I ;1 4 4 4 72 61 51 42 35 28 24 21 19 16 13 11 11 10 9 8 A - THW. RHH, RHW (Without outer covering). B - THWN and THHN. (XHHW in sizes #4 AWG through 500 kemil) see NEC, Chapter 9. Table 3 lor other sizes and types, flow from the conduit is very helpful in minimizing ac electrolytic corro:;;;)Tl~ and interference with communi­ cation circuits. Short Circuit Capability: Comparative short circuit tests' on aluminum and galvanized steel conduits have been made to determine their relative behavior under heavy fault conditions. Fig, 17-1 shows the temperature rise vs. time of 2-inch aluminum and steel conduits joined in series and subjected to a short circuit current flow of 22,200 amperes RMS, The steel conduit at the end of 10 seconds was buckling and dully glowing and its temperature rise was about 4-112 times as great as that of the aluminum -AlEE Paper DP 60-652, L. F. Roehman, 1960. 17-4 conduit. The steel couplings all smoked profusely and showed thread damage. In contrast. the aluminum con­ duits still retained their gummed labels and showed no signs of the heavy current passage after the test. Thus, despite the considerably lower melt-point of aluminum conduit. its ability to carry short circuit currents is greatly superior to galvanized steeL Circuit Voltage Drop: Aluminum conduit, being non­ magnetic, exhibits no hysteresis losses from alternating current fields, The net effect is that voltage drop in a typical three-phase feeder or branch circuit in aluminum conduit may be from 10 percent to as much as 20 percent lower than with a corresponding steel conduit. For con­ ductor sizes 250 kcmil and higher, this overall reduced voltage drop may permit the use of conductors one size rigid olum;num conduit TABLE 17-5a Dimensions-ll.igid Aluminum and Galvanized Steel Conduit Trade S;ze , 0.0. Inches .840 'h -Y.. 1.050 1.315 1.660 1.900 2.375 2.875 3.500 I Wan 1.0. Inches Thickness .622 .824 1.049 1.380 1.610 2.067 2.469 3.068 3.548 4.026 5.047 .109 .113 .133 .140 .145 .154 .203 .216 .226 .237 .258 : Length WID Coupling 9'_11%" 9'-11%." 9'-11" 9'-11" Threads Per Inch . 14 14 11 'h 11% 11'V2 1% 9'_11># 1'12 9'-11" 111.6 2 9'-10'hu 2'12 8 ! 9'-10%" 8 3 , '" 31.6 4.000~' 9 -IOV. 8 4.500 9'-10%" 8 4 5 5.563 ~10" 8 6 _ _-'--_-'6~.6~2.5 .~6.06'::5~.....L_-..:!.2:.::8~0_ _, 9'-1()':_.....L_--'S"--_ _ TABLE 17-5b Dimensions-!MC Conduit Types I & II Trade Size y, % 1 1% 1% 2 2% 3 3% 4 0.0. I Inches II 1.0. inches II Wall Thickn... I I II .815 1.029 1.290 1.638 1.883 2.360 2.S57 3.476 3.971 4.466 .833 1.043 1.308 1.653 1.893 2.368 2.S63 3.468 3.988 4.4S8 .675 .879 1.120 1.468 1.703 2.170 2.597 3.216 3.711 4.206 .673 .873 1098 1.437 1.677 2.152 2.553 3.178 3.668 4.168 .070 .075 .085 .085 .090 .095 .130 .130 .130 .130 .080 .085 .105 .108 .10S .108 .155 .155 .160 .160 or in some cases two sizes smaller is the governing concern. where voltage drop Corrosion Charaderislits 01 Rigid Aluminum Conduil Alloy 6063, which is commonly used for rigid aluminum conduit, has an industry maximum limit of 0.1 percent copper coment and 0.35 percent for iron (Table 17-7). Aluminum conduit has been used successfully for more than 50 years in many marine and corrosive industrial installations under conditions where galvanized steel coo­ duit should not be used. The galvanizing on a steel conduit acts as an anodic sacrificial metal coating and is continuously uwearing out." On the other hand, aluminum quickly builds up its refractory oxide layer which is relatively inert to most chemicals except strong alkalies and acids. This tough, protective skin automatically renews itself whenever the bare metal becomes exposed. Aluminum's resistance to atmospheric corrosion has ! Length WID Coupling 9'-11%." I 9#-11 %" 9'-11" 9'-11" 9'-11" Threads Per Inch 14 14 11% 11 YzI 11% 9'-11%" 11 Y, 8 8 8 9'-11%" 8 9'-11'~ 9'-10Y2" 9'-1OY," been demonstrated repeatedly by tests and research stud­ ies. Some of the results: No signs of corrosion were evident on rigid aluminum conduit when inspected 5 years after it was installed on cooling towers. Severe combinations of moisture and chemical-laden atmospheres at the installation had reo quired frequent replacement of rigid galvanized conduit, according to Paper CP 58-1072 of the American Institute of Electrical Engineers. Aluminum alloy 6063 was exposed to marine, industrial and rural atmospheres. After exposures of I, 2, 3,4 and 5 years, there appeared no significant effects on yield and tensile strengths. Atmospheric corrosion rates of four solid metals, as deter­ mined by a IO-year study project of an ASTM committee. are shown in Table 17-8. Broad Industrial Application: Installations of rigid alu­ minum conduit usually require no maintenance painting 17-5 related structural applications of aluminum TABLE 17·1 TABLE 17-6 Composition of Aluminum Conduit Alloy (6063) Weight Comparison per Hundred Feet* Trade Size I Rigid Aluminum Y, 28.1 % 37.4 54.5 71.6 88.7 118.5 187.5 246.3 295.6 305.2 478.9 630.4 1 1% 11;2 2 2,. 3 , 3;1 4 5 6 ! I Galvanized Steel 80.3 106.4 154.5 203.7 251.0 338.0 541.0 697.0 837.0 1003.0 1343.0 1823.0 IMe Type I Percentage Limits per Industry 57.0 Standards 78.0 112.0 144.0 176.0 235.0 393.0 483.0 561.0 625.0 i I Copper Silicon Iron Magnesium Manganese Chromium Titanium Zinc Others Aluminum *Nominal 0.10 0.20 0.35 0.45 0.10 0.10 0.10 0.10 0.15 max. to 0.6 max. to 0.9 max. max. max. max. max, Remainder • Alloys with up to 0.40% copper are ac· ceptab!e to Underwriters' laboratories, Inc.. for use in rigid aluminum conduit and fittings. or protective treatment, as may be required on steel cOn­ duit. Because its resistance to corrosion is greater than steel's, it is the choice for many severely corrosive in­ dustrial environments such as: sewerage plants, water treatment stations, filtration plants and chemical plants. Exposure to Galvanic or Electrolytic A ttack: Aluminum conduit should not be direct-buried in earth due to un­ predictable soil conditions of moisture, possible presence of strong electrolytes and stray electrical currents. If it is necessary to bury aluminum conduit, in accordance with the NEC, it should be thoroughly coated with coal-tar epoxy Or given a layer of half-tapped approved tape. Also, factory-applied PVC coatings are commercially available. Galvanic attack can occur when the aluminum forms the anode of a battery created by twO dissimilar metals in contact with an electrolytic medium. Stray alternating or direct currents can aggravate the galvanic action, eventually destroying the buried or embedded conduit. tives (to speed setting time), use of sea or brackish water. use of unwashed beach sand or other saline aggregate and similar materials. 2. A tow resistance conduit run should be maintained. 3. The circuit neutral should be grounded at one point and be insulated from and have no electrical contact with the conduit. The conduit should not carry any of the ground currents associated with normal operation. Hazardous Locations: Requirements of Article 500 of the NEC covering conduit installations in hazardous locations can be easily met with properly installed rigid aluminum conduit. The characteristics of aluminum conduit facilitate the installation of a tight explosion-proof system. Installation 01 Aluminum Conduit" Easier, safer workability adds to the many advantages of rigid aluminum conduit at every step of installation. Conduit Embedded in Concrete: In accordance with the NEe, aluminum conduit should not be embedded in con­ crete without approved protection because of the possibil­ ity of galvanic or electrolytic corrosion. Stray currents can aggravate the corrosion, severely damaging the con­ duit. If it is necessary to embed aluminum conduit in concrete, it should be given the same protection recom­ mended for direct·earth burial. Additionally, to mitigate the corrosion of all metallic conduit embedded in concrete: Cutting: Fast, easy cuts are handled well by standard cutting tools, which are generally used. Power saws and cutting wheels work fast and neatly on I-II2-inch and larger conduit; for smaller sizes (as for smaller steel con­ duit), an IS-tooth hacksaw is recommended for easy, neat cuts. Reaming, as required by the NEC, can be easily accomplished by conventional means. I. The concrete should contain no extraneously added chloride. Such chlorides can originate from concrete addi­ See also ChapleT 11 sections describing methods of installing cable in conduit and calculations of pulling tension. 17·6 Threading: Standard dies, used according to accepted good practices, thread aluminum rigid conduit faster than (j rigid aluminum conduit C F Steel 1600 BOO 1400 100 1100 600 '" 1000 .!!1 tr '" ;; " 500 ~ ~ '" n E ~ 800 400 600 300 100 400 Aluminum 100 200 0 0 I ! I ( 2- 4 ! I 5 6 ! 10 Seconds inch conduit ,22,200 amperes) Fig. 17-1. Measured temperature rise vs time for aluminum and steel conduit under shari circuit conditions. steel and with less effort. Hand threaders produce good threading on smaller sizes. Power threaders, however. can be used on all sizes and operated at maximum drive speeds. When using top drive speeds. and for longer !oollife. dies with 300 to 350 rake angles should be used. Standard cutting oils of known good quality are recommended for uniform threads. Bending: Sweeps, elbows, cross-overs. offsets-every type of bend is easily made in rigid aluminum conduit. Stan· dard hand and power benders produce smooth and exact bends in all conduit sizes. Standard EMT benders can be used on I-inch or smaller aluminum conduit for one-shot bends. Use an EMT bender one size larger than the conduit. Mechanical or power benders can be used on all sizes, provided they have shoes and action similar to those of an EMT bender. Joining: Adequate electrical conductance in a conduit sys­ tern requires tight joints. To simplify field joining. both threads of every length of rigid aluminum conduit should be lubricated in the field if not lubricated at the factory. (On field-cut threads. of course, a reliable quality lubricant containing zinc or graphite should be used). Proper lubri­ cation aids in assuming tight joints. a system that can be easily dismantled. and a permanent, low-resistant electrical ground path. Pulling: Modern equipment and faster, safer techniques that work well with aluminum conduit have been intro­ duced for fishing and pulling through all types of wire­ ways. Propelled Lines: C02 or air propelled lines of nylon or other plastic shoot through all sizes or rigid aluminum conduit. Small Conduit: In sizes up to i-il2-inch and on shorter runs - up to 100 feet - polyethylene fish tapes can be used effectively. Also recommended are round. flexible. speedometer-type steel cables. Use of flat steel tapes should be avoided' since they tend to jam in the bends or, if not used carefully, scrape and cut conduit walls. 17.7 related structural applications of aluminum TABLE 17-8 Atmospheric Corrosion of Solid Metals over a 10 Year Period Atmosphere ~ Desert Rural Coastal Location Aluminum* ___._ j.________ 1 Zinc .... Lead 0.000 0.001 0.004 0.028 0.031 0.025 0.005 0.023 0.020 0.052 0.047 0.046 0.010 0.042 0.021 0.068 0.190 0.190 0.009 0.019 0.022 0.016 0.017 0.027 Phoenix, Arizona Industrial State College, Pa. Key West, Fla. La Jolla, Cal if. New York, N.Y. Industrial Altoona, Pa. Coastal ____L_ Copper I Corrosion rate shown in average mils per year. Table based on ASTM data (Committee report). * Aluminum 1100. Aluminum conduit is usually made from aluminum alloy 6063, generally considered to be equivalent in corrosion resistance to aluminum 1100. **Prime western zinc. Larger Conduit: For pulling large conductors through larger conduit or longer runs, polypropylene rope is recommended. Steel pulling cables, especially when old or frayed, can damage steel or aluminum conduit. Fittings for Rigid Aluminum Conduit: Although galvan­ ized or plated steel fittings are permitted by the 1987 NEC and can be safely used with rigid aluminum conduit, good aluminum fittings result in a superior installation. An all-aluminum conduit run has better conductivity and provides safer ground protection. And aluminum's 17-8 non-magnetic property, in fittings as well as conduit, reduces ground current losses and voltage drops. Expansion loints: Linear expansion of rigid aluminum conduit is not a factor in most installations. If a straight run is unusually long or subjected to extremes of tempera­ ture, expansion fittings might be needed. A good general rule: use an expansion joint if the degree-feet of a run may exceed 10,000. (Degree-feet is the length of the run in feet mUltiplied by the temperture rise, OF.)