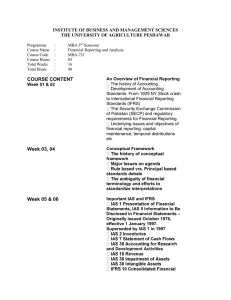

Analysts` Earnings Adjustments and Changes in Accounting

advertisement