THE “OWN NAME” DEFENCE TO TRADE MARK

advertisement

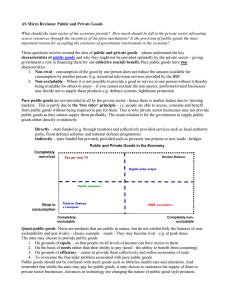

THE “OWN NAME” DEFENCE TO TRADE MARK INFRINGEMENT IN NEW ZEALAND* Kevin Glover Introduction There are very few provisions in New Zealand’s intellectual property statutes that have not been borrowed or adapted from other jurisdictions. One apparently unassuming exception to this general principle is section 13 of the Trade Marks Act 1953, which relates to the own name defence to trade mark infringement and its application in relation to companies. This section is an entirely indigenous creation, inserted in response to the 1950 Commission to Inquire into and Report upon the Law of Patents, Designs and Trade Marks (“Evans Commission”). It has never been adopted in any other jurisdiction. For nearly five decades the meaning of this provision was unclear. Curiously, in 2002 the provision was considered in two separate Court of Appeal cases following this half century of neglect. In Anheuser Busch Inc v Budweiser Budvar National Corporation,1 the majority of the Court held that the own name defence is available to companies under the Trade Marks Act 1953.2 In broad terms, this article analyses the Court of Appeal’s interpretation of section 13 of the Trade Marks Act 1953 in Anheuser Busch, and examines the application of the own name defence to companies in relation to trade mark infringement in New Zealand. The article begins by examining the own name defence as it applies in passing off and under the Fair Trading Act to examine the rationale behind the development of own name defences generally. The article then analyses section 13 and its effect on section 12(a) of the Trade Marks Act 1953 in light of the historical background to the enactment of those sections. Finally, the article considers the Court of Appeal’s decision on section 13 in Anheuser Busch, comments on the equivalent sections in the Trade Marks Act 2002 and a discusses the likely practical effects of the Court of Appeal’s interpretation of section 13. The own name defence to passing off The idea of an own name defence arose in relation to passing off before being introduced into trade mark law. Over time the existence of the own name defence to passing off has been hotly debated, but the balance of the authority tends to support the view that the defence is no longer available (if it ever was a defence in the first place). Initially no own name defence was recognised at law. In Reddaway v Banham,3 Lord Halsbury referred to it being a general principle of law that “nobody has any right to represent his goods as the goods of somebody else”, without qualifying that general statement of the law in relation to a defendant who uses his or her own name.4 The issue in Reddaway v Banham was * © Kevin Glover. Published in the New Zealand Intellectual Property Journal, May 2003: (2003) 3 NZIPJ 169. 1 [2003] 1 NZLR 472. 2 The other Court of Appeal case to consider section 13 was Advantage Group Limited & Ors v Advantage Computers Limited [2002] 3 NZLR 741. However, the Court decided the Advantage case upon grounds which made section 13 strictly irrelevant: para 38. 3 [1896] AC 199 (HL). 4 [1896] AC 199, 204. See also Ewing v Buttercup Margarine Co Limited [1917] 2 Ch 1. The fact that the defendant company had used its own name was in that case irrelevant to the question of liability for passing off in that case. Counsel for both parties focused on whether the public would be misled if the defendant were to trade under its name. The defendant’s barrister did not argue that an own name defence was available to save his client. Ultimately the fact that the defendant sought to trade under its whether the Court should issue an injunction to restrain the defendant from adopting a factually accurate trade name for products, the name having been chosen deliberately to appropriate the goodwill of the plaintiff. Lord Herschell discussed the importance of “secondary significations” associated with brand names, and referred to the case of Massam v Thorley’s Cattle Food Co.5 Lord Herschell surmised that: [T]he fallacy lies in overlooking the fact that a word may acquire in a trade a secondary signification differing from its primary one, and that if it is used to persons in the trade who will understand it, and be known and intended to understand it in its secondary sense, it will none the less be a falsehood that in its primary sense it may be true.6 That reasoning would seemingly exclude the own name defence from passing off altogether, since in the passing off context it is the impact of a representation on members of the public that is crucial, rather than the intention of the defendant in making the representation. The defendant’s conduct in making the representation is strictly irrelevant to whether or not the representation amounts to passing off. A claim that a defendant has simply used its own name is irrelevant to the question of liability, as is the defendant’s intention in choosing its name; the focus in passing off cases is the impact of the conduct upon members of the public. Despite this apparent conceptual impediment, judges in a number of cases still sought to create an exception to passing off for traders who used their own names. The New Zealand Supreme Court considered the own name defence to passing off in JJ Craig Limited v A E Craig and H R Craig in 1922.7 The plaintiff operated a transportation business which was well-known in Auckland. The defendants had previously worked for the plaintiff, but had decided to form their own business. The plaintiff sought to restrain the defendants from registering “The Craig Transport Company Limited” as a company name, or trading as a partnership under the name “The Craig Transport Company”. Salmond J noted at the outset of his consideration of the own name defence that the case law was complex and at times contradictory: The application of the rule as to passing-off to cases in which the instrument of deception is the use by the defendant of his own personal name is obscure and to some extent unsettled, and it is not easy to reconcile the decisions or dicta on this matter or to extract a definite principle from them.8 Salmond J distinguished between an individual’s use of his or her own name and a company’s use of its own name. The Court had some sympathy for the use of an own name by an individual. The Court observed: [A]n individual is entitled to trade under his own personal name regardless of the fact that his business may be thereby confused with the business of some other person bearing the same or a similar name. He is not even bound to take any special precautions to avoid or minimize such confusion. If there are two grocers named John Brown, each of them is equally entitled to trade under that name, and there is no priority of right in him who first establishes his business. … No man can by prior use acquire a monopoly in his own name.9 company name as registered was held to be irrelevant insofar as assessing liability for passing off was concerned. 5 (1880) 14 Ch D 748. 6 [1896] AC 199, 213. 7 [1922] NZLR 199. 8 At 206. 9 At 206-7. 2 The Court also considered that the own name defence would be available to a partnership, on the same basis as for individuals: So also the defendants would be entitled to carry on such a business in partnership, and to adopt as a firm-name a combination of their individual names. For any confusion unavoidably resulting from such an exercise of their right to trade under their own names they would not be answerable.10 However, Salmond J held that the defence was not available to an incorporated company, particularly in circumstances where the name was calculated to deceive (as his Honour had found earlier in the case): The deception of which [the plaintiff] company complains is not such deception as is an inevitable incident of the defendant’s [sic.] right to trade as carriers under their own names; it is a deception which is the result of the voluntary choice by the defendants of an invented title which contains a mere abbreviation of their name.11 The Court therefore held that the own name defence would be available to an individual or partnership facing a claim for passing off, provided that there was no intention to deceive, although the defence was unlikely to be available to companies. The own name defence to passing off first began to emerge in England with the High Court’s decision in Joseph Rodgers & Sons Limited v W N Rodgers & Co:12 It is the law of this land that no man is entitled to carry on his business in such a way as to represent that it is the business of another, or is in any way connected with the business of another; that is the first proposition. The second proposition is, that no man is entitled so to describe or mark his goods as to represent that the goods are the goods of another. To the first proposition there is, I myself think, an exception: a man, in my opinion, is entitled to carry on his business in his own name so long as he does not do anything more than that to cause confusion with the business of another, and so long as he does it honestly.13 The own name defence to passing off was definitively rejected in South Africa in BoswellWilkie Circus Pty Limited v Brian Boswell Circus Pty Limited.14 In that case, Didcott J referred to the own name exception as “an exception [which the Judges who formulated the test of passing-off] overlooked which rather spoils the rule’s symmetry.”15 The Court embarked upon a comprehensive survey of the relevant English cases, and came to the following conclusion: My survey of the authorities brings me to the conclusion that the law recognises no exception to the prohibition against passing off which can be invoked successfully in the present litigation, no exception which protects a man’s use of his own name when, had it not in truth been his, its exploitation by him would have amounted to passing off that was actionable. The judgments lending colour to the proposition that such an exception exists in some shape or another are confined, one discovers when one goes through the gamut, to a handful. It is questionable whether a number which seem at first to support the proposition have that effect after all, while those that do are vulnerable to criticism and in subsequent cases have received it.16 10 At 209. At 209. 12 (1924) 41 RPC 277. 13 Ibid, at 291. 14 [1985] FSR 434; affirmed at [1986] FSR 479. 15 At 444. 16 At 470-1. 11 3 In the subsequent New Zealand High Court case of Taylor Bros Limited v Taylors Group Limited,17 McGechan J reviewed the relevant authorities and proceeded on the basis that the own name defence was available to an action for passing off. 18 However, the Court found that the defendant had failed to make out the defence because it was not trading under the precise company name which has been registered. His Honour also suggested that the defence might fail in any event because use of the name would cause confusion and possibly deception. Cooke P referred to the defence in relation to passing off in delivering the Court of Appeal’s unanimous decision in the Taylor Bros appeal:19 The so-called “own name” exception in the law of passing off is of controversial extent, especially as regards companies. there is a review of the case law by Somers J in the Supreme Court, as the High Court then was, in New Zealand Farmers Co-Operative Association of Canterbury Ltd v Farmers Trading Co Ltd (1979) 1 NZIPR 212. Nothing in the cases persuades us that a company is entitled to start business in a new area using an adaptation of its registered name which misleads customers into assuming that it is associated with an established company enjoying a distinctive reputation there.20 There is no own name defence to proceedings under the Fair Trading Act in New Zealand. In Neumegen v Neumegen & Co21 the Court of Appeal rejected the possibility of an “own name” of defence to action for breach of the Fair Trading Act, and all but excluded the availability of the defence to an action for passing off in New Zealand. The Court held: [C]ertainly under the Fair Trading Act and very likely as well under the tort of passing-off (Boswell-Wilkie Circus (Pty) Ltd v Brian Boswell Circus (Pty) Ltd [1985] FSR 434), there is no “own name” exception. Paterson J accurately concluded that if what Peter and Mark Neumegen proposed to do is deceptive and misleading in terms of s 9, they are not assisted by the fact that the proposed firm name includes their surnames.22 The majority in Neumegen v Neumegen also observed the importance of secondary meanings which members of the public might attach to brand names: However, there will be no misrepresentation by means of the adoption of a trading name unless the name has already acquired a reputation amongst a class of consumers as denoting the goods or services of another trader, so that members of that class will be likely mistakenly to infer that the goods or services are connected with the business of that other trader. … The more unusual the name, the more likely it will be that its use by another trader has given rise to a secondary signification.23 In summary, the own name defence to passing off is inconsistent with the conceptual basis of the tort. Even if an own name defence to passing off exists, it is highly unlikely that such a defence would be available to companies in New Zealand. 17 [1988] 2 NZLR 1. For commentary on the New Zealand position, see also NZ Farmers Co-operative Association of Canterbury Limited v Farmers Trading Co Limited (1979) 1 NZIPR 213. 19 [1998] 2 NZLR 1, 33 at 38. 20 At 38. 21 [1998] 3 NZLR 310. 22 At 317. Thomas J dissented from the judgment given by Blanchard J on behalf of Richardson P and Blanchard J. Thomas J, however, did not suggest the availability of an own name defence to proceedings under the Fair Trading Act. 23 At 317. 18 4 Sections 12(a) and 13 of the Trade Marks Act 1953 Section 12(a) of the Trade Marks Act 1953 provides a defence to trade mark infringement where a person simply uses their own name in good faith. Specifically, the section states: 12 Saving for use of name, address, or description of goods or services No registration of a trade mark shall interfere with— (a) Any bona fide use by a person of that person's own name or of the name of that person's place of business, or of the name, or of the name of the place of business, of any of that person's predecessors in business;… Section 13 provides: 13 Infringement by use of name of company In an action for infringement of a trade mark it shall not of itself be a defence that the infringement arose from the use of the name under which a company has been registered. At first glance, section 13 appears to deny the section 12(a) “defence” (in the loose sense of the word) to companies.24 As will be seen, however, in Anheuser Busch the majority of the Court of Appeal declined to adopt this straightforward interpretation, as it would make redundant the words “of itself”, and held that those words were intended to make it clear that registration and use of a company name did not provide an absolute defence to infringement. Before analysing the Court of Appeal’s construction further it is necessary to delve into the history of that section, as this historical context was crucial to the majority’s interpretation of the section. Background to the insertion of section 13 As noted above, section 13 was enacted in response to the recommendations made in the Evans Commission report. The mischief the Evans Commission was concerned to remedy was the fact that a company could be registered under a name comprising or incorporating the registered trade mark of a third party. The Evans Commission recommended that one or other of two options be enacted to address this concern: 324. One recommendation which we desire to make relates to the possibility of greater co-operation between the Registrar of Companies and the Commissioner of Patents. At the present time it is possible for a company to be registered having as an essential part of its name the registered trade-mark of another person. Once a company is registered it is necessary for any person aggrieved thereby to seek an appropriate remedy in the Supreme Court, with the attendant expense. 325. We recommend either or both of the following provisions: 24 The UK position is uncertain even in the absence of an equivalent provision to section 13, as noted by Jacob J in Hart v Relentless Records Limited [2002] EWHC 1984 (Ch): “[T]here is the unresolved question of whether or not the defence applies to companies as opposed to individuals. According to the House of Lords in Scandecor Development v Scandecor Marketing [2002] FSR 122, the better view is that it applies to both but that the point is not certain. The House referred the question to the ECJ but the case has settled.” (para 83). 5 (a) That the Patents, Designs and Trade-marks Act be amended to provide that the use of a registered trade-mark or a word so closely resembling same as to be calculated to deceive or cause confusion as part of the name of a limited liability is such a use as would constitute an infringement of the registered trade-mark under section 6, subsection (1), of the Patents, Designs and Trade-marks Amendment Act, 1939. (b) That the Companies Act, 1933, be amended to provide that the Registrar or Companies may refuse to register any company (i) The name of which comprises a registered trade-mark or a word so closely resembling the same as to be calculated to deceive or cause confusion; and (ii) The main trading object or objects of which include manufacturing or vending foods covered by such registered trade-mark, and to that end he should cause a search to be made in the Register of Trade-marks before registering a company in a name which is or contains a word or words capable or registration as a trade-mark. We think that it undesirable to make it mandatory for the Registrar of Companies to refuse to register a company under the circumstances set forth in this paragraph because in some cases it is possible that the registered trademark may cover goods in respect of which it has never been used. Although these were expressed as alternatives, both the trade marks and companies statutes were in fact amended. The recommendations were implemented in the Trade Marks Act 1953 and the Companies Act 1955 respectively.25 However, the amendment in respect of the trade mark legislation (section 13) was not enacted in the manner recommended by the Evans Commission. The legislature did not simply state that registration of a company name incorporating a third party’s trade mark constituted trade mark infringement. The question of exactly what section 13 was intended to achieve took nearly 50 years to come before the Courts. Interpretation Act 1999 Section 4 of the Interpretation Act 1999 sets out the application of the Act generally: 4 Application (1) This Act applies to an enactment that is part of the law of New Zealand and that is passed either before or after the commencement of this Act unless— (a) The enactment provides otherwise; or (b) The context of the enactment requires a different interpretation. 25 See sections 31(3) and 32(2)(b) of the Companies Act 1955. New Zealand’s companies legislation no longer creates a positive obligation upon the Registrar of Companies to make enquiries in relation existing trade mark registrations prior to registration of a company name: see section 22 of the Companies Act 1993. Sections 31(3) and 32(2)(b) of the 1955 Act were repealed by the Companies Amendment Act (No 2) 1983 from 6 December 1983. Since that time, the Companies Office’s modified practice has been that when it grants name approval for a company registration it makes no search of any intellectual property databases, such that it is now well known and accepted that registration of a company name of itself can give no proprietary rights and cannot be taken as an indication that registration alone does not infringe a third party’s proprietary rights. 6 (2) The provisions of this Act also apply to the interpretation of this Act. Historically, matters such as the place where a section appears in an act were not strictly relevant to statutory interpretation. This has changed under the Interpretation Act 1999, which now requires the Courts to pay attention to matters such as a placement of a section within an Act:26 5 Ascertaining meaning of legislation (1) The meaning of an enactment must be ascertained from its text and in the light of its purpose. (2) The matters that may be considered in ascertaining the meaning of an enactment include the indications provided in the enactment. (3) Examples of those indications are preambles, the analysis, a table of contents, headings to Parts and sections, marginal notes, diagrams, graphics, examples and explanatory material, and the organisation and format of the enactment. As noted earlier, section 12 of the Trade Marks Act 1953 refers to the conduct of “persons”, without expressly stating whether the section was intended to apply to companies. Section 30 of the Interpretation Act 1999 contains definitions to assist interpretation of a statute where defined terms are so used: 30 Definitions in enactments passed or made before commencement of this Act In an enactment passed or made before the commencement of this Act,— … Person includes a corporation sole, and also a body of persons, whether corporate or unincorporate. Section 4 of the Acts Interpretation Act 1924 formerly provided: 4 General Interpretation Of Terms In every Act of the General Assembly or of the Parliament of New Zealand, if not inconsistent with the context thereof respectively, and unless there are words to exclude or to restrict such meaning, the words and phrases following shall severally have the meanings hereinafter stated, that is to say: … Person includes a corporation sole, and also a body of persons, whether corporate or unincorporate: Section 30 of the Interpretation Act 1999 does not contain the same caveat found in the equivalent provision of the 1924 Act, which makes it clear that the definition of “Person” is essentially a default provision. While on its face section 30 would appear to apply to all references to a “Person”, in reality section 5 of the Interpretation Act would also apply such 26 Cooke P used similar reasoning to assist in interpreting the State-Owned Enterprises Act 1986 in New Zealand Maori Council v Attorney-General [1987] 1 NZLR 641, 658. 7 that it is open to a Court to disregard the default position if the enactment provides otherwise or the context of the enactment requires a different interpretation. Anheuser Busch Inc v Budweiser Budvar National Corporation Anheuser Busch Inc v Budweiser Budvar National Corporation was the New Zealand extension of trade mark and trade name battles being fought between the parties in a number of countries. To briefly summarise the facts of the case, American brewer Anheuser Busch (AB) was the registered proprietor of, inter alia, the trade marks BUDWEISER and BUD in New Zealand in respect of beer. AB had imported and sold beer in New Zealand under those trade marks since at least 1980. Budweiser Budvar (BB), a rival brewer from the Czech Republic, began importing beer into New Zealand with the words BUDĚJOVICKÝ BUDVAR on the label in 1996. The label stated that BB’s products were brewed and bottled by BUDWEISER BUDVAR. AB sued BB (and BB’s New Zealand distributor) for trade mark infringement of its BUD and BUDWEISER marks, specifically for use of the words “BUDWEISER”, “BUDĚJOVICKÝ” and “BUDVAR”. In the High Court,27 Doogue J decided in favour of BB, although His Honour did not consider the application of section 13 in detail: I am surprised at the submission that the first defendant’s use of “Budweiser Budvar” was not by a “person”. I appreciate there is a distinction between s 12, which refers to “person” and s 13, which refers to “a company”, but it has never previously been suggested that the use of the word “company” in s 13 excludes the normal meaning of the word “person” in s 12 as including an individual or a company: see, for example, Parker-Knoll Ltd v Knoll International Ltd [1962] RPC 265.28 Doogue J also relied upon the definition of “person” contained in section 29 of the Interpretation Act 1999, which provides that the word “includes a corporation sole, a body corporate”.29 On that basis, the Court concluded that the own name defence contained in section 12(a) was available to companies. How the Court of Appeal interpreted section 13 On appeal, Gault P delivered the leading judgment of the Court, with McGrath and Glazebrook JJ concurring except in respect of the correct application of section 13. McGrath and Glazebrook JJ delivered a joint judgment on this point, with Gault P dissenting. The Court essentially agreed as to the purpose of the amendments to the trade marks and companies legislation, although the judges disagreed on the effect of those amendments. As Gault P observed: It is clear to me that the legislative intention at the time was to give effect to the recommendations that the companies should not trade in goods covered by a trade mark registration under a name comprising the registered trade mark, and could be required to change offending names. What is less clear is whether the provisions of the Trade Marks Act manifest that intention, given the wording of s13 and its relationship to s12(a). It is couched not as a statement of what infringes, but as an exclusion of a defence.30 27 Reported at [2001] 3 NZLR 666; (2002) 53 IPR 641. Para 86. 29 Section 29 contains an identical definition of “person” to that found in section 30, although section 30 is specifically expressed to apply to enactments passed or made before the commencement of the Interpretation Act 1999. 30 Para 114. 28 8 Gault P took the view that section 13 was intended to deprive companies of the benefit of section 12(a). The President differed from the High Court in considering that the context of the legislation dictated that section 29 of the Interpretation Act 1999 should not apply to section 12(a). Gault P further reasoned that the words “of itself” simply indicated that companies were still entitled to avail themselves of the other defences in the Trade Marks Act 1953, such as prior continuous use (section 11(2)) or that the mark was not used as a trade mark (although this is simply an argument that a relevant aspect of the cause of action is missing, rather than being a separate defence per se). The reasoning of the majority is more complicated. The majority held that section 13 was not intended to deprive companies of the benefit of section 12(a). Their Honours surmised that the aim of section 13 was for the legislature to put it beyond doubt that registration of a company under a name containing a trade mark does not in itself constitute a defence. This is where, with respect, the reasoning of the majority becomes less convincing. Their Honours were plainly troubled by the (quite compelling) argument that if Parliament had intended section 12(a) to have no application to companies, it would have said so in clear, unequivocal language. This could have been achieved by amending section 12, or “by otherwise making the interrelationship between the two provisions clear”.31 Accordingly, the majority felt bound to ascribe some meaning to section 13 other than that which Gault P had found. The majority suggested that the purpose of section 13 was to counteract any suggestion which could arise from the amendment to the Companies Act (not yet enacted when the Trade Marks Act was passed) that the registration of a company under a name containing a trade mark does not of itself constitute a defence. McGrath and Glazebrook JJ held: Anticipating perhaps in 1953 that the recommendation in para 325(b) would also be adopted, and the Registrar of Companies given a new power to refuse registration of a name comprising a registered trade mark, Parliament apparently felt it necessary to counter any suggestion that, if the Registrar allowed registration, that was in itself a defence.32 The majority’s decision is open to criticism, both for the manner in which the Judges ascertained Parliament’s intention and for the actual substantive decision as to the proper meaning of section 12(a). Determining parliamentary intent is a challenging task for the courts at the best of times. It is particularly difficult in circumstances where Parliament’s rationale in departing from the exact recommendations of the Evans Commission is unarticulated and unclear. McGrath and Glazebrook JJ accepted as much in their judgment.33 McGrath and Glazebrook JJ’s analysis of parliamentary intent assumes that Parliament would have been aware of future amendments to the companies legislation when it passed the Trade Marks Act 1953. This might be understandable if the Bills were being passed contemporaneously, but in fact the amendments to the companies legislation were not enacted until two years later. Moreover, the Companies Act 1955 was eventually enacted by a subsequent Parliament (elected in 1954) to that which had passed the Trade Marks Act 1953. Clearly the argument that Parliament had such clarity of foresight would be unconvincing if the Companies Act had not in fact been amended along the lines recommended by the Evans 31 Para 144. Para 149. 33 Their Honours said that they had been unable “to locate anything in the Parliamentary debates or elsewhere that explains the change in approach or the purpose behind the current form of s13”: para 149. 32 9 Commission, but whether or not those amendments were enacted is strictly irrelevant to the majority’s analysis of Parliament’s intent in 1953. Discussion of sections 12(a) and 13 of the 1953 Act In addition, the substance of the decision that section 12(a) applies to companies just as to natural persons is also unsound. The issue upon which the majority in Anheuser Busch and Doogue J disagreed with Gault P was essentially whether the context of the Trade Marks Act 1953 required a different interpretation of the word “person” in section 12(a) from the definition contained in section 29 of the Interpretation Act. Section 12(a) of the Trade Marks Act itself is neutral in this regard; there is nothing in the section to indicate that it should apply solely to natural persons, although neither does it contain anything to suggest that it necessarily does apply to companies. The proper construction based on section 5 of the Interpretation Act, however, is that section 12(a) should be interpreted as subject to section 13, and/or that the reference to “person” in section 12(a) should be read as meaning natural persons only (thereby excluding companies). Section 5 of the Interpretation Act 1999 requires that consecutive sections be read together, on the basis that the location of a section within an enactment is an indication of parliamentary intent. As such, sections 12 and 13 should be read together and treated as dealing with the same subject matter in the absence of any further indication to the contrary contained in the Act. The fact that the sections are contained in the same sub-Part of the Act (dealing with “Effect Of Registration, And The Action For Infringement”) is also highly relevant. On this approach the only option for the sections to interpreted consistently with each other is for section 12(a) to be read as subject to section 13, essentially implying the words “Subject to section 13 of this Act” into the start of section 12. Any other interpretation of section 13 disregards its proximity to section 12, and fails to give that point the importance required when in interpreting section 12(a) under the Interpretation Act. The alternative option (favoured by the majority of the Court of Appeal) is in essence that sections 12 and 13 deal with different matters. In that case, section 13 would be given a narrow meaning and be viewed as simply confirming that registration and use of a company name does not provide an absolute defence to trade mark infringement.34 That argument, however, would appear to ignore the effect of section 5 of the Interpretation Act 1999, as it does not take account of the fact that sections 12 and 13 are consecutive and contained in the same sub-Part of the Act. McGrath and Glazebrook JJ’s conclusion on section 13 dilutes the effect of the provision to the point where it is all but meaningless. According to the majority of the Court, the only consequence of section 13 is that a defendant cannot claim that its successful registration of a company name provides a defence to trade mark infringement. However, in light of the fact that the Registrar no longer has a positive obligation to undertake trade mark searches prior to registering company names (and, crucially, did not have such a power in the intervening two years between the enactment of the Trade Marks Act 1953 and the Companies Act 1955), it is difficult to imagine a defendant could successfully raise that argument in any event. In the absence of any real administrative control over what names may be registered as company 34 This reasoning was applied in Telecom Corporation of New Zealand Limited & Anor v Chinese Yellow Pages (CL23/02, Wellington; Williams J; 18 November 2002) at para 38: “[T]he fact that [the defendant company] has achieved incorporation under a name including the words of Telecom’s YELLOW PAGES® trade mark does not of itself give it a defence to an application for a declaration that titling its publication “Chinese Yellow Pages” infringes Telecom’s YELLOW PAGES® trade mark. Its use of the name under which it is incorporated in its publication “Chinese Yellow Pages” is accordingly of assistance to it but is not the complete answer to the claim.” 10 names, it is difficult to see that any moral claim to a third party’s trade mark could be established simply by registering that trade mark as or as part of a company name. McGrath and Glazebrook JJ’s construction is less convincing than simply excluding companies from the section 12(a) defence, since it rests on Parliament’s intention in enacting the statute being to debar the own name defence in circumstances where the defence would not appear to be strong (or even arguable) in the first place. In addition to being the preferable interpretation of the relevant sections on a statutory interpretation basis, exclusion of the own name defence for companies is also justified on policy grounds. There are limits on the names which traders can use to distinguish their goods and services. Those limits exist to ensure that members of the public are not deceived by identical or confusingly similar names, and also have the effect of protecting goodwill of existing traders. As noted by Lord Herschell in Reddaway v Banham in relation to passing off, there are plainly cases where a secondary meaning arises in the minds of members of the public from use of a particular trade name. This is the rationale for the exclusion of the own name defence, in passing off at least. The own name defences to trade mark infringement and passing off appear to have developed out of sympathy for the plight of a trader who cannot simply start a business under their own name, such as the “John Brown the grocer” example which Salmond J offered by way of illustration in JJ Craig Limited v A E Craig and H R Craig.35 While on that level the defence seems to be fair and commonsense, the fact that there might be a legitimate reason for the use of a particular name (being the person or company’s own name) does not mean that the Court should ignore the secondary meaning in circumstances where confusion has arisen or is likely to arise and the plaintiff would otherwise be entitled to relief. This perhaps provides a further possible meaning of sections 12(a) and 13 of the Trade Marks Act 1953: that in spite of the apparent logic of an own name defence, such a defence is not available to companies facing proceedings for trade mark infringement. It is possible that this was Parliament’s intention in enacting section 13 of the Trade Marks Act, to ensure that the own name defence protected individuals and partnerships, but did not apply to companies trading under “invented” names. This would have led to consistency between trade mark law and the law of passing off (at least as stated by the New Zealand Supreme Court). Such consistency is obviously not essential, but the logic which would exclude the own name defence in passing off (certainly in relation to companies) is equally applicable to the own name defence to trade mark infringement. The proper construction of sections 12(a) and 13, based on statutory interpretation and policy grounds, would therefore be to prevent companies from using the own name defence to trade mark infringement. What will happen to the “own name” defence under the Trade Marks Act 2002? The words “of itself” have disappeared from the section which will replace section 13 when the Trade Marks Act 2002 comes into force later this year: 91 No defence that infringement arose from use of company name In an action for infringement of a trade mark, it is not a defence that the infringement arose from the use of the name under which a company has been registered. 35 [1922] NZLR 199, 206-7, as referred to above. 11 As with its counterpart from the 1953 Act, however, the section operates to exclude a possible defence, rather than to expressly provide that registration of a company name amounts to trade mark infringement. The replacement for section 12 of the 1953 Act is section 95 of the 2002 Act, which is based upon section 28(1) of Singapore’s Trade Marks Act 1998.36 95 No infringement for honest practices A person does not infringe a registered trade mark if, in accordance with honest practices in industrial or commercial matters, the person uses-(a) the person's name or the name of the person's place of business; or (b) the name of the person's predecessor in business or the name of the person's predecessor's place of business; or (c) a sign to indicate-(i) the kind, quality, quantity, intended purpose, value, geographical origin, or other characteristic of goods or services; or (ii) the time of production of goods or of the rendering of services. While the amendments will provide the Court of Appeal with an opportunity to revisit its precedent as to the availability of the own name defence to trade mark infringement for companies, it remains possible that Anheuser Busch will continue to apply even under the 2002 Act. It may be that the Court will see fit to revisit the issue and assess Parliament’s intention in passing the relevant provisions in the new Act. In particular, Parliament’s intention on this point may differ between the Trade Marks Act 1953 and the new Act based on the fact that the Registrar of Companies no longer has a positive obligation under companies legislation to conduct trade mark searches prior to registering company names, which was a material if not crucial aspect of the majority’s reasoning. However, although the majority’s reasoning is probably less convincing in light of the amendments, there is nothing express in the wording of the Act to displace the current position that section 13 of the 1953 Act (or section 91 of the 2002 Act) does not override section 12(a) (section 95). The future application of Anheuser Busch in this regard is therefore uncertain. Practical implications of the Anheuser Busch case There is unlikely to be a great deal of difference in the practical terms between the majority’s decision in Anheuser Busch and the position if the Court had reached the same conclusion as Gault P on the relationship between sections 12(a) and 13. It may well be that the formal availability of the own name defence to trade mark infringement by companies is not important in substance, since a company defendant will still need to show that its use of its own name was bona fide (under section 12(a) of the 1953 Act, while it remains in force) or, under section 95 of the 2002 Act, in accordance with honest practice in industrial or commercial matters. Certainly in the Anheuser Busch and Advantage cases, the Court of Appeal held in both cases that the uses of their own names by the defendants were 36 Also compare with section 11(2) of the Trade Marks Act 1994 (UK). 12 not bona fide, and the defences failed on this basis.37 In individual cases, much will therefore depend on the Court’s assessment of the manner in which the name is being used. Equally, the main category of cases to have been affected if Gault P’s judgment were adopted would be where the company has used its own name in good faith since prior to the defendant doing so, although the defence of prior continuous use would be more logically applicable in such situations in any event. Conclusion The Trade Marks Act 2002 would appear to exclude more clearly the “own name” defence to trade mark infringement for companies than section 13 of the Trade Marks Act 1953, as it omits the words “of itself” which caused so much interpretative difficulty. Even so, there is no guarantee that in the future the Courts will overturn the majority’s finding in Anheuser Busch v Budweiser Budvar. As such, the own name defence appears to be available for companies in New Zealand in formal terms, subject to the practical point that it may well be more difficult for a company with an invented name to make out the “bona fide” aspect of the defence. 37 There is a substantial body of English case law relating to the whether the use of the name has been bona fide. The leading cases are Baume & Co Limited v A H Moore Limited [1957] RPC 459, [1958] RPC 226; Steiner Products Limited v Willy Steiner Limited [1964] RPC 356; Ballantine & Sons Limited v Ballantyne Stewart & Co Limited [1959] RPC 273; Provident Financial plc v Halifax Building Society [1994] FSR 81. The test for whether the name is being used bona fide is subjective: Mercury Communications Limited v Mercury Interactive (UK) Limited [1995] FSR 850. There is also English case law on the extent to which a defendant must use its own name exactly to avail itself of the defence: Baume & Co Limited v A H Moore Limited [1957] RPC 459, [1958] RPC 226; Parker-Knoll International Limited v Knoll International Limited [1962] RPC 243. See also Eady v Lewis R Eady & Son Limited [1920] NZLR 636. 13