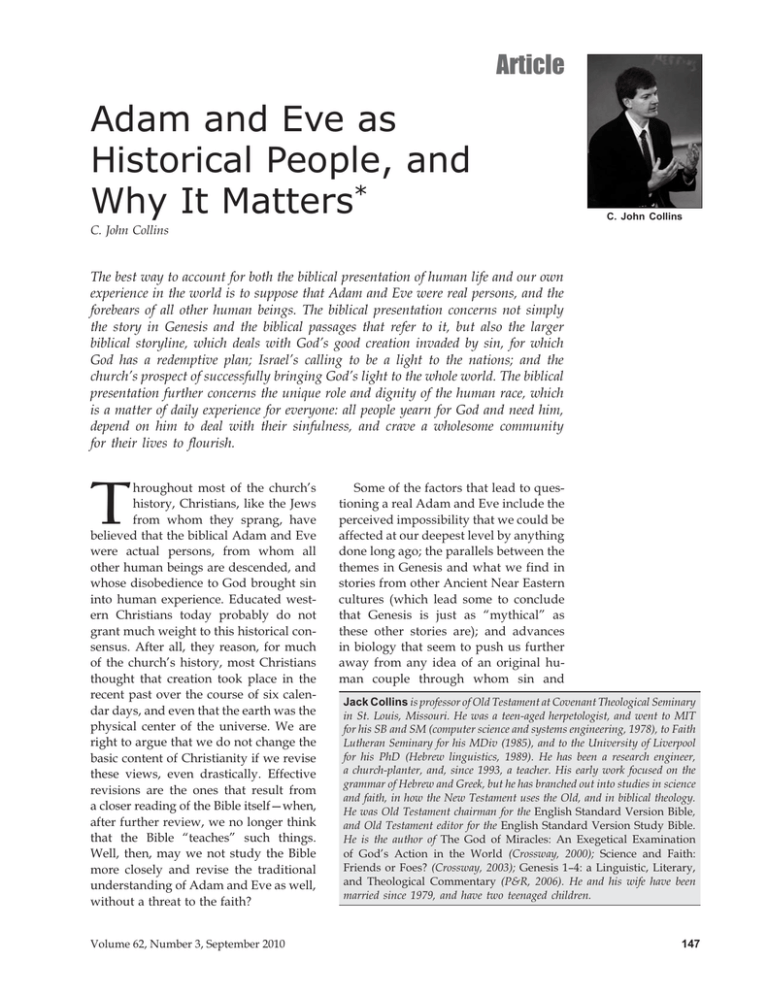

Adam and Eve as Historical People, and Why It Matters

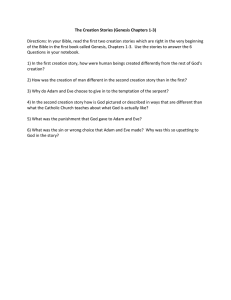

advertisement