GMP and GDP: a review of regulatory inspection findings and

advertisement

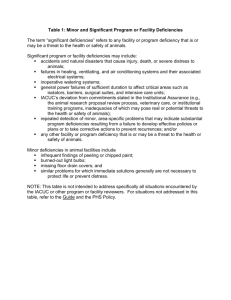

For personal use only. Not to be reproduced without permission of the editor (permissions@pharmj.org.uk) Articles GMP and GDP: a review of regulatory inspection findings and defective medicines reports for 2004–05 The purpose of this article is to indicate to manufacturers and distributors areas on which they may wish to focus their training programmes, internal audit and quality improvement, in order to increase their compliance with Good Manufacturing Practice and Good Distribution Practice his article reports the nature and frequency of serious deficiencies in compliance with Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP) and Good Distribution Practice (GDP) found on regulatory inspections by the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) during the year 2004–05. It covers industrial manufacturing and distribution sites in the UK, manufacturing sites in third countries and sites where the NHS is the licence holder. Data for the years 1996–97,1 1998–992 and 2001–023 were published previously. The paper also reviews reports of defective medicines received by the MHRA’s Defective Medicines Report Centre (DMRC) and drug alerts issued in 2005 to support recalls issued by the relevant importers, manufacturers and marketing authorisation holders. T Method The authors Deficiencies reported in this article are those categorised as “critical” or “major” in the report to the licence holder; other deficiencies, often minor, are not considered here. Critical deficiencies are those that indicate a significant risk that a product could or would be harmful to a patient, or a deficiency that has produced a harmful product. A combination of major deficiencies that indicates a critical systems failure may also be classed as critical. Major deficiencies are those non-critical deficiencies that could or would produce a product not in compliance with its marketing authorisation, those that contravene the provisions of a manufacturing authorisation or wholesale dealer’s licence to a significant exJohn Taylor, FRSC, is the quality and standards manager of the MHRA’s inspection and standards division and enforcement and intelligence group, Gerald Heddell, MIBiol, is director of the inspection and standards division, Ian Holloway, MRPharmS, is the head of the Defective Medicines Report Centre, Graham Matthews, MRPharmS, is a pharmaceutical assessor in the DMRC and Ian Rees, MRCVS, is a senior GMP inspector Correspondence to: John Taylor, Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency, Market Towers, 1 Nine Elms Lane, London SW8 5NQ www.pjonline.com Table 1: Deficiencies per inspection for UK and third country sites in successive years Year UK manufacturers (including NHS) Third country manufacturers 99–00 00–01 01–02 02–03 03–04 04–05 2.2 3.4 1.8 3.2 1.4 4.8 1.6 2.8 1.3 2.2 1.5 2.2 tent and those that relate to a Qualified Person or Responsible Person failing to carry out his or her obligations. A major deficiency is also indicated if relevant changes in premises, production, processes or controls have not been notified to, or agreed by the licensing authority, or if there is a significant departure from GMP or GDP not covered by the above categories. Data concerning critical and major deficiencies (reported collectively as “serious” deficiencies) reported below are derived from inspection reports issued in 2004–05. To inform the analysis each deficiency is assigned to one of 40 categories. Comparisons are made between findings in different sectors, ie, UK industrial manufacturers, UK NHS manufacturers and third country industrial manufacturing sites. Serious GDP deficiencies recorded at wholesale distributors are also considered. Findings Analysis of GMP deficiencies for 2004–05 Data from inspections in 2004–05 of UK manufacturers (including NHS sites) and third country (ie, non-EU or non-EEA) manufacturers were analysed.The numbers of serious (ie, critical and major) deficiencies recorded per inspection in each sector were 1.50 for UK sites, 1.57 for NHS sites and 2.23 for third country sites. As for the previous years since analysis began in 1994, more deficiencies were recorded per inspection of third country sites than UK sites. Comparative figures for the past five years are shown in Table 1.The number of deficiencies per inspection for UK industrial sites and NHS sites has remained relatively constant for the past four years, and the number of deficiencies per inspection for third country manufacturing sites has also fallen. Table 2 shows the categories and the number of GMP deficiencies most frequently reported in 2004–05 for all sectors. These represent 79 per cent of the total number. Table 2: Most frequently reported GMP deficiencies in 2004–05 in all sectors Category of GMP deficiency Quality management Batch release and duties of the QP Quality system documentation Potential for microbial contamination Evidence of compliance with TSE guidelines Design and maintenance of premises Environmental monitoring Process validation Potential for non-microbial contamination Cleaning validation In-process control and monitoring of production operations Validation documentation Line clearance, segregation and potential for mix-up Handling and control of packaging components Starting material and packaging component testing Warehousing and distribution activities Complaints and product recall Design and maintenance of equipment Manufacturing documentation Training Incidence (%) 8.0 5.9 5.9 5.0 4.6 4.6 4.6 4.6 3.8 3.8 3.8 3.8 3.4 3.4 2.5 2.5 2.1 2.1 2.1 2.1 In the previous two years, concerns related to the potential for non-microbial contamination headed the overall list of deficiencies. The incidence of citations in this category was 8.2 per cent of the total number in 2002–03, falling to 6.8 per cent in 2003–04 and to 3.8 per cent in 2004–05. The highest number of deficiencies per inspection in 2004–05 concerned quality management. Data for the past two years show a rise in deficiencies in this category from 14th spot in 2002–03 to third spot in 2003–04 to top spot last year (Table 2). However, non-compliances relating to the potential for all types of contamination were the most frequent reason for recording a deficiency last year. 20 May 2006 The Pharmaceutical Journal (Vol 276) 593 Articles Tables 3, 4 and 5, respectively, show the top 10 categories of deficiency reported during inspections of UK industrial manufacturers, NHS manufacturers and third country manufacturers in 2004–05, ranked in descending order of incidence, compared with rankings for the previous three years. Gaps in the tables indicate that the particular category did not appear in the top 20 in a particular year. For UK industrial sites (Table 3) deficiencies related to quality management wer the main concern last year. Concerns over batch release and duties of the Qualified Person and quality system documentation continue to feature prominently. For NHS manufacturers (Table 4) deficiencies related to validation documentation form the highest category.This is a new category for the deficiency analysis, deficiencies concerning validation documentation having previously been assigned to other validation categories. Concerns related to the design and maintenance of manufacturing facilities at NHS sites continue to feature prominently and there appears to be a trend towards increasing incidence of deficiencies related to quality system documentation. Potential for microbial contamination continues to cause concern. For third country manufacturers concerns related to potential for microbial contamination continue to dominate the analysis (Table 5). The proportion of reports of deficiencies related to in-process control and monitoring of production operations continues to feature prominently and deficiencies related to finished product testing are increasing. Lack of evidence to demonstrate compliance with guidelines related to transmissible spongiform encephalopathy (TSE) is an increasing concern for UK and third country industrial manufacturers. Analysis of GDP deficiencies for 2004–05 The number of serious deficiencies per inspection reported from visits to wholesale distributors continues to show a downward trend. Serious GDP deficiencies per inspection were 1.34 in 1999–2000, 0.98 in 2000–01, 0.94 in 2001–02, 0.97 in 2002–03, 0.63 in 2003–04 and 0.38 in 2004–05. Table 6 shows the GDP deficiencies cited most frequently in 2004–05 in descending order of ranking, compared with their rankings in the previous four years. A dash against a category indicates that it did not appear in the top 20 categories in that particular year. For the past four years the largest number of deficiencies have concerned the control and monitoring of storage conditions in general warehouse areas (as opposed to cold stores). Overall, deficiencies related to the control and monitoring of storage and transportation temperatures of medicines comprised 43 per cent of the total number of serious deficiencies. There was an increase in the incidence of reports of unauthorised activities. Deficiencies concerning returns (including returns of cold chain goods) have increased in prominence. 594 The Pharmaceutical Journal (Vol 276) 20 May 2006 Table 3: Trends in the top 10 categories of deficiency for UK industry Category of deficiency Quality management Batch release and duties of the QP Quality system documentation Design and maintenance of premises Environmental monitoring Process validation Evidence of compliance with TSE guidelines Cleaning validation Potential for microbial contamination Potential for non-microbial contamination Ranking by year 01–02 02–03 03–04 04–05 17 15 4 3 – 10 12 – 13 1 17 4 1 9 12 6 – 20 10 2 3 1 6 13 – 12 – 17 – 4 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Table 4: Trends in the top 10 categories of deficiency for NHS sites Category of deficiency Validation documentation Design and maintenance of premises Quality system documentation Potential for microbial contamination Environmental monitoring Sterility assurance Batch release Failure to respond to previous inspection findings Potential for non-microbial contamination Design and maintenance of equipment Ranking by year 01–02 02–03 03–04 04–05 – 1 8 2 4 12 13 – 6 14 – 1 5 2 3 10 11 19 15 8 – 2 3 4 13 14 17 11 8 18 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Table 5: Trends in the top 10 categories of deficiency for third country manufacturers Category of deficiency Potential for microbial contamination Evidence of compliance with TSE guidelines Validation documentation In-process control and monitoring of production operations Potential for non-microbial contamination Batch release Cleaning validation Equipment validation Finished product testing Handling and control of packaging components Ranking by year 01–02 02–03 03–04 04–05 8 6 – 2 15 – 2 13 – 1 2 3 1 2 – 18 10 – 17 8 1 – 7 – – 9 3 1 – 10 7 18 12 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Discussion Manufacturers Serious deficiencies reported by the MHRA’s medicines inspectors from inspections of UK and third country manufacturers have shown a number of trends in recent years. Inspectors’ concerns related to quality management have come to the fore for UK industrial manufacturers, while deficiencies related to batch release and duties of the Qualified Person continue to cause concern. Corrective action concerning quality system documentation remains a priority for manufacturers and there appears to be an increasing incidence of deficiencies regarding cleaning validation. Deficiencies related to the potential for non-microbial contamination show a decreasing trend that may reflect increasing attention paid to this area by UK industry. Handling and control of packaging components did not feature in the top 10 in 2004–05, although defects related to packaging, labels and leaflets continued to comprise the most common reason for batch recall in the UK. A number of hospitals and NHS trusts in the UK hold manufacturer’s specials licences which authorise the manufacture of unlicensed medicinal products to fulfil special clinical needs.These facilities are inspected at the same frequency and to the same standards as UK industrial manufacturers and it is, therefore, not surprising that similar categories of deficiency are recorded in each sector.The main differences seen in the data for 2004–05 are in the categories of validation documentation, sterility assurance and failure to respond to previous inspection findings, which do not appear in the top 10 for UK industry. The latter category of deficiency shows an increasing trend for NHS manufacturing facilities. www.pjonline.com Articles Table 6: Trends in the most frequently reported GDP deficiencies Description of deficiency Ranking by year 00–01 01–02 02–03 3 4 1 – 2 8 – 13 9 5 1 4 3 – 2 10 – 17 7 6 1 11 2 – 3 5 7 – 4 6 General storage — temperature control and monitoring Returns Lack of or inadequate written procedures Unauthorised activity Cold storage — temperature control and monitoring Housekeeping and pest control Cold chain transportation Customer status Premises, equipment and calibration Duties of Responsible Person Table 7: Most frequently reported GMP deficiencies in 2004–05 for IMP sites Category of GMP deficiency Incidence (%) 1 7 2 – 4 6 8 – 3 5 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Vaccine (%) All (%) 14.3 14.3 10.7 7.1 7.1 7.1 7.1 3.6 3.6 3.6 GMP inspections are carried out by UK inspectors of manufacturing sites in third countries which are nominated as manufacturers or potential manufacturers of products that have UK marketing authorisations and in some cases those that have marketing authorisations issued by the European Medicines Agency (EMEA). Potential for microbial contamination has been a major concern at these sites for the past three years, with validation documentation and batch release procedures featuring for the first time in the top 10. As with UK industrial manufacturers, potential for non-microbial contamination appears to be decreasing in incidence. Table 1 (p593) records the number of serious deficiencies per inspection over the past six years. A higher incidence of serious deficiencies continues to be recorded at inspections in third countries than in the UK. The reasons for this are two-fold. First, inspections in third countries are product-related and thus more intensively focused than general GMP inspections in the UK and, second, some third country manufacturers, particularly sites nominated on UK/EMEA marketing authorisations for the first time, may not be familiar with EU GMPs and thus the standards which EU inspectors expect of them. The data for UK manufacturers include the results of inspections of the manufacture of investigational medicinal products (IMP) www.pjonline.com 04–05 Table 8: Comparison of GMP deficiencies for vaccine manufacturers and all sterile product manufacturers 2004–05 Category of GMP deficiency Manufacturing documentation Handling and control of packaging components Quality management Evidence of compliance with TSE guidelines Line clearance, segregation and potential for mix-up Validation documentation Failure to respond to previous inspection findings Batch release Cleaning validation Potential for non-microbial contamination 03–04 Potential for microbial contamination Design and maintenance of premises Quality management Quality system documentation Design and maintenance of equipment Environmental monitoring Starting material and packaging component testing Validation documentation Process validation Evidence of compliance with TSE guidelines 21 15 12 9 5 3 4 4 9 8 2 5 8 5 3 2 2 3 2 3 which is now a statutory requirement.Table 7 shows the top 10 serious GMP deficiencies from these manufacturers, in descending order and, together with Table 8, demonstrates how the deficiency database can be used to look at specific manufacturing activities. In view of the importance of documentation and packaging for IMPs, it is not surprising that these categories are prominent in the list. In other respects the list includes similar categories to that for other manufacturers. During 2004–05 much attention was focused on vaccine manufacture and the supply situation of influenza vaccine in the UK and the US.That interest continues today with regard to vaccines to provide immunity against a potential influenza pandemic. It is interesting to compare the findings from inspections of vaccine manufacturers with those from all sterile product manufacturers. Table 8 does this. The figures (rounded up or down) show a significantly higher incidence of deficiencies in regard to vaccine manufacture in the categories of potential for microbial contamination and design and maintenance of premises. Furthermore, higher incidences are demonstrated in eight of the top 10 categories of deficiency for vaccine manufacturers. The differences may be attributable to the particular and unique processes involved in vaccine manufacture and the facilities involved. Wholesale distributors It is important for distributors of medicinal products to bear in mind that their actions or omissions can have a significant effect on the quality of the products that they handle. Storage and transportation temperatures have more influence than any other factor on maintaining the quality of products throughout the distribution network and it is of major concern that inspectors continue to report deficiencies in these areas.The MHRA’s concerns in this regard are not restricted to those products that are commonly referred to as “cold chain products”. It is also concerned that “temperate chain products”, ie, those whose recommended storage temperatures range up to 30C, are also protected from extremes of temperature during storage and transportation.The agency has contributed to a number of open seminars and conferences on this subject and in July 2001 it published detailed recommendations on the control and monitoring of storage and transportation temperatures of medicinal products.4 There is an increasing trend in the reporting of deficiencies related to returns, and deficiencies concerning written procedures continue to feature. Reports of unauthorised activities by wholesale distributors have resulted in this category entering the top 10 for the first time. Examples include unlicensed assembly, use of unlicensed premises for storage and unauthorised importation of unlicensed medicines. Trading other than in accordance with an appropriate licence may result in adverse licensing action or enforcement action against the organisation concerned, or both. Sanctions The large majority of deficiencies reported to the manufacturer or wholesaler are remedied within an acceptable period without further action by the regulatory authority. However, where critical deficiencies are reported, or where a number of major deficiencies have resulted in a critical systems failure, more formal action may be required in order to protect public health. The MHRA’s Inspection Action Group (IAG) considers referrals from GMP and GDP inspectors resulting from adverse inspection findings that indicate an unacceptable patient risk. The group also considers referrals from inspectors and enforcement officers concerning breaches of medicines legislation. If the IAG considers that licensing action, or action concerning a Qualified Person or a Responsible Person is indicated, a recommendation will be made to the UK licensing authority for action to be taken.This can include suspension or revocation of a manufacturing authorisation or wholesale dealer’s licence, compulsory variation of the authorisation or licence to exclude certain activities or categories of product, compulsory variation of a marketing authorisation to remove a particular site of manufacture, or censure of a QP or RP. Thirteen GMP and GDP inspections for which critical deficiencies were recorded 20 May 2006 The Pharmaceutical Journal (Vol 276) 595 Articles Drug alerts A drug alert is classified into one of four categories, depending on its criticality and the speed with which action should be taken by the recipient. A Class 1 alert is issued when a defect is potentially life-threatening or presents a serious risk to health. The response to a Class 1 drug alert should be immediate, on receipt. A Class 2 alert (action within 48 hours) is issued when a defect could cause illness or mistreatment, but which is not Class 1. A Class 3 alert (action within five days) is one that, although not posing a significant hazard, nevertheless requires action. Where a defect poses no threat to patients, or is unlikely to impair product use or efficacy, the DMRC may issue a Class 4 “caution in use” alert. In addition to national distribution, Class 1 and Class 2 alerts are also sent by way of an established rapid alert system to EU/EEA member states, countries that have a mutual recognition agreement with EU, members of the Pharmaceutical Inspection Co-operation Scheme and agencies such as the EMEA and the US Food and Drug Administration. Defective medicines Listening Friends The MHRA’s Defective Medicines Report Centre (DMRC) plays a major part in the protection of public health by minimising the hazard to patients arising from the distribution of defective medicinal products. It does this by providing an emergency assessment and communications system between suppliers of medicinal products, the regulatory authorities and the users. It achieves this by: (i) receiving and assessing reports of suspected defective medicines, (ii) monitoring and, as necessary, advising and directing appropriate actions by the responsible licence/authorisation holder, and (iii) communicating the details of this action as necessary and with appropriate urgency to recipients of the products and other interested parties in the UK and elsewhere by means of drug alerts. A defective medicine may be defined as one that is likely to be harmful under normal conditions of use, one that is not in compliance with its marketing authorisation, one that is lacking in therapeutic efficacy or one that has been manufactured other than in accordance with GMP. Recalls are normally carried out by the marketing authorisation holder with help and advice from the DMRC who may issue a drug alert to recipients within and outside the NHS to support the recall. Not every substantiated defect results in a drug alert. Some organisations are able to identify every customer that received the defective product (for example, some hospital-only products) and where the MHRA has assurance that all customers can be reached, the DMRC may decide not to issue a drug alert to support the recall. However, the MHRA must be advised of any defect that could result in a recall and organisations 596 must not undertake a recall without first discussing it with the DMRC. The DMRC receives reports of suspected defective medicines from a variety of sources, including manufacturers, distributors, hospitals, pharmacies, GPs and the general public. During 2005 the DMRC received 271 reports of suspected defective medicines of which 41 were substantiated.These resulted in the issue of 25 drug alerts, including two at Class 1. Defects related to labels and leaflets (nine alerts), contamination, stability and packaging (four alerts each), and sterility assurance, efficacy, product mix-up and counterfeit products (one alert each). The Class 1 drug alerts were associated with a lack of sterility assurance and product mix-up.The recall of a counterfeit product in 2005 followed two recalls of counterfeit products in 2004. The Listening Friends Scheme offers free telephone help to pharmacists under stress. A call to the scheme will put the pharmacist in touch with a fellow pharmacist who will be there to give time to talk about the problems that are causing stress. The Listening Friend will have insight into the particular pressures that apply in pharmacy but the service is also there to help with problems not related to work, such as illness, disability, bereavement and relationship issues. The service is run by a team of volunteer pharmacists, who are all mature and experienced professionals in their field of practice. They have all been trained in listening skills and may be able to direct pharmacists under stress to more specialist help if needed. The Pharmaceutical Journal (Vol 276) 20 May 2006 Contact with the Listening Friends is made initially by telephoning 020 7572 2442 where a voicemail answering service will take details of a first name, a telephone number and a convenient time to call. A Listening Friend will then call back, usually on the evening of the same day or within 24 hours. Arrangements will be made to make further calls if the pharmacist would like more telephone time with the Listening Friend. The scheme is supported by the Royal Pharmaceutical Society’s Benevolent Fund and is part of the fund’s aims in supporting pharmacists in need. For additional information about the scheme, or the fund and the services it offers, call 01327 264739 or 01323 890135 or e-mail benevolent.fund@rpsgb.org Summary The objective of regulatory medicines inspection is to contribute to the protection of public health through the assessment of compliance by manufacturers and distributors of medicines with standards of good manufacturing practice and good distribution practice. Although there have been some changes in the incidences of reported serious GMP and GDP deficiencies in recent years, the lists of those most frequently cited categories for each manufacturing sector and for wholesale distributors continue to include categories for which concerns have been recorded in past inspections. Failure to comply with GMP and GDP can have a profound effect on product quality and patient safety and where this occurs the MHRA will take appropriate action in support of its prime objective. Those organisations that have issued product or batch recalls will be aware not only of the risks that they may have exposed patients to but will also be aware of the costs involved in a recall. The data reported above indicate to manufacturers and distributors areas on which they may wish to continue to focus their training programmes, internal audit and quality improvement. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS We acknowledge that the data presented in this paper were generated by MHRA’s GMP and GDP Inspectors. References 1. Taylor J, Turner J, Munro G. Good manufacturing practice and good distribution practice: an analysis of regulatory inspection findings. Pharmaceutical Journal 1998;261:748–51. 2. Taylor J, Turner J, Munro G, Goulding N. Good manufacturing practice and good distribution practice: an analysis of regulatory inspection findings for 1998/99. Pharmaceutical Journal 2000;265:686–9. 3. Taylor J, Munro G, Lee G, McKendrick A. Good manufacturing practice and good distribution practice: an analysis of regulatory inspection findings for 2001–02. Pharmaceutical Journal 2003;270:127–9. 4. Taylor J. Recommendations on the control and monitoring of storage and transportation temperatures of medicinal products. Pharmaceutical Journal 2001;267:128–31. Ownership changes were referred to the IAG in 2004–05. Ten of these resulted in recommendations to the UK licensing authority for action. As a consequence, five notices of intention to suspend an authorisation or licence were issued resulting in four suspensions pending the implementation of appropriate corrective action and one revocation. Five letters of censure were issued to QPs or RPs. When buying a pharmacy business the purchaser must contact the Royal Pharmaceutical Society prior to taking over the business to obtain the necessary “Application for transfer of ownership” form. Until this form is completed and returned to the Society, the Register will continue to show the premises as registered by the previous owner. A legal problem could arise from the new owner not advising the Society of a change of ownership. Section 76(3) of the Medicines Act 1968 provides that the existing registration automatically becomes void at the end of 28 days from the date on which a change of ownership occurs. www.pjonline.com