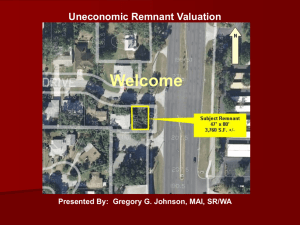

Against Remnant VP

advertisement