Generated on 2012-05-08 03:05 GMT / http://hdl.handle.net/2027

advertisement

Generated on 2012-05-08 03:05 GMT / http://hdl.handle.net/2027/umn.31951001501076w

Public Domain, Google-digitized / http://www.hathitrust.org/access_use#pd-google

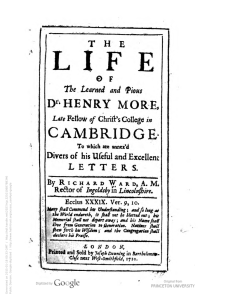

THE

Religious Ceremonies

OF THE

CHINESE

IN THE

Eastern Cities of the United States.

BY

STEWART CULIN.

AN ESSAY, READ BEFORE THE NUMISMATIC AND ANTIQUARIAN SOCIETY

PHILADELPHIA, AT ITS HALL, APRIL ist, 1886.

PRIVATELY FRIN'lED.

PHILADELPHIA,

Generated on 2012-05-08 03:40 GMT / http://hdl.handle.net/2027/umn.31951001501076w

Public Domain, Google-digitized / http://www.hathitrust.org/access_use#pd-google

1887.

Generated on 2012-05-08 03:41 GMT / http://hdl.handle.net/2027/umn.31951001501076w

Public Domain, Google-digitized / http://www.hathitrust.org/access_use#pd-google

ONE HUNDRED COPIES.

Franklin Printing House.

/

Religious Ceremonies of the Chinese

In the Eastern Cities of the United States.

THE Chinese who emigrate to America come from several districts

in the Province of Kwantung, adjacent to the city of Canton.

Niinhai and Pw'anyu, districts within which the provincial

capital is located, with Shunteh, called together the Sam Yup* or "three

towns," and Sinhwui, Sinning, Kaiping, and Nganping, the Sz' Yup,

or "four towns," with Hohshan, furnish almost the entire number.

They are principally country people, with a small sprinkling of

artisans and shopkeepers from the cities, a few of whom are from Canton

itself.

The people of the different districts vary somewhat in speech and

manners; those of the Sam Yup approximate in both language and cus-

toms to the inhabitants of the city of Canton, while the Sz' Yup people,

who largely outnumber the others, exhibit many local peculiarities, and

often speak a patois almost unintelligible to those who come from nearer

the capital. The immigrants bring with them the traditions and customs

of their country, and usually endeavor to maintain and re-establish

them here; but in their anxiety to accumulate money, and under their

changed conditions of life, they forget and neglect much they formerly

thought essential to their fortune and happiness. They live so much

* The Chinese words printed in italics are spelled according to Dr. Williams's Tonic Dictionary

of the Canton Dialect. Canton, 18o(i.

3

Generated on 2012-05-08 03:44 GMT / http://hdl.handle.net/2027/umn.31951001501076w

Public Domain, Google-digitized / http://www.hathitrust.org/access_use#pd-google

1142154

4

apart from other people, however, forming colonies in the large cities,

in which there are often many who cannot speak English, that much of

their primitive life is retained. It is in these centres that one finds

the strongest adherence to old customs, continually strengthened by

new arrivals, and fostered by native shopkeepers and others who profit

by them.

The religious ceremonies of the Chinese in the Eastern cities of the

United States, consist principally in burning incense and offering sacri-

fices to certain deities, in their laundries and shops, and in visiting at

the season of the New Year some convenient shrine to learn their

fortune for the following year by throwing the divining-sticks.

The first immigrants, uncertain whether the gods would still hear

their prayers and protect them in this remote land, neglected even

these observances; but as fortune favored them, many in time erected

a figure of their accustomed god and paid it the usual honors, attrib-

uting to its influence some part of their success. This deity was usually

the one most worshipped in the district from which the immigrant

came. In the course of time, as the people made homes for themselves,

some of their former many household gods were recognized.

At present one finds in most laundries and shops of our large

cities, a paper scroll with the picture of Kwan Ti or Kwanyiu,

and sometimes inscriptions on red or orange paper to the lares

and penates.

Kwan Ti, or Kwan Kung, "the Master Kwan," as he is popularly

called here, the Chinese God of War, is a deity almost universally

worshipped in China at the present day.* He was a general of the

Han dynasty, dying A. d. 219; and the events of his life, as

recorded in the historical romance of the Sam Kwok Chun, or "The

Records of the Three States," are verv familiar to the Chinese

here. None of their popular heroes has a greater hold upon their

affections, and the chapters of the story in which his life is related,

are read and re-read, often with tearful eyes. Legends are current

Generated on 2012-05-08 03:44 GMT / http://hdl.handle.net/2027/umn.31951001501076w

Public Domain, Google-digitized / http://www.hathitrust.org/access_use#pd-google

M. C. Inibault Huart, Revue de CHistoire den Relufions, tome xiii, p. 129.

5

of his having appeared at various times in the New World to

protect his worshippers. Once in Havana—so the tale runs—when a

fire broke out which threatened the dwellings of the Chinese colony,

a man of gigantic stature was seen to emerge from the flames and

they were at once extinguished, but not before all had recognized

in his majestic features and curious dress, the divinity to whom

they had built a temple.

Kwanyin, the "Goddess of Mercy," called here Kun Yam

p'o sat, is a deity of the Chinese Buddhists. They believe her to

be "the invisible head of the Buddhistic Church, the spiritual

Mentor of all believers," who "' hears with compassion the prayers

of those who are in distress,' and that in the execution of this

office, Kwanyin appears on earth in various forms (male and

female), to convey spiritual blessings to both sexes." *

Kwanyin is usually represented upon the scrolls, as a woman seated

upon a lotus flower with her two attendants, the boy, Hung-tseuk

Ming Wong, and the girl, Shin Ts'oi Lung Nit, ranged on either

side in attitudes of devotion. Many stories of her intervention in

China are told here, but I have not heard of any miraculous

appearances of this goddess in the Western Hemisphere.

The scrolls with the image of the god are suspended on the

wall; below there is usually a ledge, supporting a receptacle for in-

cense, with a pair of vases which serve as candlesticks on either side.

Incense (heung) is burned in the censer by some daily, and often

one or three cups of tea are kept filled, ranged along the ledge.

In China, special sacrifices are considered necessary on the

first and fifteenth days of .each Chinese month, the times of the

new and full moon. Here few observe the custom; but some, on

these occasions, set a table as if for three persons, with chop-sticks

and wine-cups duly arranged, and burning incense, place before the

invisible guests a cooked fowl and maybe a piece of roasted pork.f

* Rev. E. J. Eitel, Hand-Book for the Student of Chinese Buddhism. London, 1870, p. 19.

Generated on 2012-05-08 03:45 GMT / http://hdl.handle.net/2027/umn.31951001501076w

Public Domain, Google-digitized / http://www.hathitrust.org/access_use#pd-google

t Beef is generally avoided as food and is never served as a sacrificial offering.

Wine* is poured into the cups and certain invocations made to the

gods, before whom entire fowls and large portions of meat are always

served. Afterward the fowl and roasted pork are removed, chopped in

small pieces in the usual manner of serving such food, and again

placed upon the table as an offering to the spirits of the dead.

In China, the worshippers visit the temples and sacrifice to

the gods on the first and fifteenth days of the month, and

make offerings at home to the spirits of the dead on the second

and sixteenth days, but here sacrifices to both are usually made

upon the same day. Similar ceremonies are performed at the opening

of shops and restaurants.

Sunday, called by the Chinese in America lai pai (meaning

"rites, to worship"), is observed as a holiday, but no religious signifi-

cance is attached to it The days of our week are designated as

lai pai yat (one) Monday, lai pai i (two) Tuesday, and so on; the

Chinese calendar is followed, and some of its many festivals and

holidays celebrated, usually upon the Sunday succeeding the day upon

which they fall.

An almanac, called the Cung shit, is annually imported from

China and sold in the shops. This work is said to be issued by

Chang T'een She, the head of the Taoist fraternity in the Dragon

Tiger Mountain, and is not to be confounded with the imperial

almanac, which is never seen here. It contains a calendar in

which the celebrations for each day are indicated, with the appro-

priate horary characters used in divination; besides this, lucky

and unlucky days are designated, with rules for palmistry and

the interpretation of dreams, and much general information of a

useful character.

On the 5th of the Fifth month, dumplings, called tsung tsz,

are alwrays served in the restaurants in commemoration of the death

of K'ii Yiian.f They are made of a glutinous rice, no mai, im-

*A kind of spirits imported from China, called no mai Isau, and made from a glutinous

rice.

Generated on 2012-05-08 03:53 GMT / http://hdl.handle.net/2027/umn.31951001501076w

Public Domain, Google-digitized / http://www.hathitrust.org/access_use#pd-google

t W. F. Mayers. The Chinese Reader's Manual, Shanghai, 1874, p. 107.

7

ported from China for the purpose, and are wrapped in leaves

and steamed with a small piece of sapan wood which stains them

a bright red color.

The preparation and sale of cakes form a prominent feature

in the celebration of another principal holiday, the Autumn Moon

Festival, which occurs on the full moon of the Eighth month.

For some time before this occasion packages of cakes called

chung ts'au iit ping, or "mid-autumn moon cakes," are displayed

in the shops, and are bought and eaten by almost every one.

These cakes are baked in an oven, and are made of rice flour,

with a rich mass of chopped nuts and fruits in the centre.

They are circular in form, and have an appropriate device, such

as the rabbit pounding rice in a mortar, stamped on the top.

Here as in China, eating and drinking play an important

part in all their festivals, and a grand dinner usually constitutes

the only special observance on many of their national and relig-

ious holidays. Kwan Tf is honored on his birthday, the 13th of

the Fifth month, by additional candles and incense being burned

before his shrine, and it is often made the occasion of a banquet

by the / Hing, a powerful secret society that does much to keep

alive native customs and traditions.

The New Year is the season for general rejoicing, and no

work is done for several days. It is ushered in by a supper on

the night of the old year in most laundries and shops, when

employes and friends assemble and something of a ceremonial

character is given to the feast. Many recollections of home

are revived. The only occasion upon which the writer ever

heard any expressions of sentimental attachment to absent friends

and country, was at one of these midnight suppers before the

advent of the New Year.

The first dav is devoted to formal calling between friends and

acquaintances; every one wears his best clothes, and all endeavor

to array themselves in some new article of dress, if it is only

Generated on 2012-05-08 03:55 GMT / http://hdl.handle.net/2027/umn.31951001501076w

Public Domain, Google-digitized / http://www.hathitrust.org/access_use#pd-google

a pair of new shoes, in honor of the day. The laundries and

8

shops are decorated for the occasion; scrolls with appropriate

inscriptions are suspended on the walls, and the tablets of red

or orange paper with felicitous mottoes, supposed to bring good

luck, are taken down and new ones substituted in their places.

Some put a long paper hanging, upon which are representations

of several personages, whom they call Fuk Luk Shau Sing Kung,

"The Starry Sages of Happiness, Honor (official advancement), and

Long Life," in a prominent place on the wall. Plates of oranges

and dried fruit are arranged on a table in front of this scroll,

with large candles and a censer in which incense is burned; sandal-

wood, fan heung, is often substituted in this for the incense sticks

commonly used.

Three principal figures usually appear in these pictures. Above

is Kwok Tsz' I,* a general of the T'ang dynasty, renowned for his

services to the state under four successive emperors, and for the

many blessings he enjoyed of honors, riches, and longevity; on

the right, Tau In Shan, whose five sons all attained the highest

literary rank; and in the foreground on the left, Tung Fung

Sok, a mythical beiug, who figures in the popular romance entitled

the Shui U Chi'm ("The Story of the River's Banks"), and is

reputed to have attained a fabulous longevity.

Very few of the Chinese here are familiar with the historical

names attributed to these personages, and the scroll and offerings

are regarded as part of the merrymaking of the season, and little

if any religious significance is attached to them.

The remaining days of the celebration are devoted to feasting

and conviviality, and the gambling tables, which are reopened after

the first day, are largely patronized.

Gambling constitutes the amusement or profession of a large

part of the people, and the gamblers have many superstitions. The

keepers of gambling-houses avoid all colors, save white, in the

walls and decorations of their rooms. White, the color of mourn-

Generated on 2012-05-08 03:57 GMT / http://hdl.handle.net/2027/umn.31951001501076w

Public Domain, Google-digitized / http://www.hathitrust.org/access_use#pd-google

* W. F. Mayers, The Chinese Header's Manual, p. 96.

9

ing, the color of the robes worn by the spirits of the dead,

always considered inauspicious, is associated with the idea of losing

money, and is thought to bring such fortune to their patrons, with

corresponding gains to themselves. Even the inscriptions to the

tutelary spirit, are always written upon white paper, and white can-

dles are burned before his shrine instead of the red ones ordi-

narily used. The gamblers pray and sacrifice to Kwan Ti for

good fortune, and there is often a shrine to this god near the

gambling-houses for their convenience. Before making a hazard

in the pdk kbp piu, a kind of lottery, the player frequently buys

a bundle consisting of two small candles, a package of incense, and

several sheets of a certain kind of mock money, tai kong pb,

which may be had at any of their shops, and burns them before

the picture of the divinity.

The public worship of the Chinese, as distinguished from their

household observances and the customs of the gamblers, consists, as

before stated, in annually visiting some shrine for the purpose of

divining their fortune for the year.

Their first public shrine in our eastern cities was erected about

ten years ago in the loft of a laundry at Belleville, New Jersey,

where a number of Chinese were employed. This has since be-

come the principal place of pilgrimage at the season of the New

Year. More recently, the shopkeepers in New York city sub-

scribed a sum of money and fitted up a room as a guild-hall

in the second story of No. 18 Mott Street, in which, as is cus-

tomary, a shrine was erected; Kwan Ti was the deity installed,

and a man was placed in attendance to instruct worshippers

and perform the necessary rites. In time, the New York colony

being very prosperous, it was thought that better provision

should be made for the god under whom they had flour-

ished, and another room was obtained in Chatham Square and

handsomely furnished, in the Chinese fashion. The scroll bearing

Generated on 2012-05-08 04:06 GMT / http://hdl.handle.net/2027/umn.31951001501076w

Public Domain, Google-digitized / http://www.hathitrust.org/access_use#pd-google

the picture of Kwan Ti was carried at midnight, in solemn pro-

10

cession, and placed in the new shrine. This ceremony took place

in the fall of the year 1885.

This guild is called the Chung Wd JCung Sho, or "Chinese

Public Hall," and is supported chiefly by contributions from the

Chinese merchants in New York. Its subscription books are cir-

culated among the Chinese in the neighboring cities.

There are no regular priests of the recognized religions of China

at either of the temples mentioned. No direct charge is made to

worshippers, but the candles, incense, and mock money required are

sold—at an advance upon their cost—in Chatham Square for

twenty-five cents, and at Belleville for fifty cents. These materials

are all imported from China.

The Chinese in Philadelphia were without any public temple

until about three years ago, when the owner of a laundry

in the lower part of the city, won five hundred dollars in

the pdk kbp piu, and devoted part of the money to the erection

of a shrine in his laundry. He was influenced by a desire to

propitiate the deity to whom he attributed his good fortune, but

he died shortly after completing the work. The laundry passed

into the hands of his brother, who, although he attends a Christian

Sunday-school, and has placed various Christian texts on the

walls of his shop, maintains the shrine and carefully observes the

religious customs of his country.

Early in their year, usually during the first week, having

selected a fortunate day for such inquiries by consulting the t'ung

shit, such of the Chinese in Philadelphia as are unable to visit

the more distant temples that have an established reputation, resort

to this place to learn the will of heaven as to their future, by

throwing the divining sticks before the picture of the god. The

questions asked are about their health, success in business, and such

other important matters as may concern them during the remainder of

the year. The answers, which are accompanied by cautions as to the

good or bad fortune likely to attend certain actions, often materially

Generated on 2012-05-08 04:03 GMT / http://hdl.handle.net/2027/umn.31951001501076w

Public Domain, Google-digitized / http://www.hathitrust.org/access_use#pd-google

influence their conduct for that period. The god is not ap-

11

pealed to again unless some special inquiry is made, it being

considered inauspicious to call upon him a second time, particu-

larly after having received a favorable answer.

I visited this shrine, upon the invitation of the proprietor, on

Sunday, the 7th of February, of this year (1886), the fifth day

of the Chinese year, and a day marked in the t'ung shii as very

favorable for certain kinds of divination. The owner intended to

consult the omniscient Kwan Ti, to learn the fortune in store for

himself and his partners for the year.

The place had a holiday appearance: a table was spread with

nuts and candied fruits for New Year's callers, a number of whose

red paper cards lay piled upon it.

Against the wall in the front room was the shrine, a picture

of which is presented in the frontispiece. It consists of a substan-

tial framework of carved and painted wood, extending from about

three feet from the floor nearly to the ceiling. A table in front

of this forms the altar.

Upon the centre panel, in gilded letters carved in relief, appears

the legend, Lit shing Kung, or the "temple for several sages;"

upon the right-hand panel, Tsik shan yan x hoi li lo, "Relying

upon Divine favor to open an advantageous pathway;" on the

left, P'ang shing talc i kwong ts'oi itn, "Abiding by sacred virtue

in order to enlarge the source of wealth."

Within the frame, suspended on the wall, hang paper scrolls

bearing pictures of the divinities.

Chang T'een She (called here Cheung T'in Sz) appears on the

scroll on the left. "Chang T'een She—that is, Chang, the Secre-

tary or Preceptor of heaven—is the posthumous title conferred upon

Chang Tao Ling, celebrated as one of the Sien, or immortalized

beings of the Taoist mythology, and the patron of this sect. Born

« a. d. 34, he early became versed in the writings of Lao Tsze,

and the most recondite treatises relating to the philosophy of

divination. He obtained the elixir of life through instructions con-

Generated on 2012-05-08 04:07 GMT / http://hdl.handle.net/2027/umn.31951001501076w

Public Domain, Google-digitized / http://www.hathitrust.org/access_use#pd-google

veyed in a mystic treatise, supernaturally received at the hands of

12

Lao Tsze himself, and at the age of one hundred and twenty-three

years, after a life 2)aase<^ in study and meditation, compounded

and swallowed the grand elixir, and ascended into heaven to enjoy

the bliss of immortality. Before leaving earth he bequeathed his

secret to his son, Chang Heng, and the tradition of his attainments

lingered about the mountain called Lung Hu Shan (' Dragon Tiger

Mountain'), where he had passed the later years of his earthly life,

until a. d. 423, when one of his sectaries, K'ou Kien-Che, was pro-

claimed his successor in the headship of the Taoists, and invested

with the title of T'een She, which was reputed to have been con-

ferred upon Chang Tao Ling. Successive emperors confirmed the

privileges of the sage's descendants, and in a. d. 1016, Sung Chen

Tsung enfeoffed the existing representative with large tracts of land

near Lung Hu Shan."* Here the successor of Chang T'een She,

under the same title, still maintains a petty court, and is believed

to rule the world of spirits. His name and powers are re-

garded with much respect by the Chinese in America.

He is represented on the scroll as a man of grave and dig-

nified mien, seated upon a tiger. He wears a green robe, and

holds a fly-brush, mo so, an emblem of divinity, in his left hand,

in the right an open book. His head is shaven, except for a

tuft of hair on the crown, covered with a small headdress. On

either side above the figure are clouds, upon one of which rests

a vase containing a green plant, with a sword plunged downward

through the cloud beside it. On the other cloud is an ornamental

green tablet with the inscription,"'^ lid ho ling," "Controlling

the roar of the Five Thunders."

The next scroll, which is soiled and time-worn, bears the

effigy of Un T'dn, a deity reputed to be a god of wealth, and

much worshipped in the Sinning district, from which the brothers

came. This scroll hung in the laundry before the erection of the

Generated on 2012-05-08 04:10 GMT / http://hdl.handle.net/2027/umn.31951001501076w

Public Domain, Google-digitized / http://www.hathitrust.org/access_use#pd-google

* W. F. Mayers, Opus cil., p. 11.

13

shrine, and was painted in Chicago, and brought to Philadelphia

by one of the former owners of the place.

tin T'(hi is depicted as a man in military dress, with a

serrated sword in one hand and a piece of gold in the other.

At his feet crouches the tiger (" wealth ?") which, according to

tradition, he commands.

Kwan Ti is figured on the next scroll. He appears as a

man of commanding appearance, with a long black beard, wearing

a green robe, and seated on a kind of throne. His right hand

is raised, as if in exhortation, while his left hand is concealed in

the folds of his dress. He is supported on one side by his faith-

ful servitor, Chau Ts'ong, with an enormous halberd, and on the

other by his adopted son, Kwan P'ing, holding his official seal

wrapped in a yellow silk bag.

Beside the last scroll, on the extreme right, hangs a board,

painted red, with an inscription in honor of Kwanyin, that serves

instead of a scroll, with her image.

On the ledge, within the frame, is a large box full of sand

to hold incense, and a small gilt shrine containing an idol. This

was the gift of some American friend of the proprietor, and its

identity is not surely known to him, but he regards it as an

image of Buddha and considers it a desirable acquisition. At

either extremity of the ledge, without the frame, are silvered

glass vases, holding bunches of artificial flowers, while similar

vases between are used as candlesticks, with another in the

centre for incense. The implements used in divinations are seen

on the table; two elliptical pieces of hard wood, rounded on

one side and flat on the other, kdu pui, and a tin box contain-

ing one hundred bamboo splints about seven inches in length,

called ts'un u.

It was growing dark when I entered the laundry, and the

owner had let down his queue, put on his best robe, and was

waiting with covered head to receive the cooked meats from the

Generated on 2012-05-08 04:16 GMT / http://hdl.handle.net/2027/umn.31951001501076w

Public Domain, Google-digitized / http://www.hathitrust.org/access_use#pd-google

kitchen for the sacrifice. He lighted two large painted candles in

14

the candlesticks, and after waving a bundle of incense three times

before the shrine, ignited it in the flame of a candle, and care-

fully disposed the smoldering sticks before the different represen-

tations of the divinities.* Three were first stuck in the large sand

box before Kwan Tf, and then three before each of the other scrolls.

Three were placed in the shrine of the Lord of the Land, a small

box on the right of the altar, by the wall, one was carried back

into the kitchen and put beside the stove for the Tsb Shan, the

"God of the Furnace," and one was stuck in the woodwork by

the door opening into the street. This was done to let the spirits

know that a ceremony was being performed in their honor.

The altar was arranged as if for a banquet; three wine-cups,

tsau pui, and three pair of chop-sticks, fdi tsz1, were placed in

front of the scrolls and a boiled fowl, trussed in a peculiar fashion,

with a large piece of roasted pork were handed the priest and

similarly deposited.

The priest filled the cups with wine from a jar, and lifting

one of them on high, passed it three times through the smoke of

the incense, and poured part of the wine upon the floor. Then

he bowed three times, and knelt and prayed silently. His prayer

was something like this: "O Kwan Ti! will you please come

and eat, and drink, and accept this respectable banquet. I wish

to know about the future, and what will happen to me this year.

If I am to be fortunate, let me have three shing pui"

He rose, took the kdu pui, and passed them three times

through the rising smoke. Then, kneeling again, he held the Mu

pui, with the flat sides placed together, above his head, and let

them drop to the floor. When they fell, both lay with their curved

sides uppermost, yam\ pui. This indication is considered a nega-

tive one, neither for good nor evil. Again they were let fall.

* Care is taken to extinguish the flame of the incense with a motion of the hand

rather than with the breath, which would de61e it. One or three sticks, or an entire

bundle, sire always burned, never four, five, seven, etc.

Generated on 2012-05-08 04:18 GMT / http://hdl.handle.net/2027/umn.31951001501076w

Public Domain, Google-digitized / http://www.hathitrust.org/access_use#pd-google

t Yam (Yim), the lesser of the two dual powers, the female or recipient in nature.

15

This time both flat sides lay uppermost, yeung* pui, unfavorable.

The third time one lay with the flat and the other with the

rounded side above, shing pui, a favorable sign. The kdu pui are

thrown until three yam, yfang or shing pui are obtained in suc-

cession. This indicates the answer of the god, and is either an

indifferent, evil, or good omen, as the case may be.

Three shing pui were the fortune of the priest, but he would

know more of the future. He knelt and prayed again,—" O

Kwan Ti! I beg you will let me throw the ts'un u. If you

will, grant ine three shing pfii." Again the kdu pui were thrown,

and three shing pui indicated the answer of the god.

The ts'un it are numbered from one to one hundred, corre-

sponding with the numbers of the pages of a book entitled Kwan

Tai ling ts'im, the "Kwan Ti Divining Lots." Each page of this

book contains a verse of poetry referring to some well-known per-

sonage in Chinese history, and his life and conduct are supposed

to furnish a clew to the future of the individual whose fortune is

under consideration. A short explanation accompanies each passage,

but a very extended knowledge of the Chinese annals is consid-

ered necessary for the satisfactory interpretation of the oracle.

The priest knelt and prayed, and asked whether he would

make much money during the year. Then he rose, took the

box containing the ts'un ii, and after waving it thrice through the

smoke, knelt and shook it violently, until one of the sticks fell

upon the floor. He wrote the number of the splint on a piece

of red paper, and threw the ts'un u until all of his questions

were answered.

This accomplished, he took several narrow slips of paper, Mai

ts'in, pierced with holes, and said to represent as many cash

(ts'in) as there are holes, and wrapped them in some larger sheets

of paper, tai kong po,f upon which tin foil had been pasted, and,

* Yeung (Yang), the greater of the dual powers, the masculine.

t The sheets of tai kong pv are cup-shaped, and usually have the character thau, "long

life," cut in red paper and pasted on the silvered surface. Two sheets of the large kind, or

Generated on 2012-05-08 04:25 GMT / http://hdl.handle.net/2027/umn.31951001501076w

Public Domain, Google-digitized / http://www.hathitrust.org/access_use#pd-google

hvp pairs of a smaller kind, are generally used.

1G

after waving the bundle three times before the altar, ignited it

and put the blazing mass in an iron pot, pb lb, where it was con-

sumed. During the entire ceremony—which lasted about half an

hour, and was conducted in the most reverential manner—he did

not speak a word.

After it was over, the attendants carried the roast meat back

into the kitchen, where it was cut in small pieces in the Chinese

manner of serving for the table, and again brought in, with other

dishes containing food, and all were placed on a low platform

before the shrine of the "Lord of the Land," the tutelary spirit.

The offerings were allowed to remain there for a short time, when

the wine was poured back into the jars from the cups before Kwan

Tf, and served with the carved meats for dinner to the assembled

company.

The shrine for the "Lord of the Land" may be seen in the

illustration, on the right of the table. It consists of a shallow

wooden pent house, shan lau, "assembly place for spirits," within

which is an inscription. The box is painted red and ornamented

with bunches of the tinsel flowers, kam fd; a lamp is usually

kept burning before it and cups for tea are placed within or on

the floor outside. Such shrines are erected in laundries and shops

after the owners have successfully carried on business for several

years. The inscription on the one represented is herewith repro-

duced. The three central columns are written on a tablet of

orange-colored paper within, while the outer ones are placed on

the panels of the shrine.

Above in the centre may be read Shang kam, "Producing

wealth." Below this, in the same column, T'ong Fan Ti Chit tsip

yan Ts'oi Shan, "Chinese and Foreign Lord of the Land receive

and introduce the God of Wealth!" The lines on either side are

complimentary titles bestowed upon the spirit ruler; Chin ts'oi t'ung

tsz\ "Invite Wealth Boy," and Tsun pb sin long, "Increasing

Treasure Sage."

Generated on 2012-05-08 04:26 GMT / http://hdl.handle.net/2027/umn.31951001501076w

Public Domain, Google-digitized / http://www.hathitrust.org/access_use#pd-google

The outside couplets on the panels of the box read as follows:

Generated on 2012-05-08 04:35 GMT / http://hdl.handle.net/2027/umn.31951001501076w

Public Domain, Google-digitized / http://www.hathitrust.org/access_use#pd-google

Generated on 2012-05-08 04:33 GMT / http://hdl.handle.net/2027/umn.31951001501076w

Public Domain, Google-digitized / http://www.hathitrust.org/access_use#pd-google

19

Sik nin wai Ti Chi)

Kam yat sh'i Ts'oi Shan.

"In former years (he) became a Lord of the Land,

"To-day (he) is a god (or spirit) of wealth."

The ghost of the first person who dies in a house is believed to

become its Ti Qui, "Lord of the Land," or, rather, "Lord of the

Place," and as such is thought to preside over and govern its other

ghostly inmates. Every house is thought to have its ghosts, either

the spirits of those who have died within it or strange ghosts who

have selected it for their dwelling; the shan lau is built for their

shelter, and when suitable offerings are made to them they are seldom

thought to disturb the living. The ghosts are always kindly spoken

of and their aid invoked, as may be seen from the inscription, to

bring wealth and prosperity.

Foreign as well as Chinese spirits are honored, but this is

done more as a matter of form than from any assurance that

they will understand or appreciate the attentions paid to them.

"Poor ghosts," I have heard said of them, "they cannot read our

writing; they do not care for the tea and rice, or even know why

we build the shrine. Alas! we have done all we could, but it is

of no use to them."

These foreign ghosts are much feared by many of the more

ignorant country people, and strange tales are told concerning them.

One man opened a laundry in a village near Philadelphia and

thought to establish a successful business, but every night after he

had extinguished the lights a human face appeared, floating in

the air. He left the place precipitately and abandoned the enter-

prise. The ghosts are thought to make their presence known

at night, when they disturb sleeping persons by pulling at their

bed-clothes and sometimes appearing in the form in which they

once lived. The spirits of their own countrymen are believed to

occasionally give trouble, and a house in which a Chinaman dies

is often reputed to be haunted.

Generated on 2012-05-08 04:36 GMT / http://hdl.handle.net/2027/umn.31951001501076w

Public Domain, Google-digitized / http://www.hathitrust.org/access_use#pd-google

The chief use of the pictures of the divinities enshrined in

20

private houses is to tranquillize and drive away refractory spirits.

Cheung T'in Sz, Kwdn Tai, On T'dn, and Chung Kiv'ai, the

latter a man of the T'ang dynasty, now deified as a protector

against devils,* are considered particularly efficacious for this purpose.

Charms, such as the pat kwd or eight diagrams, with various

inscriptions, are sometimes placed on the panels of the doorway

to prevent the entrance of wandering ghosts.

In China the rites paid to the spirits of the dead constitute

the most important part of religious ceremonials, but here, where

no tablets to ancestors are erected, but few of the many customs

are observed.

In the spring-time, during the Third Chinese month, it is

customary to visit the graveyards, where those who die are tempo-

rarily buried, carrying dishes of roasted pork and cooked fowls,

and, after burning incense and reciting certain prayers, place the

dishes upon the graves. There the sacrifices are allowed to remain

for a short time, but after the ceremonies are over, they are car-

ried home and eaten by the mourners. These rites are only per-

formed when there remain some friends or relatives of the deceased

who preserve the memory of their comrade.

About the middle of the Seventh Chinese month, which falls

during our autumn, paper clothes, i chi, are burned by many in their

laundries and shops. They consist of oblong packages of tissue

paper of several colors, said to represent rolls of cloth or silk,

or small pieces of the same paper rudely cut and pasted in the

form of garments. K'ai ts'in and a kind of mock money, called

tai pin pb, or "large flat money," are burned at the same time.

This rite appears to be performed for the benefit of the spirit

world at large, both Chinese and foreign ghosts being propitiated

or honored. The belief is entertained that the paper clothes and

money actually meet the requirements of the spirits, and the inade-

quate size of the clothes is explained by the statement that the

Generated on 2012-05-08 04:38 GMT / http://hdl.handle.net/2027/umn.31951001501076w

Public Domain, Google-digitized / http://www.hathitrust.org/access_use#pd-google

* S. Wells Williams, A Tonic Dictionary of the Chinese Language. Canton, 1856, p. 206.

21

ghosts are much more contracted in size than the bodies of those

they once animated. A similar reason is given for the position of

the shan lau, it being placed upon the floor in order that it

may be more accessible to the ghosts.

When wine is drank it is customary to first pour a portion

from the cup upon the floor as an offering to the spirits, the

libation being thrown backward toward the right.

The ceremonies connected with the burial of the dead are much

the same as those observed by the same class in China. Some of the

Sinning people lay a pack of Chinese playing-cards as a charm upon

the coffin. A large part of the savings of the deceased are fre-

quently devoted to paying the expenses of the funeral, and among

the / Hing this is often conducted with much formality, the mem-

bers of the society going in a procession to the grave.

The proprietor of the shrine in Philadelphia burns incense

daily, before a piece of red cotton cloth tacked on the wall in his

laundry, for the spirit of his dead brother, and on the eve of the

New Year he placed an offering of meat and rice before it, "to give

his brother in hell a good supper," as he explained to me. No

emblems of mourning are worn for friends or relatives who die in

America, but upon the news of the death of a parent in China,

many plait a blue cord in their queue, and some wear blue shoes

and other articles of dress of the same color for a certain period.

Dutiful sons often hasten home on these occasions to pay the

necessary rites.

In addition to the deities mentioned, shrines may occasionally

be seen erected in honor of Shing Mb, "the Holy Mother," the

goddess worshipped by sailors, indicating, it is said, the presence

of some of the tdnkd, or boat-people, among the immigrants.

These shrines usually contain a small, throne-shaped chair with

a red cushion, to serve as a seat for the divinity. Such objects

are brought from China, where they are said to be placed in the

bombs exploded by the gentry on festival occasions and eagerly

Generated on 2012-05-08 04:46 GMT / http://hdl.handle.net/2027/umn.31951001501076w

Public Domain, Google-digitized / http://www.hathitrust.org/access_use#pd-google

sought by the people when they fall, and put in their domestic

22

shrines to invite good fortune. No representations of Slung 31b

are worshipped, but a tablet is placed within her shrine with an

inscription in which she is invoked as the Guardian of the State,

the Protector of the People, and the Queen of Heaven.

Yuh-hwang Sluing Ti, the "Pearly Emperor Supreme Ruler,"

the chief god of the Taoist pantheon, is regarded by the Chinese

here as the supreme ruler of the universe who governs all the

other deities, but no rites are performed in his honor nor is he

the object of particular reverence. Pak Tai, the Northern Ruler,

is the deity generally spoken of as Sluing Ti, but he is only

placed on an equality with Kwdn Tai, tin T'an, ami the other

deified heroes.

Many of the lesser deities are thought to be directly subject

to Chang T'een She, who has uuder him a multitude of spirits

who govern the invisible world. Among them are the Tb

Shing Wong, who rule municipalities, and the T'b ti Kung, or

street gods. No shrines to the latter are erected in our Eastern

cities, but in San Francisco each street in the Chinese colony

has its protecting divinity, the location of whose shrine is indicated by

the spirit's own choice, as revealed by throwing the divining blocks.

Yuh-hwang Sluing Ti, called here Yuk Tai, or the "Pearly

Ruler," is believed to reside continually in heaven. Kwan Ti,

Kwanyin, the To Shing Wong, T'o ti Kung, and other deified spirits

are thought to alternate between heaven and earth, and are spoken

of as p'b sat (Sanskrit, Bodhisattva), although the more learned

apply this term only to Kwanyin. Pdi p'b sat is the expression

commonly used for "worshipping the gods."

I have not attempted to define the religious belief of these

people, nor is it possible for us to say that they are either Tao-

ists, Buddhists, or Confucians. While they practise ceremonials

peculiar to all these religions and worship their several deities,

there seems to underly these observances a kind of fetichism,

primitive and instinctive, which constitutes the essence of their belief.

Generated on 2012-05-08 04:48 GMT / http://hdl.handle.net/2027/umn.31951001501076w

Public Domain, Google-digitized / http://www.hathitrust.org/access_use#pd-google

Education has repressed it among the learned, but with the mass

Generated on 2012-05-08 04:55 GMT / http://hdl.handle.net/2027/umn.31951001501076w

Public Domain, Google-digitized / http://www.hathitrust.org/access_use#pd-google

Generated on 2012-05-08 06:30 GMT / http://hdl.handle.net/2027/umn.31951001501076w

Public Domain, Google-digitized / http://www.hathitrust.org/access_use#pd-google

Generated on 2012-05-08 05:03 GMT / http://hdl.handle.net/2027/umn.31951001501076w

Public Domain, Google-digitized / http://www.hathitrust.org/access_use#pd-google

Generated on 2012-05-08 05:04 GMT / http://hdl.handle.net/2027/umn.31951001501076w

Public Domain, Google-digitized / http://www.hathitrust.org/access_use#pd-google

Generated on 2012-05-08 04:56 GMT / http://hdl.handle.net/2027/umn.31951001501076w

Public Domain, Google-digitized / http://www.hathitrust.org/access_use#pd-google

Generated on 2012-05-08 04:56 GMT / http://hdl.handle.net/2027/umn.31951001501076w

Public Domain, Google-digitized / http://www.hathitrust.org/access_use#pd-google