Untitled

advertisement

© S.B.M. Hoffmann -- June 2011

Acknowledgements

It is a pleasure to thank those who made this thesis possible. I am particularly grateful to Professor

Pierre Larouche for his valuable comments and guidance throughout the whole writing process. I

would also like to make a special reference to my colleagues from the International and European

Public Law department, especially Raluca Deaconu, for their support and their useful suggestions.

This work has also been greatly facilitated thanks to the encouragements of my family.

Lastly, a very special thought goes to Karolin whom I could always find solace in.

i

ii

Abstract

In the (digital) economy of the 21st Century, customers benefit from better and easier access to

information regarding price, quality and originality of products on a given market. In order to meet

the needs of their customers, firms need to be very responsive and to adapt continually to an everevolving environment. Some companies seem to detect more effectively what will be the next

trends on a market and even act as trendsetters. Other firms simply try to follow these trends.

In order for the latter to be/remain efficient on a market, they need to get inspiration from other

companies' good practices. Providing this information is the aim of benchmarking, a management

technique used to measure the performance of one’s company against the best in the same or in

another industry in order to improve one’s processes.

Paramount to benchmarking is the access to relevant information stemming from a target company.

In that sense it will be subject to the scrutiny of competition authorities.

Confronting the most widely used benchmarking techniques with the European (hard and soft) law

on competition, this thesis aims at clarifying which information is not supposed to be shared among

competitors on a market and which techniques should not be deemed harmful to competition.

iii

iv

Table of contents

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ............................................................................................................................................... i

ABSTRACT .................................................................................................................................................................... iii

INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................................................1

CHAPTER I: HOW DOES EU COMPETITION LAW UNDERSTAND EXCHANGES OF INFORMATION? 11

SECTION 1: INTRODUCTION TO THE NEW GUIDELINES ON HORIZONTAL COOPERATION AGREEMENTS ......................... 11

SECTION 2: MARKET CHARACTERISTICS THAT FAVOUR A COLLUSIVE OUTCOME STEMMING FROM AN INFORMATION

EXCHANGE AGREEMENT (ASSESSMENT UNDER ARTICLE 101(1) TFEU).............................................................................. 14

§1: Transparency.................................................................................................................................................................................... 15

§2: Concentration................................................................................................................................................................................... 15

§3: Complexity ......................................................................................................................................................................................... 16

§4: Stability of demand and supply conditions ........................................................................................................................ 17

§5: Symmetry ........................................................................................................................................................................................... 17

§6: Long-lasting commercial relationships ............................................................................................................................... 18

SECTION 3: CHARACTERISTICS OF THE INFORMATION EXCHANGE THAT FAVOUR A COLLUSIVE OUTCOME (ASSESSMENT

UNDER ARTICLE 101(1) TFEU) ................................................................................................................................................... 18

§1: Strategic nature of the information....................................................................................................................................... 19

§2: Market coverage ............................................................................................................................................................................. 21

§3: Individualization of the information ..................................................................................................................................... 22

§4: Age of the information ................................................................................................................................................................. 25

§5: Frequency of the information exchange .............................................................................................................................. 26

§6: Publicity of the information exchange and of the data thereof ................................................................................ 27

SECTION 4: CLEARANCE OF AN INFORMATION EXCHANGE AGREEMENT FOUND UNLAWFUL UNDER ARTICLE 101(1)

TFEU (ASSESSMENT UNDER 101(3) TFEU) ............................................................................................................................. 28

§1: Efficiency gains ................................................................................................................................................................................ 28

§2: Indispensability ............................................................................................................................................................................... 30

§3: Pass-on to consumers & non-elimination of competition ............................................................................................ 30

§4: Examples and summarizing tables......................................................................................................................................... 30

CHAPTER II: BENCHMARKING AS A MANAGERIAL TOOL THAT IS LIKELY TO BE SEEN CRITICALLY

BY LAWYERS ............................................................................................................................................................... 33

SECTION 1: WHAT IS BENCHMARKING? ....................................................................................................................................... 33

§1: Different kinds of benchmarking............................................................................................................................................. 34

A) Internal benchmarking ......................................................................................................................................................... 34

B) External benchmarking......................................................................................................................................................... 35

§2: The typical steps of a benchmarking exercise ................................................................................................................... 36

A) Determine which activities to benchmark (and how this will be done)...................................................... 36

v

1. Which activities? ................................................................................................................................................................................36

2. What benchmarking team? ...........................................................................................................................................................37

3. How to conduct the study? ............................................................................................................................................................38

B) Determine key factors to measure ........................................................................................................................... 40

C) Identify foremost practice companies .................................................................................................................... 40

1. Financial Results................................................................................................................................................................................41

2. Strategies ..............................................................................................................................................................................................42

3. Overall Business System ................................................................................................................................................................42

D) Measure performance of foremost practice companies and compare it to your own

performance ............................................................................................................................................................................ 43

1. Analysis of publicly available data ............................................................................................................................................44

2. Collection of data from discussion with informed persons............................................................................................44

3. Direct exchange of information with competitors .............................................................................................................44

4. Data analysis .......................................................................................................................................................................................45

E) Develop plan to meet and exceed or improve lead ........................................................................................... 45

F) Obtain commitment from management and employees................................................................................. 45

G) Implement plan and monitor results ...................................................................................................................... 45

H) Start over the whole process ..................................................................................................................................... 47

SECTION 2: HOW DOES BENCHMARKING RELATE TO EU COMPETITION LAW? .................................................................... 47

SECTION 3: WHY DO ECONOMISTS AND LAWYERS DISAGREE? ................................................................................................ 50

§1: Managerial viewpoint .................................................................................................................................................................. 50

§2: Legal viewpoint ............................................................................................................................................................................... 51

CHAPTER III: BENCHMARKING AS A PRO-COMPETITIVE TOOL THAT INCREASES COMPANIES'

ECONOMIC PERFORMANCE.................................................................................................................................... 55

SECTION 1: WHAT FEATURES OF A BENCHMARKING EXERCISE ARE LIKELY TO POSE PROBLEMS WITH REGARDS TO EU

COMPETITION LAW?........................................................................................................................................................................ 55

§1: Benchmarking needs strategic information ...................................................................................................................... 55

§2: Benchmarking is likely to rely on non-aggregated information .............................................................................. 56

§3: Benchmarking is only relevant with recent data ............................................................................................................ 56

§4: Benchmarking is conducted on a frequent basis ............................................................................................................. 57

§5: Benchmarking is not public ....................................................................................................................................................... 57

SECTION 2: RECONCILING BENCHMARKING AND COMPETITION LAW .................................................................................... 58

§1: Advice for firms ............................................................................................................................................................................... 58

§2: Advice for the Competition Authority ................................................................................................................................... 62

CONCLUSION ............................................................................................................................................................... 65

BIBLIOGRAPHY .......................................................................................................................................................... 67

vi

'As freak legislation, the antitrust laws stand alone. Nobody knows what it is they forbid'.

Isabel Paterson (unsourced)

The famous Canadian-American journalist and philosopher Isabel Paterson once stated her disbelief

in the soundness of the antitrust laws as a means to regulate the economic activity. We have to

acknowledge that this opinion was expressed by a person little known for her sympathy towards

State regulation (she was indeed one of the Founding Mothers of the American Libertarianism).

However this critic does make some sense if one thinks about certain aspects of European

Competition Law, especially its position vis-à-vis information exchanges in general and

benchmarking in particular. Before considering these issues, let us first briefly turn to the concept of

Competition Law.

Since 1 December 2009, two Treaties are in force in the European Union: the Treaty on European

Union (TEU) and the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU). The latter deals in

great detail with competition issues, i.e. the regulation of the exercise of market power by economic

operators.

Indeed, in order to ensure the completion of an Internal Market (formerly Common Market) with

free movement of people, goods, services and capital, and to safeguard consumer welfare attention

has to be given to companies' (or in the EU jargon undertakings) but also governments' behaviour

on the market. From this requirement we draw four main policy areas where EU Competition Law

applies:

− Cartels or any other form of collusion or anti-competitive practice (dealt with in article

101 TFEU)

− Abuse of a dominant position by an undertaking (dealt with in article 102 TFEU)

− Mergers and proposed acquisitions and joint-ventures (dealt with in the Council

regulation 139/2004 EC also known as the European Merger Control Regulation)

− State Aid, i.e. aid given by a Member State to companies within its jurisdiction (mainly

dealt with in article 107-108 TFEU).

1

This master thesis will focus on article 101 TFEU and discuss extensively the issue of information

exchange through the tool of benchmarking. Article 101 TFEU reads as follows:

1. The following shall be prohibited as incompatible with the internal market: all agreements

between undertakings, decisions by associations of undertakings and concerted practices which

may affect trade between Member States and which have as their object or effect the prevention,

restriction or distortion of competition within the internal market, and in particular those which:

(a) directly or indirectly fix purchase or selling prices or any other trading conditions;

(b) limit or control production, markets, technical development or investment;

(c) share markets or sources of supply;

(d) apply dissimilar conditions to equivalent transactions with other trading parties, thereby

placing them at a competitive disadvantage;

(e) make the conclusion of contracts subject to acceptance by the other parties of

supplementary obligations which, by their nature or according to commercial usage, have no

connection with the subject of such contracts.

2. Any agreements or decisions prohibited pursuant to this article shall be automatically

void.

3. The provisions of paragraph 1 may, however, be declared inapplicable in the case of:

- any agreement or category of agreements between undertakings,

- any decision or category of decisions by associations of undertakings,

- any concerted practice or category of concerted practices,

which contributes to improving the production or distribution of goods or to promoting

technical or economic progress, while allowing consumers a fair share of the resulting benefit,

and which does not:

(a) impose on the undertakings concerned restrictions which are not indispensable to the

attainment of these objectives;

(b) afford such undertakings the possibility of eliminating competition in respect of a

substantial part of the products in question. (emphasis added)

Article 101 TFEU prohibits agreements between undertakings, decisions by associations of

2

undertakings or concerted practices which negatively affect competition on the market. The form of

these arrangements does not really matter. We can nevertheless distinguish between horizontal and

vertical cooperation agreements. Horizontal agreements concern 'dealings between parties at the

same level of the production and distribution chain'1 whereas vertical agreements are arrangements

'(…) reached between undertakings at different levels of the production and distribution chain'.2

The goals pursued by article 101 TFEU are not totally clear. It has often been assumed that

consumer welfare was the final objective of EU policy.3 Nevertheless, the creation of an Internal

Market without borders 4 or the protection of the structure of the market 5 have also got strong

support from the Court.

It should be noted that the application of EU Competition Law is triggered by the outcome of the

behaviour of an undertaking on the market. Hence, one does not need to prove the existence of a

specific (possibly written) agreement whose object would be to restrict competition in a market.

Similarly, the mere fact that an agreement does not foresee an explicit restriction of trade does not

render it legal per se. The Commission being only concerned with the actual effects of an

agreement, the well-known distinction between agreements having as their object or their effect a

restriction of trade within the Union is mainly one of form and procedure. Is the agreement

explicitly providing for a collusive outcome, it will have as its object a restriction of competition

and the Commission will not have to investigate its effects on the relevant market.6 Otherwise, the

Commission will have to conduct its own investigations.

From the foregoing it appears that concerted practices (or meetings of the minds) have the same

potential to harm competition as explicit agreements. In that sense, they are as much likely to be

caught under article 101 TFEU. Nonetheless, as noted by Van Gerven and Navarro Varona it is

much more difficult to detect them because it is particularly hard or even impossible to demonstrate

1 See PJ Slot and A Johnston, An Introduction To Competition Law (First Edition, Hart Publishing, 2006) p. 91.

2 Ibid

3 See for instance the 2004 Guidelines on the application of article 81(3) of the Treaty [now 101(3) TFEU], [2004] OJ

C-101/97 at para. 13: 'The objective of article 81 [now 101] is to protect competition on the market as a means of

enhancing consumer welfare and of ensuring an efficient allocation of resources. Competition and market

integration serve these ends since the creation and preservation of an open single market promotes an efficient

allocation of resources throughout the Community for the benefit of consumers'.

4 See for instance Cases C-56-58/64, Etablissements Consten SA & Grundig-Verkaufs-GmbH v Commission (Consten

& Grundig) [1966] ECR 299.

5 See Cases C-501, 513, 515 & 519/06 P, GlaxoSmithKline, at para. 61: '(…) article [101 TFEU] aims to protect not

only the interests of competitors or of consumers, but also the structure of the market and, in so doing,

competition as such'. (emphasis added)

6 See the Guidelines on art. 81(3) EC [now 101(3) TFEU], supra at 3, at para. 21: practices that ‘have such a high

potential of negative effects on competition that it is unnecessary (…) to demonstrate any actual effects on the

market’.

3

collusion from market data alone.7 The Commission thus has to focus on finding documentary

evidence of cooperation. In Thyssen Stahl AG v Commission, the European Court of Justice (ECJ)

discussed the nature of concerted practices under article 81(1) EC (now article 101(1) TFEU) in the

following terms:

82. The criteria of coordination and cooperation necessary for determining the existence of a

concerted practice, far from requiring an actual plan to have been worked out, are to be

understood in the light of the concept inherent in the provisions of the EC and ECSC Treaties on

competition, according to which each trader must determine independently the policy which it

intends to adopt on the common market and the conditions which he intends to offer to his

customers (...)

83. While it is true that the right of independence does not deprive traders of the right to adapt

intelligently to the existing or anticipated conduct of their competitors, it does, however, strictly

preclude any direct or indirect contact between such traders, the object or effect of which is

to create conditions of competition which do not correspond to the normal conditions of the

market in question, regard being had to the nature of the products or services offered, the size and

number of the undertakings and the volume of the said market (...)’ (emphasis added)8

More recently, the T-Mobile Netherlands B.V. case confirmed the strict approach already advocated

by the ECJ in Thyssen Stahl AG. The Court affirmed that even a one-time exchange of information

on future market conduct among competitors could amount to a concerted practice prohibited under

article 101 TFEU. 9 Moreover, it put it that there was no need to prove an actual restriction of

competition on the market to find a concerted practice. The underlying idea was that an information

exchange, capable of removing uncertainties relating to the future behaviour of competitors, could

be deemed anticompetitive for this reason alone.10

An efficient way for companies to coordinate behaviour is to maintain regular contact between

themselves. Through such contacts they will be able to exchange past, present and (possibly) future

7 See G van Gerven and E Navarro Varona, 'The Wood Pulp Case and the Future of Concerted Practices', CMLR 31,

1994, pp. 575-608.

8 See Case C-194/99, Thyssen Stahl AG v Commission [2003] ECR I-10821.

9 See Case C-8/08, T-Mobile Netherlands B.V. and Others v Raad van bestuur van de Nederlandse

Mededingingsautoriteit [ECR] I-4529 at para. 62.

10 Ibid, at para. 43.

4

sensitive data. 11 In a 2001 paper, Kühn gave the following definition of information exchange

agreements:

Information exchange agreements are arrangements between firms in which they exchange data

about the current state of the market or about past behaviour but not about future intended conduct.

(…) the information exchanged is based on actions or data that are in principle available and

verifiable for the parties.12

At first sight it would seem counter-productive to prohibit information exchanges in a market.

Indeed, the classical theory of perfect competition (from Adam Smith to Alfred Marshall)13 has put

great emphasis on free and immediate access of firms (and consumers) to information. Knowing all

parameters (input costs, labour...) within a market, economic actors are in a better position to take

rational decisions that will optimize their profits and eventually benefit consumers.14

The Danish government used this assumption when it decided to introduce a mechanism of frequent

publication of prices (firm-specific transaction prices for two grades of ready-mixed concrete) in

order for customers to know which firm had the best prices. This is known as the Danish readymixed concrete case.15 Unfortunately, the scheme did not work the way it should have and within a

short period of time (around 6 months), prices increased of about 20%. It seems that, thanks to the

new price publication mechanism, firms were able to infer their competitors' costs more easily.

Having increased their knowledge of market conditions, it was possible for firms to coordinate their

behaviours.

How to explain the gap between the policy expectations of the Danish government and the

outcomes of the scheme on the market? The answer lies in the representation one has of the market

at hand. Within a static model with only one (unlimited) period, a firm will lower its costs because

11 Ibid, at para. 43: 'An exchange of information between competitors is tainted with an anti-competitive object if the

exchange is capable of removing uncertainties concerning the intended conduct of the participating undertakings'.

12 See KU Kühn, 'Fighting collusion by regulating communication between firms', Economic Policy, April 2001,

p.187.

13 See GJ Stigler, 'Perfect Competition, Historically Contemplated' in Essays in the History of Economics (University

of Chicago Press, Chicago 1965).

14 See BR Henry, ‘Benchmarking and Antitrust’, Antitrust L.J. 62, 1993-1994, p.491: 'When buyers know the full

range of market opportunities, they can purchase from sellers with the lowest prices and force inefficient high-prices

sellers out of the market. When sellers are fully apprised of market factors, they can minimize their costs, adopt

innovative techniques, and lower prices to attract buyers on a competitive basis'.

15 For an extensive study of this case, see PB Overgaard and HP Møllgaard, 'Information Exchange, Market

Transparency and Dynamic Oligopoly', Economics Working Paper 2007-3, University of Aarhus, School of

Economics and Management, April 2007 and S Albæk, HP Møllgaard and PB Overgaard, 'Government-assisted

Oligopoly Coordination? A Concrete Case', The Journal of Industrial Economics, Vol. XLV, No. 4, December 1997.

5

perfect information being secured, it will immediately benefit from an increased amount of

costumers looking for some bargains. Simultaneously it will also trigger a price war for the benefit

of the consumers.16 Yet, market players are actually evolving in a dynamic environment. In that

sense, it could be said that interactions on a market occur in a repeated fashion, i.e. through a series

of periods or games. A price-cut in one period will still help a firm attract customers but will also

trigger retaliation (from competitors) in the following period. Moreover, there is an equilibrium

corresponding to each period. Thus, starting a price war is not desirable because it will only lead to

a new (and less profitable) equilibrium (or the forced exit from the market) in the next period. In the

example given, firms did not use the increased amount of information as an incentive to cut their

prices. Rather, gauging their competitors' costs, they came to an implicit agreement whereby a new

equilibrium at a higher price would benefit them all. Had one firm tried to cut its prices, it would

have faced retaliatory steps from its competitors, rendering such 'maverick' behaviour meaningless.

It has to be noted that not every piece of information proves useful when it comes to taking critical

business decisions (we will discuss this in greater detail in the first chapter of this thesis).

Nevertheless, the larger the amount of information exchanged between undertakings, the better they

will be able to understand a market that has become more transparent. In that respect, it has been

mentioned several times by the Commission that an increased market transparency (obtained

through information exchanges) would be detrimental to competition. In the Wood Pulp case it

stated that the market had been made artificially transparent17 simply by the fact that the prices

quoted by the firms to which this decision was addressed were made known so early.18 Moreover,

Kühn and Vives note that:

Normal competitive conditions are characterized according to the Commission by indirect

information transmission about prices through customers (…) information normally passes from

one producer to another in a multi-stage process: from the producer to his agent or subsidiary, from

the agent of subsidiary to the customer, from the customer to the agent of subsidiary of another

producer who is ultimately informed and then makes his own announcement.19

16 Such a model has been formulated by Sweezy as a 'kinked demand curve'.

17 KU Kühn and X Vives in 'Information Exchanges among Firms and their Impact on Competition', Office for

Official Publications for the European Community, Luxembourg, 1995 discuss and discard a benchmark of 'normal

transparency' by opposition to the 'artificial transparency' mentioned by the Court of Justice.

18 See Joined Cases C-89, 104, 114, 116, 117, 125, 126, 127, 128 and 129/85, Ahlström Osakeyhtiö and Others v

Commission (WoodPulp) [1993] ECR-I-1307 at para. 61.

19 See KU Kühn and X Vives, supra at 17, p. 78.

6

For this reason, information exchanges between competitors (through the means of ad hoc

agreements or not)20 are of the greatest interest for the Commission, as demonstrated for instance by

the UK Tractors Exchange case.21

This does not mean that all information exchange agreements will be deemed illegal per se, as these

can prove economically efficient. This is best demonstrated within the banking and insurance sector

where precise information about (potential) customers is shared among companies in order to

reduce the likelihood of information asymmetry and to eliminate the lock-in effect of customers not

daring to switch between companies because they do not want to lose the benefit conferred e.g. by

their long driving period without accident.

Even if the move towards a greater willingness to assess all beneficial effects stemming from

information sharing agreements is quite recent, it does not mean that the Commission has only

lately recognized the efficiency-enhancing effects of such arrangements. Indeed, as early as 1968

the Commission issued a Notice on Cooperation Agreements where it drew up a list of practices that

could be seen as beneficial and thus unlikely to infringe article 81(1) EC (now article 101(1)

TFEU). 22 This list included among others exchanges of opinion or experience, joint market

research, joint carrying out of comparative studies of enterprises or industries and joint preparation

of statistics and calculation models. The Commission defined its policy in a more detailed way in its

1978 Seventh Report on Competition Policy.23 Therein it insisted on the necessity to conduct a caseby-case analysis where the structure of the relevant market (oligopoly/ atomized market) and the

nature of the data exchanged (public/private, aggregated/individualized) would be essential factors

in reaching a decision. Thus, the Commission was already concerned with companies' own

information on prices, sales conditions, input and output whereas industry-wide data that amount to

statistics were seen as relatively harmless.

20 See the Guidelines on the application of Article 101 TFEU of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union

to horizontal co-operation agreements, [2011] OJ C-11/1, at para. 60:

'The criteria of coordination and cooperation necessary for determining the existence of a concerted practice, far

from requiring an actual plan to have been worked out, are to be understood in the light of the concept inherent in

the provisions of the Treaty on competition, according to which each company must determine independently the

policy which it intends to adopt on the internal market and the conditions which it intends to offer to its

customers'. (emphasis added)

21 We will discuss this case in the first chapter of this thesis.

22 See the Notice on Cooperation Agreements, [1968] JO C-75/3, [1968] CMLR D5.

23 See the Seventh Report on Competition Policy, Brussels-Luxembourg, April 1978.

7

In a 2004 paper, Nitsche and von Hinten-Reed identified a series of potential advantages stemming

from information sharing agreements. 24 Referring to the works of Christiansen and Caves who

investigated information exchanges relating to capacity expansion in the pulp and paper industry,25

they concluded that in certain cases investment decisions were less uncertain thanks to the use of

non-binding information exchange (or ‘cheap talk’) between competitors. As a result, economic

efficiency and ultimately global welfare was improved. Drawing on the seminal work of Kühn and

Vives,26 this paper further underlined other possible efficiency-enhancing effects. One of them is

output adjustment. According to the authors, quantity adjustment will benefit both producers and

consumers who will not have to bear producers' extra costs stemming from too high/too low

production. Another benefit is the lowering of search costs (as extensively explained by Georges

Stigler in his 1961 article on 'The Economics of Information').27

In Evans and Mellsop's 'Exchanging Price Information can be Efficient, Per Se Offences Should be

Legislated very Sparingly' (2003), we find another possible welfare-enhancing outcome of

information exchanges, namely the mitigation of the ‘winner's curse’. 28 29

Benchmarking is a tool used by undertakings to exchange information among themselves in an

efficiency-enhancing perspective. If it is praised by the business literature, it has been seen more

critically by lawyers. Let us now observe this practice in more details.

In order to meet the needs of their customers firms need to be very responsive and to adapt

continually to an evolving environment. Some companies seem to detect more effectively what will

be the next (business) trends on a market and even act as trendsetters. Other firms simply try to

follow these trends. In order for the latter to be/remain efficient on a market, they need to get

inspiration from other companies' good practices. At the same time, best-in-class companies want to

retain their competitive advantage by ameliorating their practices. Providing this information is the

aim of benchmarking.

24 See R Nitsche, N von Hinten-Reed, ‘Competitive Impacts of Information Exchange’, Charles River Associates,

2004.

25 See LR Christiansen, RE Caves, 'Cheap Talk and Investment Rivalry in the Pulp and Paper Industry', Journal of

Industrial Economics 45, No. 1, March 1997, pp. 47-53.

26 See KU Kühn and X Vives, supra at 17.

27 See GJ Stigler, 'The Economics of Information', The Journal of Political Economy 69, No. 3, June 1961, pp. 213225.

28 See L Evans, J Mellsop, 'Exchanging Price Information can be Efficient: Per Se Offences Should be Legislated very

Sparingly', Mimeo, Victoria University of Wellington, 2003.

29 In short, the winner's curse can be described as the phenomenon that leads the winner of a common value auction

with incomplete information to overpay for his good. Through information exchange this outcome will be less

likely.

8

Benchmarking can thus be described as '(...) the process of measuring the performance of one's

company against the best in the same or another industry'.30 '(...) the objectives of this exercise are

(1) to determine what and where improvements are called for, (2) how other firms achieve their

high performance levels, and (3) use this information to improve the firm's performance'.31

In that sense, benchmarking is the stereotype of an information-sharing agreement with a high

efficiency-enhancing potential. Yet, it poses a challenge to the competition authority because of the

risks it entails.

In this thesis, we will carefully examine the benchmarking methodology in order to see how it fits

within the competition provisions of EU Law (in particular the 2010 Guidelines on Horizontal

Cooperation Agreements). Our aim will be to assess the potential for reconciliation between these

two conflicting items in order to profit from both a high level of competition in the market and the

benefits stemming from the sharing of best business practices.

In that respect, our first chapter will be dedicated to a thorough analysis of the latest developments

on information sharing within the EU. We will then review the benchmarking practice and pinpoint

the features that could potentially breach EU Law. Finally, we will try to reconcile the EU policy on

information sharing and the benchmarking tool by suggesting guidelines for benchmarking staffs

and arrangements for policy-makers.

30 See Stevenson, 1996, quoted by WM Lankford in 'Benchmarking: understanding the basics', The Coastal Business

Journal 1, Number 1, p 57.

31 Source: <http://www.businessdictionary.com/definition/benchmarking.html>, accessed 3 April 2011.

9

10

Chapter I

How does EU Competition Law understand exchanges of information?

Section 1: Introduction to the new Guidelines on Horizontal Cooperation Agreements

Because they have the potential to lessen competition in a market by acting as concerted practices

allowing competitors to align their behaviours, information exchange agreements are under the

Commission's scrutiny. It nevertheless does want to distinguish between genuine efficiencyenhancing agreements and collusive covenants in disguise.

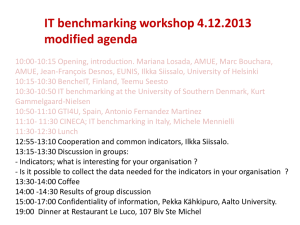

This care is best demonstrated by the newly issued Guidelines on the applicability of article 101

TFEU to horizontal cooperation agreements of 14 December 2010 (‘the Guidelines’).32 Whereas

the previous version33 was not even concerned with information exchange and did not mention the

term “benchmarking”, 34 the current Guidelines devote thirteen pages to this issue and the word

‘benchmark/ing’ is mentioned 5 times throughout the whole document.

In the light of this soft law instrument 35 what is then the current policy regarding information

exchanges within the European Union?

To begin with, it is worth mentioning the ambits of the Commission. In the introduction, it is thus

stated that the Guidelines will apply to all sorts of cooperation agreements of 'a horizontal nature',

regardless of the fact that these may be entered into by competitors or by non-competitors. As an

example of non-competitors, the Commission mentions '(...) two companies active in the same

32 Commission, Guidelines on the applicability of Article 101 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union

to horizontal co-operation agreements, [2011] OJ C-11/1.

33 Commission, Guidelines on the applicability of Article 81 of the EC Treaty to horizontal cooperation agreements,

[2001] OJ C-3/2.

34 The Commission had nevertheless addressed this issue in a 2006 Information Note, ‘Issues raised in discussion with

the carrier industry in relation to the forthcoming Commission Guidelines on the application of competition rules to

maritime transport services’. However its scope was much narrower than what is been dealt with in the new 2010

Guidelines. Yet, one can there discern the basis for the current Guidelines. Indeed the Commission stated its

intention to look at the nature and type of information exchanged, the level of aggregation of the information, the

period to which it relates, the frequency of exchange and the delay of release of the data.

35 Together with other like-instruments Guidelines are “soft law” in the sense that they give guidance but do not bind

the ECJ in its appreciation of a case.

11

product market but in different geographic markets without being potential competitors'. 36 It

develops by stating the potential danger of such agreements:

The potential effect of such agreements may be the loss of competition between the parties to the

agreement. Competitors can also benefit from the reduction of competitive pressure that results from

the agreement and may therefore find it profitable to increase their prices. The reduction in those

competitive constraints may lead to price increases in the relevant market (…)37

The Commission then pinpoints two possible outcomes of a horizontal cooperation agreement, the

first relating explicitly to information exchange agreements:

A horizontal co-operation agreement may also:

−

lead to the disclosure of strategic information thereby increasing the likelihood of

coordination among the parties within or outside the field of co-operation' 38 (emphasis

added)

Part 2 of the Guidelines then goes into more details on information exchanges, that it divides into

two categories: i.e. 'data (…) directly shared between competitors' and 'data shared indirectly

through a common agency (like a trade association) or a third party such as a market research

organisation of through the companies' suppliers or retailers'.39

Subpart 2 is concerned with the assessment of information exchanges under article 101(1) TFEU.

Basically, we can observe two possible threatening outcomes pertaining to the aforementioned

agreements.

The first one relates to a collusive outcome. Thanks to the (strategic) information they have

exchanged, firms active in a market will be able to better understand their competitors' economic

situation and possibly (better) predict their behaviour in the near future. Coordination appears (the

Guidelines speak about alignment) and this logically leads to restrictive effects on competition.

36

37

38

39

See the 2010 Guidelines, supra at 32, at para. 1.

Ibid, at para. 34.

Ibid, at para. 35.

Ibid, at para. 55.

12

Information exchanges are often referred to as ‘facilitating practices’. In a 2004 paper Donatella

Porrini defines them in the following terms:

We can define as facilitating, various practices like information exchanges that try to limit the

influence of factors that destabilize co-operative outcomes and enhance the factors that support cooperative outcomes. So, even if information-sharing in itself is not a restriction on competition, the

competition authorities can concentrate on detecting specific information exchanges in their role of

40

sustaining explicit and tacit collusion.

Collusion can occur through different channels. Through information exchange companies can

'reach a common understanding of the terms of coordination',41 what in turns will 'create mutually

consistent expectations regarding the uncertainties present in the market'.42 In brief, 'exchange of

information about intentions concerning future conduct is the most likely means to enable

companies to reach such a common understanding'.43 Moreover, information exchange is likely to

reinforce the stability of a possible existing cartel by 'enabling the companies involved to monitor

deviations' 44 more easily. This is made possible after the market has become more transparent

thanks to the better understanding companies have of each other's behaviour. Finally, an increased

transparency in the market will also allow colluding companies to detect firms that are willing to

enter the market and to prevent them from doing so.

The second concern is about anti-competitive foreclosure. Let us imagine that we have an

information exchange agreement entered into only by a few (possibly dominant) firms in the

market. The remaining firms that do not benefit from an increased amount of information will then

be placed at a comparative disadvantage. Logically, such an outcome can only be foreseen 'if the

information concerned is very strategic for competition and covers a significant part of the relevant

market'.45

40 See D Porrini, 'Information Exchange as Collusive Behaviour: Evidence from an Antitrust Intervention in the Italian

Insurance Market', The Geneva Papers on Risk and Insurance 29, No. 2, April 2004, pp. 219-233.

41 See the 2010 Guidelines, supra at 32, at para. 66.

42 Ibid.

43 Ibid.

44 Ibid, at para. 67.

45 Ibid, at para. 70.

13

The Guidelines then go on by assessing the likelihood of competition concerns taking into account

the structure of the market at hand and the characteristics of the information exchange mechanism.46

Section 2: Market characteristics that favour a collusive outcome stemming from an

information exchange agreement (assessment under article 101(1) TFEU)

Let us first look at the market characteristics. Paragraph 77 states that:

(…) companies are more likely to achieve a collusive outcome in markets which are sufficiently

transparent, concentrated, non-complex, stable and symmetric. In those types of markets companies

can reach a common understanding on the terms of coordination and successfully monitor and

punish deviations (...)'

The fact that a market does not fulfil these conditions does not mean that no collusive outcome will

ever appear in it. In that sense, the Guidelines emphasize that 'a collusive outcome [can also be

achieved] in other market situations where they [note: the companies] would not be able to do so in

the absence of the information exchange'. 47 Thus 'the competitive outcome of an information

exchange depends not only on the initial characteristics of the market in which it takes place (such

as concentration, transparency, stability, complexity, etc.) but also on how the type of the

information exchanged may change those characteristics'.48 We will see this aspect in Section 3.

A last point has to be made before assessing market characteristics: information exchanges between

firms that are not direct competitors will not raise (major) antitrust concerns. The only risky

situation would be that of an information exchange between a supplier and its dealers. This would

however be dealt with under the Guidelines on Vertical Cooperation Agreements

46 This is in line with the previous case law of the ECJ in Case C-238/05, Asnef-Equifax, Servicios de Información

sobre Solvencia y Crédito, SL v Asociación de Usuarios de Servicios Bancarios (Ausbanc) [2006] ECR I-11125, at

para. 54: 'Accordingly (...) the compatibility of an information exchange system (...) with the [EU] competition rules

cannot be assessed in the abstract. It depends on the economic conditions on the relevant markets and on the specific

characteristics of the system concerned, such as, in particular, its purpose and the conditions of access to it and

participation in it, as well as the type of information exchanged—be that, for example, public or confidential,

aggregated or detailed, historical or current—the periodicity of such information and its importance for the fixing of

prices, volumes or conditions of service'.

47 See the 2010 Guidelines, supra at 32, at para. 77.

48 Ibid.

14

§1: Transparency

Transparency and concentration of a market are factors that are intuitively felt as being potentially a

threat for competition. We already mentioned the relevance of market transparency as a means to

monitor possible deviations and attempts of new firms to enter the cartelized market.49

§2: Concentration

Concentration is closely related to transparency. The Guidelines mention that 'tight oligopolies can

facilitate collusive outcomes on the market as it is easier for fewer companies to reach a common

understanding of the terms of coordination and to monitor deviations'.50

With more firms acting in the market, we are going towards an atomized structure of the market, i.e.

each firm's market share is decreasing. Whereas an information exchange within an oligopoly

allows for an easier identification of each firm's behaviour, this cannot be done within an atomized

market. Hence, a firm's deviation from the cartel (e.g. by undercutting its prices) will not be easily

detected, rendering deviation even more profitable. Moreover, as mentioned by the Guidelines

'gains from the collusive outcome are smaller because, where there are more companies, the share

of the rents from the collusive outcome declines'.51

This can be seen in the UK Tractors case52. This landmark suit, the first that was brought by the

Commission against an information sharing agreement alone (no collusion had been demonstrated),

shows that within a small and stagnant market, with high concentration (the four biggest firms had a

combined market share of about 80%), high barriers to entry and high customer loyalty, information

that would otherwise seem inoffensive turns into particularly valuable data. In the words of the

Commission:

The exchange restricts competition because it creates a degree of market transparency between the

suppliers in a highly concentrated market which is likely to destroy what hidden competition there

remains between the suppliers in that market on account of the risk and ease of exposure of

independent competitive action. In this highly concentrated market, ‘hidden competition’ is

essentially that element of uncertainty and secrecy between the main suppliers regarding market

49 See also J Green and R Porter, 'Non-cooperative collusion under imperfect price information', Econometrica 52, No.

1, 1984, pp. 87-100.

50 See the 2010 Guidelines, supra at 32, at para. 79.

51 Ibid.

52 See UK Agricultural Tractor Registration Exchange [1992] OJ L 68/19; [1993] 4 CMLR 358. Confirmed by the

General Court and the Court of Justice: see case T-35/92 J Deere v. Commission [1994] ECR II-957.

15

conditions without which one of them has the necessary scope of action to compete efficiently.

Uncertainty and secrecy between suppliers is a vital element of competition in this kind of market

(emphasis added).

Albeit theoretically well founded, the Guidelines' outcomes are of little help when it comes to

policy implications. Indeed, how to assess if collusion is likely or unlikely to appear within a given

market structure? Are there any figures available?

Apparently, this (fairly practical) question has attracted little attention from game-theory

economists, probably because it implies an analysis within a static environment, which renders it ill

fitted for actual (dynamic) market conditions. In a 1973 article, Selten explains that the number of

firms will be critical if it is between four and six.53 With four or less firms in the market the

likelihood of collusion will reach its maximum, whereas with six or more firms, it will quickly

decrease to its minimum. According to Sherer and Ross the minimum could be reach with a number

of ten to twelve firms in the market. 54 Even if it looks appealing, this model has to be used with

care. In fact, it presupposes a situation where firms agree to cooperate without trying to cheat

(Pepperkorn speaks of a 'cooperative game with enforceable agreements'). 55 Again, this is hardly

the case in the real world where strategies is highly volatile.

§3: Complexity

Complexity of the market is also a relevant factor when assessing the collusive outcomes of an

information exchange agreement. In order for firms to agree on prices or collusive conditions, i.e. to

propose similar sales conditions to potential buyers, they first need to produce similar products. You

cannot create a cartel in the automobile industry and propose the same price for city cars and SUVs.

Hence, in a complex market structure with high product differentiation, collusive outcomes seem

unlikely to appear. The Guidelines nevertheless foresee a situation where firms, instead of

exchanging information about a wide range of products and prices, simply agree on some basic

53 See R Selten, 'A simple model of imperfect competition where four are few and six are many', International Journal

of game Theory 2, 1973, pp. 141-201.

This article is mentioned by L Peeperkorn in 'Competition Policy Implications from Game Theory: an Evaluation of

the Commission's Policy on Information Exchange'. Paper presented at the CEPR/European University Institute

Workshop on Recent Developments in the Design and Implementation of Competition Policy, Florence, 29

November 1996. Peeperkorn also mentions two works of L Phlips, Competition Policy: a game-Theoretic

Perspective (CUP, Cambridge, 1995) and 'On the Detection of Collusion and Predation', European Economic

Review 40, pp. 495-510.

54 See FM Sherer and D Ross, Industrial Market Structure and Economic Performance (Third Edition, Houghton

Mifflin Company, Boston, 1990).

55 See L Pepperkorn, supra at 53.

16

pricing rules like pricing points. This would certainly be a concern for DG Comp.

§4: Stability of demand and supply conditions

As the Guidelines mention: 'in an unstable environment it may be difficult for a company to know

whether its lost sales are due to an overall low level of demand [note: for instance because of the

introduction of a new technology] or due to a competitor offering particularly low prices. Therefore

it is difficult to sustain a collusive outcome'.56 Because innovation is often brought by outsiders,

erecting significant barriers to entry 'would make it more likely that a collusive outcome on the

market is feasible and sustainable'.57

In the case of a dynamic market driven by innovation, homogeneity of products is hard to achieve

(and it is certainly not what companies are aiming at). By introducing a new item on the market

(thanks to a technological leap) a company may be wanting to reduce the price of its older range of

products, possibly to target new customers. However, when confronted to lost sales competitors will

find it hard to analyse the rationale behind them, as they could be explained both by a price cut or

the new technology.

§5: Symmetry

Paragraph 82 of the Guidelines goes on with the criteria of symmetry:

(…) a collusive outcome is more likely in symmetric market structures. When companies are

homogeneous in terms of their costs, demand, market shares, product range, capacities, etc., they are

more likely to reach a common understanding on the terms of coordination because their incentives

are more aligned.

However, one cannot rule out that through information exchange, firms will be able to (better)

accommodate their differences. Related to this is the nature of the goods present in the market. If

these are substitutes (an increased demand for one good would decrease demand for the other), the

collusive outcome of an agreement will not be the same than if goods are complements (an

increased demand for one good would increase demand for the other).

56 See the 2010 Guidelines, supra at 32, at para. 81.

57 Ibid.

17

§6: Long-lasting commercial relationships

Finally, a collusive outcome is more likely to happen when firms maintain long-lasting commercial

relationships and 'continue to operate in the same market for a long time'.58 A company will be less

willing to deviate for a cartel behaviour if it knows that the gain it will derive from the deviation at

a certain point of time will not outbalance the future losses resulting from its price cut and the

retaliation from the remaining colluding firms. This once more highlights the importance of a

credible and prompt retaliation mechanism in order to sustain collusion. The Guidelines state that

'the credibility of the deterrence mechanism also depends on whether the other coordinating

companies have an incentive to retaliate, determined by their short-term losses from triggering a

price war versus their potential long-term gain in case they induce a return to a collusive

outcome'.59

Section 3: Characteristics of the information exchange that favour a collusive outcome

(assessment under article 101(1) TFEU)

Having in mind the characteristics of a market that would facilitate collusion, let us now look at the

characteristics of the information exchange itself. Paragraph 86 to 94 of the Guidelines underline

seven relevant factors that have to be taken into consideration: the strategic nature of the

information, the coverage of the market, the individualization of the data, the age of the data, the

frequency of the information exchange, the publicity of the information and finally the publicity of

the information exchange.

First, it should be recalled that information is a “catch-all” term, that refers to a host of different

sub-categories. According to the New Oxford American Dictionary, it can be described as 'facts

provided or learned about something or someone'. Thus, as with all facts (or data in our case), some

will finally prove useful and some not. Information can then be divided into two categories:

strategic (or business-relevant) information and non-strategic (thus inoffensive) information.

58 Ibid, at para. 84.

59 Ibid.

18

§1: Strategic nature of the information

The Commission understands strategic information as 'data that reduces strategic uncertainty in the

market'.60 It can be related to prices (plus discounts or price evolution),61 customer lists, production

costs, quantities, turnover, sales, capacities, qualities, marketing plans, risks, investments,

technologies and R&D programmes. The Re Cimbel case62 shows that strategic information is not

only related to prices. In this case the Commission condemned an information exchange agreement

on projected increases in industrial capacities. The result of such information sharing was that a

firm could not take benefit of a sudden increase in demand by intelligently adapting its capacities to

it and thus growing accordingly. All firms being able to respond simultaneously to such increases in

demand, the relative market shares would stay the same, thus triggering a status quo or collusion. In

the same fashion the Commission condemned the obligation to inform rivals of investment plans

(Zinc Producer Group case).63

The Commission was also concerned with the nature of the information actually exchanged in the

aforementioned UK Tractors case.64

The information exchange scheme provided for the sharing of sales volumes of manufacturers and

importers of agricultural tractors in the United Kingdom. Information was highly detailed and

comprised the 'distributor's name and address, the tractor's serial number, the exact sales volume

and the market share by model and horsepower category, at national, regional and county level'.65

Kühn mentions that 'given the size of the postal code area this information allows the firms in the

industry to identify almost all individual tractor sales'. 66 One of the firms taking part in the

agreement argued that in addition to some efficiency gains (with regards to the processing of

possible warranty claims and the monitoring of the performance of sales personnel), the scheme

could not harm competition because it related to past conducts. Kühn disagrees with this argument

and emphasizes the relevance of this specific information within the market for tractors in the UK.

60 Ibid at para. 86.

61 In VNP/COBELPA, OJ [1977] L-242/10, [1973] 2 CMLR D28; the ECJ states that information becomes particularly

strategic (and hence should not be exchanged) when it is 'usually kept strictly confidential'.

62 See Re Cimbel, OJ [1972] L-303/24, [1973] CMLR D167.

63 See Zinc Producer Group, OJ [1984] L-220/27, [1985] 2 CMLR 108.

64 Supra at 52.

65 See John Deere Ltd v. Commission, T-35/92 [1994] ECR II-957 at para. 14-21.

66 See K-U Kühn, 'Fighting collusion by regulating communication between firms', Economic Policy, April 2001, p

194.

19

He writes that firms are willing to organize bidding rings and that 'the identification of individual

tractor sales is under such circumstances exactly the type of information that the firms would like to

have to organize such bidding rings'. 67 The conclusion of the Commission is therefore not

surprising: 'own company data and aggregate industry data are sufficient to operate in the

agricultural tractor market'.68

Thus, information about prices, quantities, costs, 69 business planning, wages 70 and demands is

particularly strategic for undertakings and it will be reviewed carefully and critically by DG

Comp.71

In a 2006 article Whish discusses the impact of the nature of the information exchanged on

competition within a market.72 He mentions the Re VNP and COBELPA case:

(…) whilst it is permissible to exchange general statistical information which could give a picture of

aggregated sales and output in an industry without identifying individual companies, it would be

contrary to article 81(1) EC for firms to provide competitors with detailed information about matters

which would normally be regarded as confidential.73

In a 2004 article: ‘Competitive Impacts of Information Exchange’, Nitsche and von Hinten-Reed

discuss the per se interdiction of the exchange of individualized pricing and quantity data.

Mentioning recent case studies on collusive arrangements, they write that '(...) effective collusion

requires agreement and monitoring or much more than just the ‘price' or the 'quantity'’.74 Thus it

may well be possible to allow information exchange on a price or a quantity if further details are not

67 See K-U Kühn, supra at 66, p. 194.

68 See UK Agricultural Tractor Registration Exchange, supra at 52, at para. 62.

69 As argued by BR Henry, supra at 14, p. 498: 'Costs are directly related to the ultimate price of a product or service

and the exchange of such information (whether based on past, current or projected future costs) might lead to price

stabilization'.

70 Wages, like other discrete costs, contribute (to a great extent) to the total cost structure. Sharing such information

may lead to an accepted 'standard' wage level that would not foster competitive efforts to attract best personal.

71 The US Supreme Court also sees with a wary eye agreements that lead to exchanges of price information.

See for instance United States v Container Corp., 393 US 333 (1969) at para. 337 where the Court stated that: ‘The

exchange of price data tends towards price uniformity (…) Stabilizing them as well as raising them is within the ban

of section 1 of the Sherman Act (...)'.

72 See R Whish, 'Information agreements' in Konkurrensverket (Swedish Competition Authority), 'The Pros and Cons

of Information Sharing' (Stockholm, 2006).

73 Ibid, p. 31.

74 See R Nitsche and N von Hinten-Reed, supra at 24, pp. 5-6.

20

exchanged'.75

Evans and Mellsop even argue that in certain cases welfare-enhancing effects can flow from an

exchange of price information. 76 Referring to the New-Zealand market for meatpacking where

producers are facing uncertainty about the weekly supply of livestock at any given price and the

price they will finally receive for the processed product, they demonstrate that exchanging data on

prices seemed the best solution to reach an optimal outcome for all the parties concerned. They

conclude that in this specific case the object of the meetings was not to agree on a maximum

transaction price but rather on a minimum transaction price. These information exchanges seemed

to be needed in order to mitigate the winner's curse that was associated with the transaction in this

industry. The absence of a forward market (that was too costly to put into place) was the main

reason why this information exchange was beneficial. In a situation with non-atypical transaction

costs it is however hard to reach the same conclusion.

The views briefly exposed above remind us that the per se prohibition of certain types of

information exchange agreements (e.g. where prices are the core of the agreement) is never entirely

satisfactory because it tends to be ill-fitted to the diversity of agreements that are likely to be

concluded. Should we then go as far as writing that in some cases collusion can enhance welfare?77

We think that even if the economic theory will point to the necessary limits of a per se prohibition

of certain practices, this will still reveal efficient for the vast majority of cases. Moreover, such

prohibition provides the interest parties with some guidelines of what they are allowed to do and

what should not be undertaken. Such a framework is absolutely necessary if one is concerned with

legal certainty.

§2: Market coverage

Another relevant factor is market coverage. In 2001 the Commission issued a Notice on agreements

of minor importance which do not appreciably restrict competition under article 81(1) EC (now

75 Ibid.

76 See L Evans and J Mellsop, supra at 28.

77 This is the position held by C Fershtman and A Pakes in 'A dynamic oligopoly with collusion and price wars', RAND

Journal of Economics 31, No. 2, Summer 2000, pp. 207-236.

21

article 101(1) TFEU) (‘de minimis notice’)78 that provides for thresholds in order to assess such

agreements.79 It is important that firms involved in the exchange have a sufficient market share,

otherwise they risk being constrained by the remaining companies not participating in the

information exchange. Firms that do not fulfil the conditions set out by the de minimis Notice (i.e.

those that do not fall within the so-called ‘safe harbour’), cannot rely on any market share figures

below which their behaviour 80 would be deemed irrelevant and thus legal. In the words of the

Commission in paragraph 87 of the Guidelines: 'what constitutes ‘a sufficiently large part of the

market’ cannot be defined in the abstract and will depend on the specific facts of each case and the

type of information exchange in question'.

§3: Individualization of the information

Another factor that was extensively discussed within the academia before the Commission adopted

its new Guidelines in 2010 is the individualization (or otherwise aggregation) of data. It is

mentioned in the Guidelines that the exchange of aggregated data should normally not lead to

restrictive effects on competition.81

Aggregated data is information that has been compiled so to make it impossible (or sufficiently

difficult) to recognize company level information. By contrast, individualized data is companyspecific information that is particularly valuable for the reasons we already mentioned earlier, i.e.

an easier detection of possible deviations and an easier conception of individual retaliatory

78 See the Commission Notice on agreements of minor importance which do not appreciably restrict competition under

Article 81(1) of the Treaty establishing the European Community [now article 101(1) TFEU] (‘de minimis notice’),

OJ [2001] C 368/13, p.13-15.

79 See for instance para. 7 of the aforementioned notice:

‘The Commission holds the view that agreements between undertakings which affect trade between Member

States do not appreciably restrict competition within the meaning of Article 81(1) [now article 101(1)]:

(a) if the aggregate market share held by the parties to the agreement does not exceed 10 % on any of the

relevant markets affected by the agreement, where the agreement is made between undertakings which are

actual or potential competitors on any of these markets (agreements between competitors); or

(b) if the market share held by each of the parties to the agreement does not exceed 15 % on any of the relevant

markets affected by the agreement, where the agreement is made between undertakings which are not actual or

potential competitors on any of these markets (agreements between non-competitors).

In cases where it is difficult to classify the agreement as either an agreement between competitors or an

agreement between non-competitors the 10 % threshold is applicable’.

80 The Guidelines insist on the fact that the de minimis notice only applies where the information exchange takes place

in the context of another type of horizontal co-operation agreement.

81 This is in line with what was previously said in the Seventh Report on Competition Policy (Brussels-Luxembourg,

April 1978) where we can read that 'the provision of collated statistical material is not in itself objectionable'

whereas 'the organised exchange of individual data from individual firms (…) will normally be regarded by the

Commission as practices (…) which are therefore prohibited'.

22

strategies. Thus the 'collection and publication of aggregated market data (such as sales data, data

on capacities or data on costs of inputs and components) by a trade organisation or market

intelligence firm may benefit suppliers and customers alike82 by allowing them to get a clearer

picture of the economic situation of a sector' (emphasis added).83

Even if the exchange of aggregated data seems efficiency enhancing and thus unlikely to threaten

competition in the market, there are some cases where collusive outcomes could be reached if

specific market conditions are met. The Guidelines mention the example of a tight oligopoly where

a deviation from one of the few firms would immediately be noticed, although the identity of the

‘culprit’ would not be inferred solely from the data. That is, in certain cases the mere observance of

a deviation through aggregated data would be sufficient to trigger retaliatory steps.84 Likewise, in

the Vegetable Parchment case, the Commission stated that:

The regular sending to (…) an association (…) of invoices or other individual data normally

regarded as business confidences would be an indicator of (…) concerted practice [since] for the

preparation of monthly statistics (…) it is sufficient to send only totals from invoices during the

relevant period.85

It thus remarked that the aggregation of data does not constitute a ‘safe harbour’ for firms and that

they have to keep in mind that certain behaviours will be looked at very critically by the

Commission and the ECJ.

One also has to mention the means through which data is been collected, aggregated and shared

among competitors. The Commission will be less concerned if the task is given to a third-party

82 It seems that the Commission only refers to a non-discriminatory disclosure of data by trade associations. K-U Kühn

and X Vives in 'Information Exchanges among Firms and their Impact on Competition', Office for Official

Publications for the European Community, Luxembourg, 1995 make a further distinction between data that will only

be disseminated to the members of the trade association (exclusionary disclosure) and data that will be given to any

interested party (non exclusionary disclosure). If the latter is unlikely to bring competition concerns, the former

should be scrutinized more carefully.

83 See the 2010 Guidelines, supra at 32, at para. 89.

84 This position is also advocated by L Pepperkorn, supra at 53, p. 6. Referring to a model developed by J Green and R

Porter in 1984 he argues that 'below a critical market price level the oligopolists will automatically assume that

someone has cheated and trigger off a price war. This means that aggregate price information could be of use to

oligopolists when trying to collude.'

85 See Vegetable Parchment, OJ [1978] L-70/54.

23

entity, like a trade association, than if it is done by one of the competitors itself.86 This does not,

however, preclude any investigation because, at the end, the information exchange agreement will

be assessed globally taking into account all relevant parameters.

The relevance (for firms) of data that is as disaggregated as possible is demonstrated by the famous

Fatty Acids case.87 In the 1970s the market for fatty acids was dominated by a handful of firms:

Unilever, Henkel and Oleafina, forming a tight oligopoly. Next to these ‘Three Bigs’ were forty

small producers whose capacities were about twenty times lower than the former's ones. A trade

association named APAG88 which accounted for around 90% of the fatty acids market including the

three largest producers operated within the market. This association maintained an information

exchange agreement consisting of aggregated industry data that was in line with the requirements of

EU Competition law on that matter.89 However, another agreement was entered into by the three

largest producers. This agreement appeared likely to restrict competition on the market. It provided

for the exchange of 'individualized data about yearly total sales in the previous three years and

future four-monthly reports about total sales by each of these competitors' (emphasis added).90

Through this mechanism, the three firms were able to monitor each other's individual sales data. As

noted by Kühn, it seems that the plan was to drive small competitors out of the market while

maintaining the relative market shares of the three remaining firms. 91 This can only be done

through the recourse to individualized strategic data and it advocates for the Commission's

precaution when data exchanged is not aggregated.

The Fatty Acids case and the new Guidelines alike advocate for a very orthodox view on the

aggregation of data. Other conclusions have been drawn by Novshek and Thoman in a 1998 paper.

In contrast with Kühn and Vives, 92 they believe that 'when shocks to demand are not perfectly

correlated, firms may have non-collusive incentives to share disaggregated information' (i.e. also

about price and output data).93

86 Similar outcomes can be found in the United States, see for example DOJ, Business Review Letter concerning Hyatt,

Imler, Ott & Blount, P.C (June 12, 1992) – no challenge to a proposal by a public accounting firm in Atlanta to

compile, analyse, and publish data on the prices charged by Georgia hospitals.

87 See Fatty Acids, OJ [1987] L-3/17.

88 Association des Producteurs d'Acides Gras.

89 See the Seventh Report on Competition Policy, Office for Official Publications of the European Communities,

Brussels-Luxembourg, 1978.

90 See KU Kühn, supra at 66.

91 Ibid.

92 See KU Kühn and X Vives, supra at 17.

93 See W Novshek and L Thoman, 'Information disaggregation and incentives for non-collusive information sharing',

Economics Letters 61, 1998, pp. 327-332.

24

Analysing a model in which firms sell the same product in a number of independent regions and do

not coordinate, they write that:

This means that if information is shared as a list of the members' signals, then an anonymous list is

inferior to a non-anonymous list, since firms do not know the weight to attach to a signal without

knowing who received the signal (…) Any other information exchange mechanism (no sharing,

or anonymous disaggregated sharing, or aggregated sharing, either as an overall average or as

market-by-market averages) provides less precise information to firms and is inferior to

consumers' and total surplus (emphasis added).94

§4: Age of the information

Let us now turn to the criterion of the age of the data. This is again particularly decisive because the