Study of Thin Film Solar Cell based on Copper Oxide Substrate by

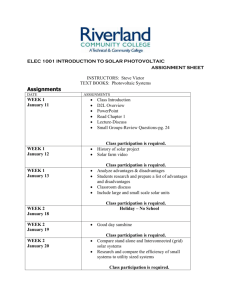

advertisement