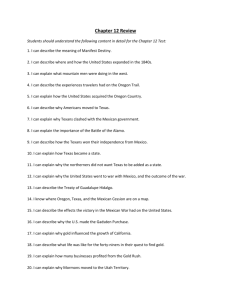

Texas Civil Rights Leaders: White, González, García, Telles

advertisement

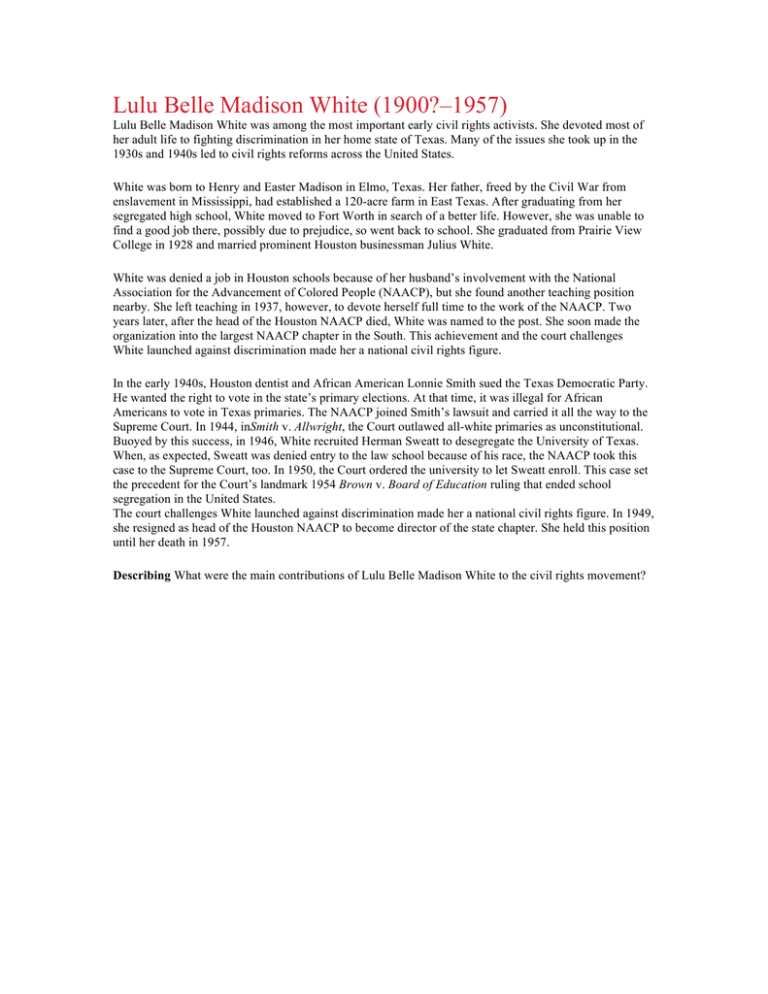

Lulu Belle Madison White (1900?–1957) Lulu Belle Madison White was among the most important early civil rights activists. She devoted most of her adult life to fighting discrimination in her home state of Texas. Many of the issues she took up in the 1930s and 1940s led to civil rights reforms across the United States. White was born to Henry and Easter Madison in Elmo, Texas. Her father, freed by the Civil War from enslavement in Mississippi, had established a 120-acre farm in East Texas. After graduating from her segregated high school, White moved to Fort Worth in search of a better life. However, she was unable to find a good job there, possibly due to prejudice, so went back to school. She graduated from Prairie View College in 1928 and married prominent Houston businessman Julius White. White was denied a job in Houston schools because of her husband’s involvement with the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), but she found another teaching position nearby. She left teaching in 1937, however, to devote herself full time to the work of the NAACP. Two years later, after the head of the Houston NAACP died, White was named to the post. She soon made the organization into the largest NAACP chapter in the South. This achievement and the court challenges White launched against discrimination made her a national civil rights figure. In the early 1940s, Houston dentist and African American Lonnie Smith sued the Texas Democratic Party. He wanted the right to vote in the state’s primary elections. At that time, it was illegal for African Americans to vote in Texas primaries. The NAACP joined Smith’s lawsuit and carried it all the way to the Supreme Court. In 1944, inSmith v. Allwright, the Court outlawed all-white primaries as unconstitutional. Buoyed by this success, in 1946, White recruited Herman Sweatt to desegregate the University of Texas. When, as expected, Sweatt was denied entry to the law school because of his race, the NAACP took this case to the Supreme Court, too. In 1950, the Court ordered the university to let Sweatt enroll. This case set the precedent for the Court’s landmark 1954 Brown v. Board of Education ruling that ended school segregation in the United States. The court challenges White launched against discrimination made her a national civil rights figure. In 1949, she resigned as head of the Houston NAACP to become director of the state chapter. She held this position until her death in 1957. Describing What were the main contributions of Lulu Belle Madison White to the civil rights movement? Henry B. González (1916–2000) Henry B. González earned his reputation as a civil rights crusader long before he was elected to the first of his record 19 terms in the U.S. Congress. He was also known for hard work, independence, and a commitment to public service. “Henry B,” as González was widely known, was born in San Antonio, Texas. His immigrant parents had fled the Mexican Revolution in 1911. González attended San Antonio College and the University of Texas. In 1943, he earned a law degree from San Antonio’s St. Mary’s University. After working for military intelligence during World War II, González became a probation officer in Bexar County. e quickly rose to become Chief He quickly rose tp become Chief Progbation Officer.He quickly became chief probation officer. Soon, he made changes to address discrimination in the system. In 1953, González became the first Mexican American to serve on San Antonio’s city council. In that post, he worked to end the segregation of public facilities, such as city swimming pools. Elected to the Texas Senate in 1956, he was the first Mexican American state senator in more than 110 years. González soon gained national attention. He blocked the passage of bills aimed at getting around the Supreme Court’s school desegregation ruling in Brown v. Board of Education. In 1961, González was elected to Congress, making him the first Texas Mexican American to serve in the House of Representatives. There, he continued to fight for civil rights. González was one of only a handful of Texas representatives to vote for the landmark Civil Rights Act of 1964. During his 37 years in the House, González became an expert on the nation’s banking system and on housing for the poor. In 1981, he used his knowledge to bring about reforms that helped poor families get housing assistance. Later, he battled President Ronald Reagan’s efforts to cut public-housing programs. González’s commitment to the people of his district was unwavering. “This office belongs to the people of Bexar County,” read a sign outside his office door. At the same time, his independence and reluctance to compromise made him something of an outsider in Washington politics. “Accepted but . . . an inconvenient and unwelcome obstacle” is how González himself put it shortly before retiring in 1998. Yet he was an important figure in the Mexican American community. “Un abrecaminos,” one admirer described Henry B after his death—“Making the way for others.” Identifying How did González demonstrate good leadership in his efforts to improve civil rights? Hector P. García (1914–1996) Sometimes, students prove their teachers wrong. When Dr. Hector P. García was young, a teacher told him, “No Mexican will ever make an ‘A’ in my class.” As a doctor, soldier, and civil rights leader, García grew up wanting to prove that Mexican Americans were capable of anything. Born near Ciudad Victoria, Mexico, García moved with his family to the United States in 1917 to escape the Mexican Revolution. His parents were both educators and stressed the importance of education. So García studied hard; he was his high school’s valedictorian and then graduated with honors from the University of Texas. When he graduated from the University of Texas Medical School, he was the only Mexican American in his class. In World War II, García volunteered for the army and became a major. He eventually worked as a medical corps surgeon and was awarded the Bronze Star. During the war, he also met and married Wanda Fusillo from Naples, Italy. Back in Texas in 1948, García wanted to help improve conditions for other Mexican Americans. He founded the G.I. Forum, which now exists in 24 states. It became known nationwide when it publicized a clear case of discrimination against the family of a deceased veteran, Felix Longoria. In this case, a Texas funeral home would not allow Longoria’s widow to use its chapel for his wake. The funeral director admitted that this was because Longoria was Mexican American. García wrote to then-Senator Lyndon B. Johnson, who arranged for Longoria to be buried in Arlington National Cemetery. García formed the G.I. Forum to help Mexican American veterans get the benefits and medical care that they deserved. Over time, the organization took on many other civil rights issues for Mexican Americans. It worked to improve treatment for migrant workers, to desegregate schools, and to remove obstacles to voting. As García gained influence, even presidents asked for his service. President John F. Kennedy asked García to take part in talks for a defense treaty between the United States and the West Indies. President Lyndon B. Johnson appointed García to the United Nations and the United States Commission on Civil Rights. In 1984, Hector García was the first Mexican American to be awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom. He received many other awards and honors before his death in 1996. Today, a large statue of García honors him on the campus of Texas A&M University-Corpus Christi. Identifying How did Hector P. García contribute to progress in civil rights for Mexican Americans? Raymond L. Telles (1915–2013) Raymond L. Telles was an important Texan leader and political pioneer. He was the first Hispanic mayor of a major American city and the first Hispanic U.S. ambassador. He lived a long life dedicated to serving Texas and the United States. Born in El Paso in 1915, Telles attended local schools and what is now the University of Texas at El Paso. He joined the army and was decorated for his service in World War II. Telles also helped train Hispanic pilots in San Antonio, Texas. In 1948, Telles was encouraged by Hispanic veterans and others to run for county clerk. The veterans were tired of discrimination and wanted to gain some political power. Telles agreed to run, and he won the election. He held the office for several years. Then he returned to the army to serve in the Korean War. Telles achieved the rank of colonel and served as a military adviser to both Presidents Harry Truman and Dwight Eisenhower. By 1957, half the population of El Paso was Hispanic. However, this large group was barely represented in city politics. No Hispanic person had ever been mayor of El Paso or any other major American city. The Hispanic residents of the city wanted to be treated as full citizens, but this would happen only if they gained political power. Telles was persuaded to run for the office of mayor. On election day, a huge number of Hispanic voters came to the polls, and they made history. Telles was elected mayor and served for two terms. Hispanics in the United States now had a model of how to be successful in local politics. Telles was a friend of President John F. Kennedy. He also was one of his close advisers. In 1961, President Kennedy asked Telles to become ambassador to Costa Rica—the first Hispanic to serve in this position. In 1967, President Lyndon Johnson appointed Telles as the chairman of the U.S.-Mexico Border Commission. Telles also served on the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) under President Richard Nixon. Under President Jimmy Carter, he headed the Inter-American Development Bank in El Salvador. In 1982, Telles returned to El Paso. There, he became active in the private sector. He also helped bring the famous Kress art collection to the El Paso Art Museum. He died in California at the age of 97. Identifying What contributions did Raymond Telles make to the Hispanic community of El Paso? James L. Farmer, Jr . (1920–1999) Farmer was born in Marshall, Texas. His father was a college professor, and his mother was a former teacher. Farmer learned about racism at an early age. One day, while out with his mother, she said she could not buy him something he wanted at a particular store. Once home, his mother explained that African Americans were not allowed in that store. Farmer grew up ''determined to do something about'' this unequal treatment of African Americans. Farmer entered college when he was only 14 and earned two degrees, one in science and one in religion. He planned to become a minister in the Methodist Church, but he abandoned that idea because the church was segregated. In 1942, he and a white friend entered a coffee shop in Chicago. Although almost no one else was inside, the man running the shop made them wait. He then charged them a dollar for donuts that cost everyone else a nickel, told them to leave, and threw their money on the floor. This experience led Farmer to cofound the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE). Its purpose was to fight prejudice and segregation, and its first actions were sit-ins in Chicago restaurants. A sit-in was a form of protest in which protesters sat down and stayed where they were not allowed. Inspired by the nonviolent acts of Mahatma Gandhi, CORE volunteers began to protest segregation in Southern bus stations. Their efforts, begun in May 1961, became known as Freedom Rides. Although the protests often led to violence from segregationists, they also gained widespread support for the cause of civil rights. Farmer later said, ''In the end, it was a success because [U.S. Attorney General] Bobby Kennedy had the Interstate Commerce Commission issue an order...banning segregation in interstate travel. That was my proudest achievement.'' Farmer left CORE in 1966, taught at universities, and served as Assistant Secretary of Health, Education, and Welfare under Richard Nixon. In 1998, the year before his death, President Bill Clinton awarded Farmer the Presidential Medal of Freedom—our nation’s highest civilian honor—for his contributions to the civil rights movement. Describing What was CORE, and what were its goals and most famous achievement?