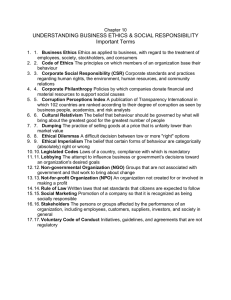

Case studies of staff assessments for monitoring integrity in the

advertisement