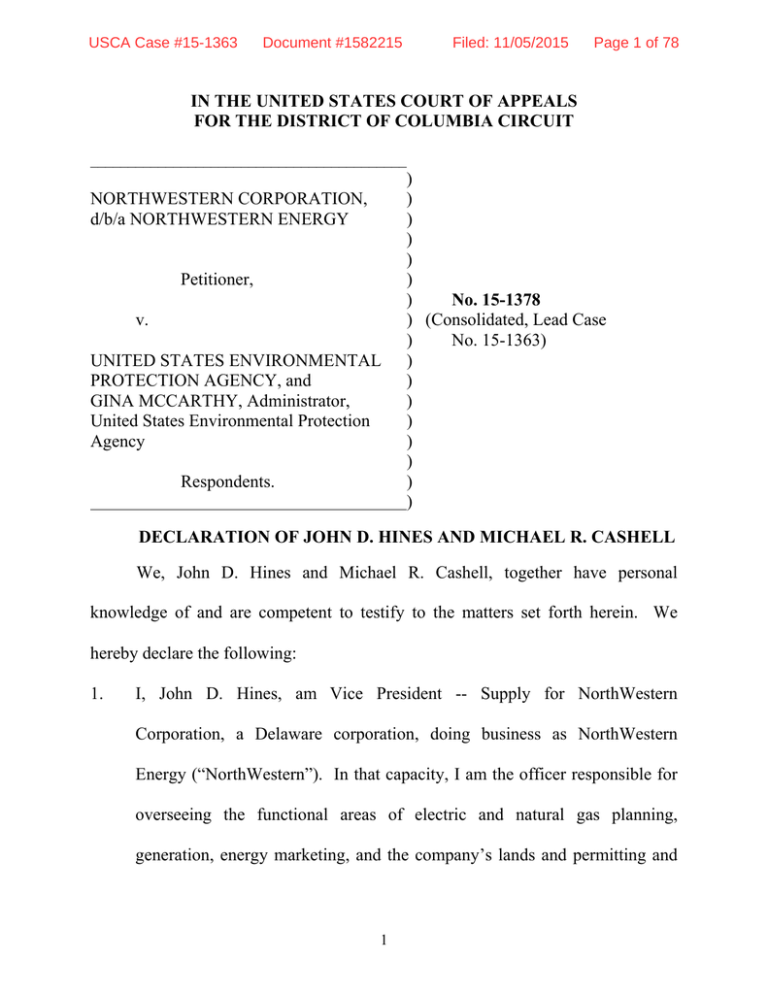

NorthWestern - Environmental Defense Fund

advertisement