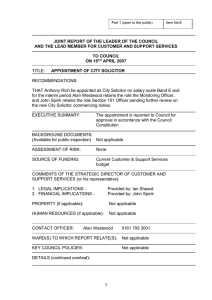

ETHICS AND CONFLICT OF INTEREST AND DUTIES

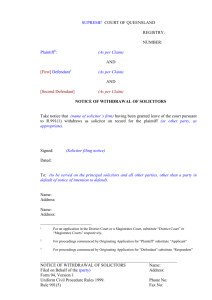

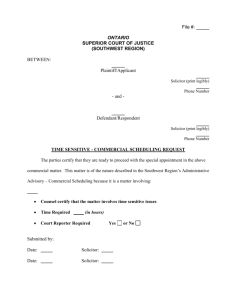

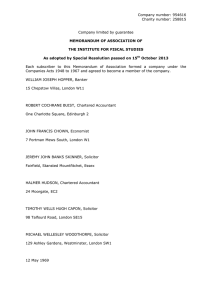

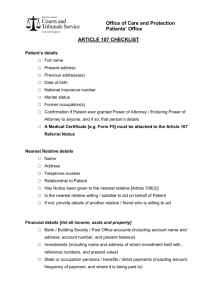

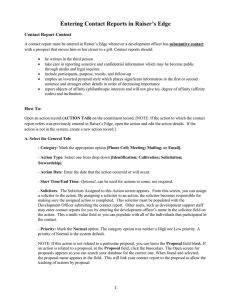

advertisement