Price Stability and Financial Stability: The Historical

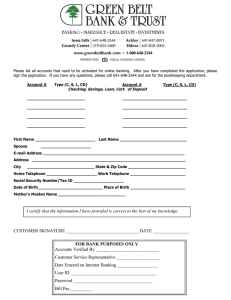

advertisement