Source - United States Court of Federal Claims

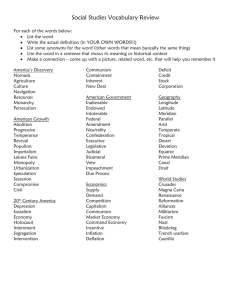

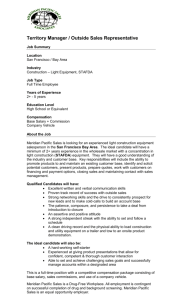

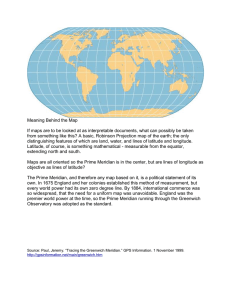

advertisement