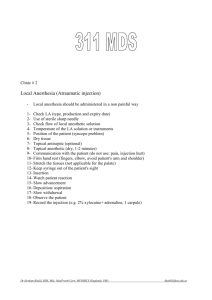

Guidelines for the use of local anesthesia in office-based

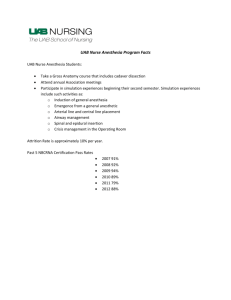

advertisement