Early Warning System for Financial Imbalances in Japan

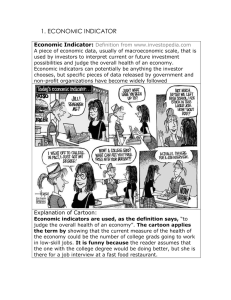

advertisement