Financial Reporting:

Pressure Mounts to Fix

the Close Process

TITLE 2

AUTHOR

Mary C. Driscoll

Senior Research Fellow

APQC

Introduction

APQC research shows that a growing number of CFOs and Controllers want to change a

key financial process that has operated in much the same way for decades. That

process, defined in end-to-end terms, is called either close-to-disclose or record-toreport. Whichever designation is used, the process involves all activities needed to close

an organization’s books, perform all necessary intra-company accounting and

reconciliation steps, finalize consolidated financial statements and, finally, release

earnings and publish official statements with regulators such as the Securities and

Exchange Commission (SEC).

They don’t have a choice—the close-to-disclose (C-to-D) process, particularly the final

stretch of financial statement preparation, is rife with inefficiency and complexity.

Previous gains made in cycle-time compression are gone. Risks of financial error and

internal control failures are on the rise. Experts in SEC reporting predict things will get

worse. No wonder the C-to-D process currently stands as the second-most desirable

target for improvement (Figure 1).

Most popular targets for financial process improvement in 2012

and 2013

78%

plan, budget, forecast/analyze, re-plan

72%

close/consolidate/report

70%

general accounting (any sub-process)

50%

AP transaction mgt. (any sub-process)

46%

working capital management

______________________________________________

Source: APQC survey on financial management process improvement, April 2012.

What’s behind this surge of interest? In an APQC webinar entitled “The Utopian Close”

that aired in February, 2013, Kyle Cheney, a partner with Deloitte & Touche LLP’s

Finance Transformation practice, gave four reasons for heightened concern over

instability in the C-to-D arena:

Page 2 of 10

Research provided by APQC, the international

resource for benchmarks and best practices

K04272

©2013 APQC. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

1) Business models have become more complex and the close process has not kept

pace.

2) Mergers have increased the number of organizations with disparate systems,

business models, and reporting.

3) Large companies have developed complex tax strategies that, coupled with

globalization, mean more statutory and regulatory requirements [at home and

abroad] for financial reporting.

4) Intense pressure and scrutiny by regulators has underscored the need to ensure

that these processes work properly. This has led to increased control

requirements layered on top of already complex processes.

Painful Problems

The consequences of ignoring potential C-to-D process failure can be substantial. The

most obvious is being cited by the SEC or other watchdogs for issuing financial

statements that contain mistakes. If material errors turn up in these statements, boards

of directors and senior executives will be widely criticized, heads will roll, fines will be

levied, and corporate reputations will suffer blows that may take years to repair.

Beyond that, according to Mr. Cheney, a compliance failure can easily lead to a multimillion-dollar problem.

For some organizations, the worry over error in financial reporting relates to the

number of entities that have to be consolidated and the number of secondary systems

that have to be tapped—e.g., treasury, tax, and fixed assets, and non-financial

databases such as those used in sales and marketing.1 All manner of havoc could break

lose. There could be system interface failures; or there could be inconsistency in the

updating of supporting documents (somebody updates the consolidated number but

fails to go back and update the sub-ledgers). Beyond that, say experts who have either

managed the close process or have helped companies make repairs, some entities that

have spent vast sums on ERP technology (to automate transactions) but still ask their

finance staffs to perform manual data entry involving multiple spreadsheets. That in

itself is a recipe for trouble.

Gabe Zubizarreta, the CEO of Silicon Valley Accountants, is a seasoned close veteran. He

has served as a financial executive and has been in the thick of things during the close

cycle. Today he consults and teaches courses in this realm. “Chances are, you carry

1

Mary Driscoll. “Fortifying the Close-to-Disclose Process.” APQC Knowledge Base, October, 2012.

Page 3 of 10

Research provided by APQC, the international

resource for benchmarks and best practices

K04272

©2013 APQC. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

better technology in your cell phone than you have for managing your close. And when

you’re relying on spreadsheets, you’re one slip away from something very bad

happening. For instance, one company slipped up badly when they booked a tax

number and somebody forgot the parenthesis. They wound up booking the number

backwards: the statements were about to go out with a $9 million tax debit on the

expense line instead of a credit. And because an excel spreadsheet was used to add the

number, everything appeared to be just fine. The auditors caught the mistake at the last

minute, but if not, there would have been a potential issue.”

Beyond the potential for compliance failure, there is the burden carried by people

working on the close. They can easily get burned out from having to spend late nights

and weekends toiling away under extreme pressure. The books have to close, and

performance results have to be released no matter what. And the people involved

usually do whatever it takes to get the job done. But the last thing a CFO wants is high

staff turnover when it comes to the close. The finance staffers involved tend to be welltrained in managerial accounting as it applies to a given company’s operating model and

global footprint—losing them can result in a big knowledge gap that can take months to

close.

Another problem that comes from tolerating a weak process design and lousy tools is

the amount of time wasted on what feels like grunt work. Finance executives often

complain that they have to spend an inordinate amount of time assembling, reconciling,

and consolidating data, and then there’s precious little time left at the end of the

process for critical review. They desperately want more time to think through what the

financial results say about the underlying drivers of business performance. They want to

prepare meaningful analyses for senior executives, board members, and external

stakeholders. But that work often takes place at the 11 th hour. Inevitably, the quality of

the analytical output suffers.

A Better Way

A company can achieve what Mr. Cheney calls “the Utopian Close,” which not only

demolishes the root causes of error in financial statements but also delivers efficiency

gains in the neighborhood of 25 percent. He argues that a CFO can come out the other

side of a close-process overhaul attesting to the following:

“My team is motivated. They put their talent to best use.”

“I know the precise status of the close at any point along the way.”

Page 4 of 10

Research provided by APQC, the international

resource for benchmarks and best practices

K04272

©2013 APQC. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

“I have clear visibility into the numbers in all my divisions and geographies.”

“Our MD&A2 gives an insightful view of our business. I can clearly articulate

variances to plan and the prior year.”

“Before I hit the button and send documents to the SEC, I know exactly what has

been reconciled.”

“We have a lean and short close.”

Big Potential for Cost Savings

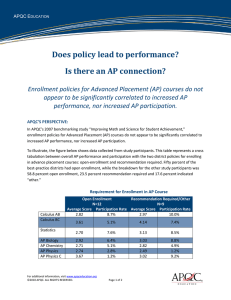

Interestingly, a look at costs shows that if steps are taken to make the C-to-D process

less labor-intensive, a company can capture significant savings. Figure 1 draws from the

APQC’s Open Standards Benchmarking database. For this view, APQC gathered the

performance of 148 U.S. organizations with annual revenue greater than $1 billion that

took the survey on financial reporting and answered the question about process cost.

The results were then sorted into quartiles. The top quartile is the performance level

above which 25 percent of all responses occur. The bottom quartile is the performance

level above which 75 percent of all responses occur. The median is the middle value in a

set of values that are arranged in ascending or descending order.

The data shows that the bottom performers spend five times more on the process than

the top performers. Surely, this comes as no big surprise. CFOs have known all along

that they could capture good amounts of savings if they were willing to invest in process

redesign and automation. But until now, the ROI just didn't seem to outweigh the hassle

factor. What has turned things around is that the cost picture, juxtaposed with the

heightened risk of process failure and the need for faster cycle times, points to a clear

rationale for change.

2

Management discussion and analysis: A section of a company's annual report in which management discusses numerous aspects of

the company and its performance, both past and present. Management will usually also touch on the upcoming year, outlining

future goals and approaches to new projects. Source: Investopedia.

Page 5 of 10

Research provided by APQC, the international

resource for benchmarks and best practices

K04272

©2013 APQC. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

Total Cost of Financial Reporting per $1,000 in Revenue

$0.60

$0.57

$0.50

$0.40

$0.30

$0.23

$0.20

$0.11

$0.10

$0.00

Top Performers

Median

Bottom Performers

All Industries, Revenue greater than $1 Billion

N = 148

10 Commandments for Effective Change

How to approach the challenge of improving the close? For a set of practical

recommendations, APQC turned to David Taylor, an Associate Chartered Management

Accountant and an International Associate of the AICPA3. He serves on Financial

Executives International’s Committee on Finance and IT and on a Research Advisory

Panel run by CIMA.4 Mr. Taylor is currently Trintech’s Executive Vice President. Here are

his “10 Commandments.”

Note: he prefers the phrase record-to-report (R-to-R) over close-to-disclose (C-to-D).

Commandment 1: Start with the end in mind. At the end of the day, R-to-R is about

accurate and timely financial information made available to stakeholders. Similar to any

process improvement, always assess change to the process in light of the overall health

3

American Institute of Certified Public Accountants.

4

Chartered Institute of Management Accountants.

Page 6 of 10

Research provided by APQC, the international

resource for benchmarks and best practices

K04272

©2013 APQC. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

of the process. Ask: what are the most important parts of the R-to-R process? If you

address one bottleneck, what is the knock-on effect upstream and downstream to the

entire system? Are the biggest bottlenecks being addressed in terms of duration,

resources, and risk?

Commandment 2: Ensure you are spending adequate time on the key activities. Key

activities in the R-to-R process are typically defined by risk and quality. The primary risk

is that the output (e.g., financial information for various stakeholders) may be

incomplete, inaccurate or untimely. Major activities determining the risk and quality of

output are: ensuring accuracy in reconciliations, ensuring proper review/approval of all

activities by responsible parties, and ensuring compliance with organizational policies.

Always keep accurate back-up and audit documentation. Ensure that you have deep

visibility and sound governance throughout the process for assurance purposes.

Commandment 3: R-to-R is an overhead item, so minimize the cost with gusto but not

to the detriment of quality or risk management. Closing the books and producing

disclosures in and of itself does not lead to an increase in corporate revenue or asset

value. Therefore, this activity needs to be minimized in terms of duration and maximized

in terms of efficiency. Keep in mind, however, there are key value-add activities

surrounding the close. Strategic planning is an example, and the planners are highly

dependent on quality output from the R-to-R process. Do not sacrifice absolute quality

for the sake of efficiency.

Commandment 4: Align the appropriate skills to the appropriate activities. One of the

major issues with R-to-R is utilizing highly skilled professional accountants to perform

routine tasks. If the task can be standardized and is routine, don’t insult your highly

trained accountants. Instead, have the work performed by lower cost personnel, and if

possible use a shared service center. The outcome: higher levels of morale and

significant savings.

Commandment 5: Time is everything. Timeliness in the R-to-R process is critical. At the

end of the process, stakeholders are eager for the information so they can perform their

own evaluations of the organization and its performance. Improving cycle times must be

a key goal—and it helps to understand the root causes of slower-than-desired cycles.

Commandment 6: Be relentless in automation. Process automation that involves

suitable technology provides the opportunity to eliminate redundant tasks and perform

Page 7 of 10

Research provided by APQC, the international

resource for benchmarks and best practices

K04272

©2013 APQC. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

routine tasks without human intervention. By automating as much as you possibly can,

you will save significant time and money.

Commandment 7: Be relentless in standardization. When considering standardization,

look outside your four walls. By networking with peers, you will find new ideas for

standardization across the entire process. For example, creating standardized templates

for reconciliations, journal entries, and financial disclosures will move you more quickly

into the stage in which reviews and approvals take place.

Commandment 8: Be in a constant state of communication. Communicating

continuously on the progress of the R-to-R cycle will reduce distractions to those further

downstream in the process. Openly communicating the current state of the cycle will

help everyone understand when it’s their turn to participate and to what extent, and

that includes the CEO and CFO.

Commandment 9: Benchmark, Benchmark, Benchmark. Measuring the process of R-toR is critical. Determine the most effective measures for your process and check on them

during each cycle. Measuring performance and quality only leads to continuous

improvement. Where possible, benchmark these measures with other organizations of

similar size and structure.

Commandment 10: Plan on change—it will happen. Be in a position of adapting to

change. Business has become dynamic for all organizations, therefore it is critical to

operate in a state of readiness for activities like mergers and acquisitions, financial crisis,

geographical expansion and last, but certainly not least, expanding regulatory

requirements in all jurisdictions.

A Final Word

Gabe Zubizarreta puts the need for change in sharp relief: “Getting your close 96

percent right is not an “A” or an “A+”. Rather, 96 percent is an “F”. And even if you get

everything right, an auditor can come along and say, ‘I know you got the right answer,

but I think you didn’t have the necessary controls. Maybe you wouldn’t have recognized

the wrong answer, and therefore without better controls, we’re going to give you a

material weakness.’ Now, you’ve got a potential issue with the auditors,” he says.

Surely, the quality standards involving the close are incredibly high. The tolerance for

weakness is extremely low. And the scrutiny is intense. But there are sound

technologies on the market today that can make a major difference. And there are

Page 8 of 10

Research provided by APQC, the international

resource for benchmarks and best practices

K04272

©2013 APQC. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

numerous approaches to change. Some companies aim first for quick wins, such as

establishing a consistent close calendar or bringing the activities surrounding XBRL

publishing in-house. They then work their way up to initiatives such as automating and

improving the enterprise-wide account reconciliation process or simplifying

intercompany and transfer pricing transactions and policies.

Finally, finance organizations that commit to continuous improvement in the

management of the close-to-disclose process tend to find themselves pursuing

milestones that promise benefits for decision-makers beyond the walls of finance. It’s a

journey toward supreme confidence in the performance management machinery—and

that enables cohesion in planning and plan execution.

ABOUT APQC

APQC is a member-based nonprofit and one of the leading proponents of benchmarking and

best practice business research. Working with more than 500 organizations worldwide in all

industries, APQC focuses on providing organizations with the information they need to work

smarter, faster, and with confidence. Every day we uncover the processes and practices that

push organizations from good to great. Visit us at www.apqc.org and learn how you can make

best practices your practices.

Copyright ©2012 APQC, 123 North Post Oak Lane, Third Floor, Houston, Texas 77024‐7797 USA

All terms such as company and product names appearing in this work may be trademarks or registered trademarks of

their respective owners. This report cannot by reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic or

mechanical, including photocopying, faxing, recording, or information storage and retrieval.

Page 9 of 10

Research provided by APQC, the international

resource for benchmarks and best practices

K04272

©2013 APQC. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

Page 10 of 10

Research provided by APQC, the international

resource for benchmarks and best practices

K04272

©2013 APQC. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED