Food Safety Knowledge and Practices among Women Working in

advertisement

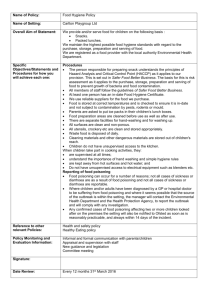

J Egypt Public Health Assoc Vol. 84 No. 1 & 2, 2009 Food Safety Knowledge and Practices among Women Working in Alexandria University, Egypt Mohamed Fawzi*, Mona E. Shama** * Department of Nutrition, High Institute of Public Health, Alexandria University ** Department of Health Administration and Behavioral Sciences, High Institute of Public Health, Alexandria University ABSTRACT Ensuring food safety at the household level is well accepted and an understanding of the status of the food handling knowledge and practices is needed. Food safety knowledge and practices of 270 women working in six faculties and institutions of Alexandria University were assessed using a questionnaire including data on personal characteristics, previous attack of prominent food poisoning, and four parameters of food safety knowledge and practices. The highest percentage of food poisoning cases (46.8%) was belonging to staff members and 39.7% were in the age group <10 years. Half of the cases resulted from eating outside home compared to 16.7% from eating at home. The mean score percentage of the total safety Knowledge of the sample was 67.4 compared to 72.0 for their safety practices. The highest Knowledge score was in personal hygiene (73.8) while the highest practice score was in cooking (77.5). The lowest Knowledge score was in food preparation (59.8) whereas the lowest practice was in purchasing and storage (62.7). The highest mean scores percentages of the total food safety knowledge and its four associated parameters were among staff members with significant differences among different jobs except in food preparation. The highest scores of the total food safety practices and their parameters were among clerks except in practicing safe purchasing and storage where the highest mean score was among staff Corresponding Author: Dr. Mohamed Fawzi Department of Nutrition, High Institute of Public Health, Alexandria University e.mail: mohamedfawzi_hiph@yahoo.com J Egypt Public Health Assoc Vol. 84 No. 1 & 2, 2009 members (66.5± 12.8) with significant differences among jobs except in practicing personal hygiene. Conclusion and recommendations: The study showed inadequate safety Knowledge and practices among all job categories. The inconsistencies between Knowledge and practices emphasize the need for implementing repeated food safety education programs. Key words: Food safety knowledge, food safety practices, food poisoning, personal hygiene. INTRODUCTION The incidence of foodborne diseases is rising in developing countries, as well as in the developed world.(1) Although their global incidence is difficult to estimate, it has been reported that in 2000 alone 2.1 million people died of diarrheal diseases. A great proportion of these cases contamination of food and drinking can be water.(2) attributed to Food prepared at home has been identified as a major source of food poisoning.(3) In response to the increasing number of foodborne illnesses, governments all over the world are intensifying their efforts to improve food safety.(2) Food safety is defined as the degree of confidence that food will not cause harm to the consumer when it is prepared, served and eaten according to its intended use.(4) Although the public is increasingly concerned about foodrelated risks, the rise in food poisoning cases suggests that people still make decisions of food consumption that are less ideal from the safety perspective.(5) The percentage of food poisoning cases arising from food preparation practices at home may be especially under-represented in outbreak statistics.(6) Common mistakes identified include serving contaminated raw food, cooking/heating food inadequately, having infected persons handle implicated food and practice poor hygiene.(7) Two studies 96 J Egypt Public Health Assoc Vol. 84 No. 1 & 2, 2009 conducted at the Alexandria Poison Center reported that home was the place of eating the incriminated food in 60.7% and 85% of the microbial food poisoning cases admitted during 1995 and 1998; respectively.(8,9) The role of food handlers, usually mothers, in ensuring food safety at the household level is well accepted and an understanding of the status of their food handling knowledge and practices is needed.(10) A study in Turkey (2007), reported that consumers have inadequate knowledge about measures needed to prevent foodborne illness in the home.(11) Given that it is currently impossible for food producers to ensure a pathogenfree food supply, home food preparers need to take many precautions to minimize pathogenic contamination because they are the final line of defense against foodborne illnesses.(10) There are no regulations for the preparation, handling, and storage of food at home.(11) An effective risk communication to inform consumers of the possible health risks of foodborne diseases and encourage safer food handling practices at home is probably the best way to ensure food safety at the consumer end of the food chain.(12) Obtaining enough information on the knowledge and practices of a target group is essential for the development of effective health education programs. The aim of this study was to assess food safety knowledge and practices among women working in Alexandria University. MATERIAL AND METHODS The present cross sectional study was conducted on 270 females working in Alexandria University and having the responsibility of food preparation at their homes. They were recruited from six faculties and institutions affiliated to Alexandria university namely; High Institute of Public Health and 97 J Egypt Public Health Assoc Vol. 84 No. 1 & 2, 2009 Medical Research Institute in addition to the Faculties of Pharmacy, Sports, Education, and Science. Faculties and institutions were chosen according to personal communication with a staff member who could facilitate data collection. Data was collected through distributing 45 questionnaires in each faculty/institution (15 for each of staff, clerks and workers). The questionnaire included the following four sections: personal characteristics (educational level, number and age of their family members), previous attack of a prominent food poisoning (its cause, number of victims and their age), food safety knowledge (32 questions) and food safety practices (35 questions). A prominent food poisoning was that associated with severe vomiting and/or hospitalization of the victim. Questions in each section of the food safety knowledge and practices were included under four main parameters; food purchasing and storage, preparation, cooking and personal hygiene The questionnaire was pilot tested on 20 women and amended for clarity with the addition of some answer options. Although the questionnaire was intended to be self administered, some illiterate workers needed help in filling it. All questions were of the multiple choice type. Each knowledge question has only one right answer and scored by giving one for the right answer and zero for the wrong as well as to “don’t know” answer. Questions related to food safety practices included a set of positive and negative sentences. Thirty three practice questions had 3 responses and scored from 0 to 2 while the remaining two questions had four responses and scored from 0 to 3 with higher scores for better practices. The score of each parameter was calculated by summing the scores of its questions and the total score of the whole food safety knowledge and practice was calculated by 98 J Egypt Public Health Assoc Vol. 84 No. 1 & 2, 2009 summing the scores of its four parameters. All knowledge and practice scores were transformed into percentages. Croncbach alpha coefficient of internal consistency was used to estimate the reliability of the questionnaire. Alpha coefficient was 0.798. Statistical Analysis Data was statistically analyzed using SPSS program version 14.0. The cutoff point for statistical significance was P value < 0.05 and all tests were two-sided. Data was tabulated and presented in the form of arithmetic mean and standard deviation for score percentage of the total food safety knowledge and practices and their parameters. As some parameters were not normally distributed, non parametric tests (Kruskal-Wallis and Mann Whitney) were used as tests of significance. Kruskal-Wallis test was used to compare score percentages of knowledge and practices among different jobs and Mann Whitney test was used to test the relation between knowledge and practice score percentages, and food poisoning. Because many of the cross-tabulations had cells with expected count less than 5, Monte Carlo proportion was used to compare the percentages of food poisoning cases as well as right answers among different jobs.(13) RESULTS A total sample of 270 female women working in Alexandria University (90 of each of staff members, clerks and workers) participated in this study. Their average age was 42.5 ± 10.6 years, with one third of them in the age group 40-<50 years. They served 910 family members about half of them (50.2%) were in the age 99 J Egypt Public Health Assoc Vol. 84 No. 1 & 2, 2009 group 10-29 years and 17.6% were with less than 10 years. They reported 126 cases of food poisoning. The highest percentage of cases was belonging to staff (46.8%) while the lowest (23%) was belonging to clerks, with statistically significant differences among different jobs. The highest percentage of food poisoning cases was in the age group <10 years (39.7%). Half of the cases occurred as a result of eating outside home, while 16.7% occurred as a result of eating at home. Table (1) shows food safety knowledge and practices related to food purchasing and storage among women working in Alexandria University. The percentages of the right knowledge ranged from 25.6% in “food poisoning microorganisms can't be destroyed in the freezers" to 90.7% in the question "growth of food poisoning microorganisms is faster at room temperature than in refrigerator". The highest percentages of the right practices was in "firstly purchased foods are consumed first" (88.5%), followed by "reading expiry date before purchasing" (77%), while the lowest were in purchasing iced fish and not purchasing farmers' kariesh cheese (27.8% and 29.3%; respectively). There were significant differences among different jobs regarding practicing safe purchasing and storage except in purchasing iced fresh fish and avoiding storage of cooked food hot in chillers. 100 J Egypt Public Health Assoc Vol. 84 No. 1 & 2, 2009 101 J Egypt Public Health Assoc Vol. 84 No. 1 & 2, 2009 The results of the food safety knowledge and practices related to food preparation are shown in table (2). The percentages of the right knowledge ranged from 43% in recognizing thawing frozen foods at room temperature as a possible cause of food poisoning to 68.1% in linking the use of the same cutting boards between raw and cooked food, and food poisoning. Differences among different jobs were significant only in appreciating that thawing frozen food at room temperature can cause food poisoning; with staff members showing the highest percentage of right answers (51.1%). The majority of the sample used not to refreeze the thawed frozen foods (87%) and to use separate or properly cleaned cutting boards between raw and cooked foods (81.5%). On the other hand, only 4.4% were usually soaking salad vegetables in water with potassium permanganate and 10.4% were thawing food during cooking. The percentages of correct practices differed significantly among different job categories in “washing salad vegetables" and "using separate or properly cleaned cutting boards between raw and cooked food" with clerks showing the highest percentages. Table (3) illustrates food safety knowledge and practices related to food cooking. The majority of the studied women mentioned that inadequately boiled milk can cause food poisoning (85.2%) and it is safer to cook for one day (81.5%). On the other hand, about half of them recognized raw or half cooked food of animal origin, and inadequately reheated cooked food as causes of food poisoning (54.4 and 53.3% respectively). Significant differences were found across job categories except in questions of "it is safer to cook food quantities sufficient for one day" and " prepared food should not kept for >4 hrs outside the chillers". Regarding safe cooking practices, the highest percentages were in storing cooked and leftover food 102 J Egypt Public Health Assoc Vol. 84 No. 1 & 2, 2009 103 J Egypt Public Health Assoc Vol. 84 No. 1 & 2, 2009 104 J Egypt Public Health Assoc Vol. 84 No. 1 & 2, 2009 in the chillers for ≤ 3days (95.6%) followed by adequate reheating of liquid food (90.4%) and reheating of a portion sufficient for a meal (81.9%). The lowest percentages were in checking adequacy of food cooking by examining internal and external color changes (11.5%) followed by adequate reheating of solid food (33.7%). Table (4) shows that all women recognized the importance of proper hand washing for preparing safe food, and the majority mentioned that hands should be free of wounds (94.4%), with short and clean nails (95.6%), and cooked food should not be tasted by fingers or placing unclean spoons (81.9%); while the lowest (33.7%), appreciated the role of apparently health persons as a source of food contamination. Significantly higher percentage of staff members recognized that diseased persons and apparently healthy persons are sources of food contamination with food poisoning microorganisms. Concerning practicing personal hygiene, all women used to wash their hands after visiting the toilet and 88.5% used to wash hands before food preparation though only 20% used to wash with warm water and soap. The used method of hand drying, and washing of faucets’ handles differed significantly among jobs. The highest mean score percentages of the total food safety knowledge and its four associated parameters were among staff members with significant differences among different jobs except in food preparation. On the other hand, the highest score percentages of the parameters were total food among clerks safety practices and their except in practicing safe purchasing and storage where the highest percentage was among staff members (66.5± 12.8) with significant differences among jobs except in practicing personal hygiene (Table 5). 105 J Egypt Public Health Assoc Vol. 84 No. 1 & 2, 2009 106 J Egypt Public Health Assoc Vol. 84 No. 1 & 2, 2009 Table (5): Food Safety Knowledge and Practices among Women Working in Alexandria University Food safety Knowledge Practices Staff Clerks Workers Total Mean±SD Mean±SD Mean±SD Mean±SD Purchasing and storage 69.8±15.8 66.3±13.1 57.1±15.4 64.4±15.7 37.308* Preparation 66.1±33.2 58.1±33.7 55.3±35.8 59.8±34.4 4.791 Cooking 76.0±24.6 70.2±24.8 63.8±24.9 70.0±25.2 11.992* Personal hygiene 79.8±16.5 72.5±16.5 69.3±16.4 73.8±17.0 19.703* Total 73.1±14.8 67.6±12.6 61.3±14.7 67.4±14.8 31.060* Purchasing and storage 66.5±12.8 63.1±15.0 58.6±15.4 62.7±14.7 13.747* Preparation 70.7±13.9 72.0±13.2 64.2±14.6 69.0±14.3 13.004* Cooking 78.7±11.8 79.9±12.3 73.9±13.6 77.5±12.8 10.866* Personal hygiene 70.8±11.0 73.0±11.2 69.9±14.0 71.3±12.2 3.088 Total 73.3±7.6 74.0±8.8 68.5±9.9 72.0±9.1 20.125* Parameters KW# # Kruskal Wallis test among different jobs *p<0.05 Table (6) shows food safety knowledge and practices of women in relation to food poisoning. The mean score percentages of the total food safety knowledge and practices among women reporting no food poisoning were higher than those reporting food poisoning except in case of staff members where similar scores (73.1) were found. Differences in the total mean score percentage of food safety knowledge or practices of different jobs in relation to food poisoning were all insignificant except in workers’ knowledge. 107 J Egypt Public Health Assoc Vol. 84 No. 1 & 2, 2009 Table (6): Food Safety Knowledge and Practices of the studied Women in Relation to Food Poisoning Food safety Job Staff Clerks Knowledge Workers Total Staff Clerks Practices Workers Total Occurrence of food Purchasing poisoning & storage Yes (n= 31 ) 69.4±16.2 No (n=59 ) 70.1±15.7 MW 0.751 Yes (n= 17 ) 60.5±17.7 No (n=73 ) 67.7±11.5 MW 0.076 Yes (n= 24 ) 51.2±16.8 No (n=66 ) 59.2±14.4 MW 0.018* Yes (n= 72 ) 61.2±18.3 No (n=198 ) 65.6±14.5 MW 0.042* Yes 67.0±10.9 No 66.2±13.8 MW 0.934 Yes 62.3±13.9 No 63.2±15.3 MW 0.619 Yes 59.0±16.8 No 58.5±14.9 MW 0.739 Yes 63.2±14.0 No 62.5±15.0 MW 0.972 MN: Mann Whitney test ±SD) Parameters (Mean± Personal Cooking hygiene 64.5±35.2 78.1±25.0 80.0±18.5 67.0±32.3 74.9±24.5 79.7±15.6 0.826 0.481 0.696 57.4±36.2 71.8±18.8 69.9±19.5 58.2±33.3 69.9±26.1 73.1±15.8 0.962 0.996 0.563 35.4±32.1 55.0±26.5 59.7±16.6 62.5±34.6 67.0±23.7 72.7±15.0 0.001* 0.061 0.002* 53.1±36.3 68.9±26.0 70.8±20.0 62.2±33.5 70.4±24.9 74.9±15.7 0.067 0.753 0.171 71.0±12.2 76.5±12.5 70.8±11.2 70.5±14.9 79.9±11.4 70.9±11.0 0.901 0.209 0.938 71.4±13.9 80.6±12.5 70.6±11.6 72.1±13.1 79.7±12.3 73.5±11.1 0.875 0.736 0.240 65.8±13.7 69.3±14.9 63.0±14.0 63.6±14.9 75.6±12.9 72.4±13.2 0.778 0.061 0.002* 69.4±13.2 75.0±13.9 68.1±12.7 68.8±14.7 78.4±12.3 72.4±11.8 0.924 0.083 0.007* Preparation Total 73.1 ± 16.7 73.1±13.8 0.595 64.5 ± 17.3 68.4±11.2 0.411 52.2 ± 15.8 64.6±12.9 0.000* 64.1 ± 18.7 68.5±13.0 0.124 72.5 ± 6.9 73.8±8.0 0.449 73.5 ± 6.8 74.1±9.2 0.714 65.5 ± 11.4 69.6±9.2 0.159 70.4 ± 9.2 72.5±9.1 0.158 *p<0.05 DISCUSSION Consumers play a crucial role in prevention and control of food-related diseases, since all hygiene measures involved in food production, storage and distribution can be negated by poor food handling practices.(14) The present study revealed that workers had the lowest levels of both food safety knowledge and practices. Staff members had the highest levels of knowledge whereas clerks had the highest levels of practices in all 108 J Egypt Public Health Assoc Vol. 84 No. 1 & 2, 2009 parameters except in purchasing and storage. Socioeconomic class and educational level can affect food safety knowledge and awareness, with lower levels of knowledge related to lower educational levels and lower socioeconomic classes.(15) Food safety Knowledge and practice scores varied across the four parameters. The highest Knowledge score was in personal hygiene (73.8) while the highest practice score was in cooking (77.5). The lowest Knowledge score was in food preparation (59.8) whereas the lowest practice was in purchasing and storage (62.7) (table 5). This finding can guide health education programs to give more attention to improve knowledge defects related to the parameters with the lowest knowledge scores. The results also show that the mean score percentages of food safety practices in two food safety parameters; preparation and cooking (69.0 and 77.5; respectively) were higher than their corresponding knowledge (59.8 and 70.0). This indicates that some women used to do the right practices although their knowledge was deficient. The explanation is that women may be taught the right preparation and cooking practices from their mothers or other relatives without having the correct knowledge. On the other hand, the Knowledge score percentage in the other two parameters; purchasing and storage, and personal hygiene (64.4 and 73.8; respectively) were higher than their corresponding practices (62.7 and 71.3). This indicates that some women may have the correct knowledge but failed to do the correct practices probably due to lack of facilities as in case of lack of warm water for proper hand washing, or lack of other alternatives as in case preparing the food while ill and purchasing non refrigerated food of animal origin. Another study reported that the vast majority of consumers (95%) were engaged 109 J Egypt Public Health Assoc Vol. 84 No. 1 & 2, 2009 in less than ideal hygiene practices due to lack of knowledge or failure to implement known food safety procedures.(16) Food poisoning among families of the studied women: Although everyone is susceptible to food poisoning, infants and young children, pregnant women, the immunocompromised, and the elderly are more likely to experience severe consequences.(17) The present study revealed that 17.6% of the 910 served family members were in the vulnerable age group less than 10 years. A total of 126 food poisoning cases occurred among women and their family members (n=1180) comprising 10.7% with the highest proportion of cases (39.7%) in the age group less than 10 years. Other studies reported that this age group was the highest admitted to Alexandria Poison Center from 1990-1994 (1748 cases representing 26.1%) and from August 1997 till July 1998 (166 cases; 36.7%).(8,9) Unexpectedly, about half of the reported food poisoning cases (46.8%) were belonging to staff members, though they represent the highest social and educational level of the three job categories and they had the best mean food safety knowledge scores. The most reasonable explanation that could be given to this finding is that eating outside home was the main cause of food poisoning among this group. Any one is liable to be a victim of food poisoning, since most causative microorganisms do not alter food sensory properties i.e. its taste, odor, color...etc.(18) It is worth mentioning that all women mentioned that they suffered several episodes of mild food poisoning. Outside home was the place of eating the incriminated food reported by half the women while only 16.7% were in home. However, in a review of the consumer's food safety KAP (2004) it was found that many consumers were unaware that at least 60% 110 J Egypt Public Health Assoc Vol. 84 No. 1 & 2, 2009 of food poisoning originates in the home believing that the responsibility lies instead with restaurants and food manufactures.(19) Food safety knowledge among women (n=72) to whom food poisoning cases (n= 126) were belonging was slightly lower than the other 198 women with significant difference in the purchasing and storage parameter. Also they reported worse food safety practices in cooking and personal hygiene that were significant in personal hygiene indicating its importance in prevention of food poisoning. Knowledge and practices related to food purchasing and storage: Concerning purchasing and storage, the knowledge score percentage of the total sample (64.4) was slightly higher than the corresponding practice score (62.7) with significant difference among different jobs. This can be attributed to observed variations between their knowledge and practices regarding purchasing of unrefrigerated raw or frozen food of animal origin and purchasing iced fresh fish. Most of the sample recognized that displaying raw food unrefrigerated can contribute to food poisoning (77.4%), though only 58.1% used to purchase refrigerated food. Also, most of them (72.6%) mentioned that fresh fish not stored in ice is risky, though only 27.8% used to purchase the iced fish. This can be attributed to a common belief that fish sellers usually put ice on fish remained unsold from the previous day and the addition of ice means they are stale. Knowledge and practices related to food preparation: The mean score percentage of safe preparation practices was higher among women than their knowledge score (69 and 59.8; 111 J Egypt Public Health Assoc Vol. 84 No. 1 & 2, 2009 respectively) with significant differences among different jobs in their practices. This can be attributed to noticeable differences between their knowledge and practices concerning thawing of frozen food, refreezing of thawed frozen food and using of cutting boards. For example, the majority of women (87%) used not to refreeze the thawed frozen food but properly cook them to be used in another day, yet only 63.7% recognized thawing and refreezing as a cause of food poisoning. Food should never be thawed or stored on the counter, since food poisoning microorganisms grow faster in the middle of the temperature danger zone (21–52°C) than at any other point.(20) Safe thawing was practiced by 40% of the studied women where 29.6% used to thaw in the chiller and 10.4% used to thaw during cooking while the other 60% were thawing either at the kitchen temperature, by soaking in water or under running water. Only 43.0% of the sample mentioned that thawing frozen food at room temperature can cause food poisoning. A study in Trinidad (2006) reported that the practices of thawing frozen foods varied significantly among the respondents. They were thawing on the counter (41.6%), in cold water (28.0%), in microwave oven (18.4%) and in the refrigerator (12.0%).(20) The use of the same cutting boards for raw and cooked food of animal and vegetable origin without thorough proper washing can be one of the causes of food poisoning.(21) Though 81.5% of the studied women reported using separate or the same properly cleaned cutting boards between raw and cooked food of animal origin, only 68.1% recognized that failure to do this practice can lead to food poisoning. 112 J Egypt Public Health Assoc Vol. 84 No. 1 & 2, 2009 Knowledge and practices related to food cooking: Despite Americans have become more food safety–conscious during the past decade, they frequently engaged in risky eating behaviors e.g. eating raw or undercooked food of animal origin.(22) The mean score percentage of food cooking practices was higher (77.5%) among the studied women than their knowledge (70%). This may be attributed to discrepancies between their knowledge and practices concerning reheating of cooked food and boiling of raw milk. The majority of the studied women (90.4%) used to adequately reheat liquid food e.g. soup while only 33.7% reported adequate reheating of solid food e.g. rice and macaroni. The link between consumption of inadequately reheated food and food poisoning was appreciated by 53.3% of the sample. Although 75.6% of the sample mentioned that cooked food should not be kept outside chillers for more than 4 hours, only 58.9% used not to leave their cooked food for longer periods in the kitchen. Leaving cooked food for longer periods in the kitchen constitutes a hazardous practice since food poisoning microorganisms can grow to produce large number and/or toxins sufficient to induce food poisoning. Keeping leftover food for several hours at the kitchen temperature with inadequate reheating was the highest contributing factor in microbial food poisoning outbreaks admitted to Alexandria Poison Center from August 1997 till July 1998 (36.6%).(9) Although the role of inadequately boiled milk in causing food poisoning was mentioned by 85.2% of the women only 70% used to boil raw milk for 5-10 minutes after its effervescence. 113 J Egypt Public Health Assoc Vol. 84 No. 1 & 2, 2009 Knowledge and practices related to personal hygiene: Practicing personal hygiene was ranked as the first set of behaviors in maintaining the safety of food and reducing number of foodborne illnesses with washing hands before handling food received the highest rank.(23) The best knowledge score percentage among the studied women (73.8) was in their personal hygiene but their practice was with a lower score (71.3). There was a significant difference among different jobs only in the knowledge. This may be attributed to noticeable variations among their knowledge and practices in the proper hand washing and preparation of food during illness. The safe practice of washing hands before preparing food makes food poisoning less likely to occur. Hands should be washed with warm water and soap for at least 20 seconds.(24) Although all studied women agreed that hands should be properly cleaned before starting food preparation, using warm water and soap during hand washing, rubbing of finger tips, between fingers and around the wrist as well as washing the faucets’ handles were practiced by 20%, 71.1% and 46.3%; respectively. This indicates that large numbers of the women used not to properly clean their hands and used to contaminate them after hand washing. A study in Slovenia (2008) reported that 57.1% of respondents washed their hands properly with soap and warm water, although a significant number (33.9%) washed their hands with water only or did not wash at all (1.6%).(1) Not only persons suffering from food poisoning can contaminate the food, but also healthy carriers who carry normally a lot of food poisoning microorganisms e.g. E. coli, Staphylococcus aureus and Clostridium perfringens.(25)More than 114 J Egypt Public Health Assoc Vol. 84 No. 1 & 2, 2009 half of the sample (56.3%) considered diseased persons as a source of food contamination with food poisoning microorganisms and they should avoid food handling while ill (54.4%), but only 16.7% mentioned that they always avoid food handling during their illness since they are solely responsible for the food preparation for their family members. Also, about only one third of the studied women (33.7%) mentioned that apparently healthy persons can contaminate the food with food poisoning microorganisms. The limitations of this study included choosing the faculties and institutions that was based on personal communications. Also, food safety practices were assessed through self reporting. Self reporting usually overestimates the correct practices. RECOMMENDATIONS Food safety education should be launched to women and repeated at specific intervals to ensure that learnt information is put into the daily life practices. The information gained by this study can be used to formulate essential messages for such educational programs. REFERENCES 1. Jevsnik M, Hlebec V, Raspor P. Consumers’ awareness of food safety from shopping to eating. Food Control. 2008; 19: 737–45. 2. WHO. Food safety and foodborne illness. Fact sheet no 237. [cited 2009, January]. Available from: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs237/en/index.html 3. Anderson JB, Shuster TA, Hansen KE, Levy AS, Volk A. A camera’s view of consumer food-handling behaviors. J Am Diet Assoc. 2004; 104(2): 186– 91. 115 J Egypt Public Health Assoc Vol. 84 No. 1 & 2, 2009 4. FAO/WHO. Codex Alimentarius: basic text on food hygiene. 3rd ed. Italy: FAO/WHO; 2003. 5. McCarthy M, Brennan M, Kelly AL, Ritson C, de Boer M, Thompson N. Who is at risk and what do they know? Segmenting a population on their food safety knowledge. Food Quality and Preference. 2007; 18(2): 205–17. 6. Day C. Gastrointestinal disease in the domestic setting: what can we deduce from surveillance data?. J Infection. 2001; 43(1): 30–5. 7. WHO. Food safety: an essential public health issue for the new millennium. Geneva: WHO; 1999. 8. Fawzi M. Study of some foodborne diseases in Alexandria. Thesis: MPHSc (Food hygiene and control). Alexandria: Alexandria University, High Inst Publ Hlth; 1995. 9. Fawzi M. Investigation of bacterial food poisoning outbreaks in Alexandria. Thesis: DrPHSc (Food hygiene and control). Alexandria: Alexandria University, High Inst Publ Hlth; 1999. 10. Medeiros LC, HillersVN, Chen G, Bergmann V, Kendall P, Schroeder M. Design and development of food safety knowledge and attitude scales for consumer food safety education. J Am Diet Assoc. 2004;104: 1671–7. 11. Unusan N. Consumer food safety knowledge and practices in the home in Turkey. Food Control. 2007; 18: 45–51. 12. Patil SR, Cates S, Morales R. Consumer food safety knowledge, practices, and demographic differences: findings from a meta-analysis. J Food Protection. 2005; 68(9): 1884–94. 13. Streiner DL, Norman GR. Health measurement scales. 2nd ed. Oxford, New York, Tokyo: Oxford University Press; 1995: 104-43. 14. Angelillo IF, Foresta MR, Scozzafava C, Pavia M. Consumers and foodborne diseases: knowledge, attitudes and reported behavior in one region of Italy. International Journal of Food Microbiology. 2001; 64: 161–6. 15. Sudershan RV, Subba Rao GM, Rao P, Vishnu Vardhana Rao M, Polasa K. Food safety related perceptions and practices of mothers: a case study in Hyderabad, India. Food Control. 2008; 19(5): 506–13. 116 J Egypt Public Health Assoc Vol. 84 No. 1 & 2, 2009 16. Griffith CJ, Worsfold D, Mitchell R. Food preparation, risk communication and the consumer. Food Control. 1998; 9(4): 225–32. 17. Mead PS, Slutsker L, Dietz V, McCaig LF, Bresee JS, Shapiro C, et al. Food related illness and death in the United States. Emerg Infect Dis. 1999; 5(5): 607-25. 18. Redmond EC, Griffith CJ. Consumer food handling in the home: a review of food safety studies. J Food Protection. 2002; 66(1): 130–61. 19. Wilcock A, Pun M, Khanona J, Aung M. Consumer attitudes, knowledge and behaviour: a review of food safety issues. Trends in Food Science and Technology. 2004; 15: 56–66. 20. Badrie N, Gobin A, Dookeran S, Duncan R. Consumer awareness and perception to food safety hazards in Trinidad, West Indies. Food Control. 2006; 17: 370–7. 21. Jevsnik M, Hoyer S, Raspor P. Food safety knowledge and practices among pregnant and non-pregnant women in Slovenia. Food Control. 2008; 19: 526–34. 22. Byrd-bredbenner C, Abbot JM, Wheatley V, Schaffner D, Bruhn C, Blalock L. Risky eating behaviors of young adults—implications for food safety education. J Am Diet Assoc. 2008;108:549-52. 23. Medeiros LC, Kendall P, HillersVN, Chen G, Schroeder M. Identification and classification of consumers food handling behaviors for food safety education. J Am Diet Assoc. 2001;101(11):1326-39. 24. Karabudak E, Bas M, Kiziltan G. Food safety in the home consumption of meat in Turkey. Food Control. 2008; 19: 320–7. 25. Trickett J. Prevention of food poisoning. 4th ed. UK: Nelson Thrones; 2001. p. 18-24. 117