16.5 ADDITIONAL EXAMPLES

advertisement

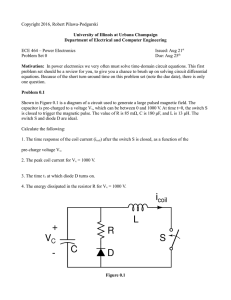

16.5 A D D I T I O N A L E X A M P L E S For review purposes, more examples of both piecewise linear and incremental analysis are given in the following subsections. No new material is presented, so readers who do not need additional practice can omit this section without loss of continuity. 16.5.1 P I E C E W I S E L I N E A R E X A M P L E : CLIPPING CIRCUIT The output voltage vo in the diode clipper circuit, shown in Figure 16.21a, will resemble the input voltage vi , except that the bottom of the waveform will be clipped off. The circuit has only one diode, so that the Thévenin solution method discussed in Chapter 3.6.1 can be used, but here we will use the method of assumed diode states. Assume that the diode in Figure 16.21 is ideal, then draw the two subcircuits, one with the diode OFF, and the other with the diode ON, as shown in Figures 16.21b and 16.21c. By inspection, the output voltage with the diode OFF is constant, because there is a fixed current IO flowing up through R. Thus vo1 = −IO R. (16.35) The current source and the voltage source are in series, so the voltage source has no effect on vo1 . Furthermore, when the diode is OFF, vi = vo1 + vD . (16.36) Because the diode is in the OFF state, vD must be negative. It follows that in the OFF state vi must always be more negative than −IO R. Next, when the diode is ON, the output is directly connected to the input: vo2 = vi . (16.37) In the ON state, vi must be more positive than −IO R. Hence the valid portions of the waveforms in the subcircuits are the darkened segments, and the complete output waveform is as shown in Figure 16.21d. As promised, the circuit has clipped off the bottom of the input wave. 16.5.2 E X P O N E N T I A T I O N C I R C U I T The circuit shown in Figure 16.22 produces an output voltage vOUT that is proportional to the exponential of the input voltage vIN for sufficiently large vIN . To analyze this circuit, assume that the Op Amp is ideal, the saturation current of the diode is Is = 10−12 A, and the temperature of the diode is approximately 29◦ C so that its thermal voltage is VTH = 26 mV. Because 918f IO + + vi - R vo vo1 (a) vi IO t iD = 0 + + vi - vD - + R -IOR vo1 (b) - Valid for vi < -IOR vo2 F I G U R E 16.21 Diode clipper. IO + + vi - vi = vo2 t - + vD = 0 R Valid for vi > -IOR -IOR vo2 (c) vo vo t -IOR (d) vi 918g R = 100 kΩ iD + F I G U R E 16.22 A diode-based exponentiation circuit. vIN + vOUT + - - the Op Amp is ideal, and used in a stable negative-feedback configuration, the voltage at the inverting terminal of the Op Amp is zero. As a result, iD = Is evIN /VTH − 1 = 10−12 A evIN /(26 mV) − 1 . For sufficiently large vIN , for example for vIN ≥ 120 mV, the exponential term dominates, and this relation simplifies to iD ≈ 10−12 A evIN /(26 mV) . Next, because the voltage at the inverting terminal of the Op Amp is zero, and because the current into that terminal is zero, the output voltage is given by vOUT = −RiD ≈ −10−7 V evIN /(26 mV) , which exhibits an exponential dependence on vIN . For example, for vIN = 200 mV, 300 mV, and 400 mV, vOUT = −0.219 mV, −10.3 mV, and −480 mV, respectively. 16.5.3 P I E C E W I S E L I N E A R E X A M P L E : L I M I T E R The circuit in Figure 16.23 is useful for making square waves out of sine waves, and for limiting the amplitude of an output waveform when the input waveform amplitude varies over a wide range. To analyze the circuit, we note that the Thévenin approach is not helpful, and a graphical solution might be messy because of the two diodes (not so, in fact, but that is not obvious yet). So resort to analysis by assumed diode states. The subcircuits for the four states, assuming an ideal-diode model, are shown in Figures 16.23b, 16.23c, 16.23d, and 16.23e 918h R D1 + V - + vi - D2 + V vo + - (a) Limiter circuit vo1 vi R + + +v OFF v- D1 OFF D2 vo1 + V V+ - + vi - +V t 0 -V (b) Both diodes OFF vo2 R + vi - + V - + OFF vo2 V + - +V t 0 (c) D1 ON F I G U R E 16.23 Diode limiter. vo3 R + OFF + V- + vi - V + vo3 - (d) D2 ON -V t 0 vo vi R + vi - ON + V - + ON - vo4 V + - (e) Both diodes ON vo 0 t (f) Complete waveform 918i along with the appropriate subcircuit output voltages, obtainable by inspection. From Figure 16.23b, vo1 = vi (16.38) because there is no current through R. When either diode is ON, the output voltage is independent of the source voltage vi . For D1 , ON, for example, vo2 = V. The fourth diode state, Figure 16.23e, cannot be reached with this topology, (assuming V is a positive quantity) because there is no value of vi that will force both diodes ON at the same time. Now we must identify the valid segments of these waveforms. In Figure 16.23b, both diodes are assumed OFF, so vd1 and vd2 must both be less than zero. Hence, using KVL: vi − V = vD1 < 0 (16.39) vi < V (16.40) −vi − V = vD2 < 0 (16.41) vi > −V. (16.42) Thus vi must be between −V and +V. Likewise vo1 , from Equation 16.38. This range of validity is indicated by the darkened segments of the waveform in Figure 16.23b. It follows that the complete output wave must be as shown in Figure 16.23f. If the peak amplitude of vi is ten or twenty times V, then vo is a reasonable approximation of a square wave. 16.5.4 E X A M P L E : F U L L - W A V E D I O D E B R I D G E Figure 16.24 shows one of the most common rectifier circuits found in electronic equipment, the full-wave diode bridge. We assume therefore that vi is a 60-Hertz sinusoid with 10-volt peak amplitude, and we wish to find the waveform vo across the output resistor. A full-blown assault using assumed diode states would yield 16 subcircuits, but it will turn out that only two of these are possible, suggesting a more insightful approach. Suppose that vi is a small positive voltage. Then current must flow down through the bridge. The only available path is D1 , RL , and D4 , because of the orientation of D3 and D2 . Similarly, for vi negative, current must flow up, and thus must follow the path D3 , RL , D2 . The two corresponding subcircuits, assuming ideal diodes, are shown in Figures 16.24b and 16.24c. Now, by inspection, for vi positive, vo = vi (16.43) vo = −vi . (16.44) and for vi negative, 918j D1 + vi - RL (a) + vi - D2 + vo - D3 + voA D3 OFF (b) Subcircuit for vi positive D1 OFF - D4 + vi - D1 OFF v + oB D4 OFF (c) Subcircuit for vi negative vi + vi - + voC - D3 OFF D4 OFF F I G U R E 16.24 Full-wave diode bridge. (d) D1 and D2 ON vo t t (e) All other subcircuits are degenerate. Consider, for example, the subcircuit for both D1 and D2 ON, as in Figure 16.24d. Clearly no current can flow in RL . Also, current can’t flow down through D3 , or up through D4 , so all diode currents must be zero in this state. A similar argument holds for all adjacent diode pairs, whether ON or OFF. Hence the two states depicted in Figures 16.24b and 16.24c are the only ones we need to consider. Note that the current always flows in the same direction through RL , regardless of the polarity of vi . For sinusoidal input the waveforms appear as in Figure 16.24e. The circuit is called a full-wave rectifier because current flows through RL on both halves of the input wave. Neglecting diode voltage drops, the average value of the output voltage, that is the DC voltage, is 0.637 times the peak of the input sinusoid. Further, by symmetry there is no frequency component in the output waveform at the input frequency, 60 Hertz in our example, or odd multiples thereof. Hence the circuit has a much higher percentage of DC relative to harmonics compared to the half-wave rectifier discussed in Section 4.3. 918k R i + i F I G U R E 16.25 Zener-diode regulator. + - v v + - 50 mV AC vo 20 V DC (a) (b) 16.5.5 I N C R E M E N T A L E X A M P L E : Z E N E R - D I O D E REGULATOR All semiconductor diodes will break down and conduct appreciable current under reverse bias conditions if the reverse voltage across the diode is large enough. This breakdown is non-destructive if the current is not excessive; the diode returns to normal reverse-bias behavior if the voltage is reduced. A Zener diode is a semiconductor diode in which this breakdown under reverse bias is carefully controlled by the manufacturing process so that the breakdown occurs at a specified voltage, the so-called Zener voltage of the diode. A typical v i curve is shown in Figure 16.25a. Because the breakdown voltage of a Zener diode can be carefully controlled by the manufacturing process, and the incremental resistance in the breakdown region is quite small (around 10 to 50 ), Zener diodes are quite useful as voltage regulators. A simple example is shown in Figure 16.25b. Equation 4.74 is clearly inappropriate for finding the incremental resistance in breakdown, because this part of the characteristic is not an exponential. Hence the value must be obtained from the data sheet for the Zener diode in question. Integrated-circuit regulators, with transistors, Zener diodes, and resistors all on a single chip, will certainly outperform either of the crude regulator circuits discussed here. 16.5.6 I N C R E M E N T A L E X A M P L E : DIODE ATTENUATOR It should be clear from Section 4.5, and particularly from Equations 4.63 and 4.74, that for small increments of voltage or current, the semiconductor diode looks like a linear resistor whose value depends on the DC current flowing through it. Thus it should be fairly easy to build an attenuator with an attenuation constant that can be changed by means of an external voltage or current. Figure 16.26 shows a simple example. Here a diode is used in the shunt branch of a voltage divider on a small-signal source vi . The DC current through the diode is controlled by the DC voltage VC through the large 918l RC Rt = R1||RC R1 + VC - R1 - + VOC = VC ------------------R1 + RC - + vi - (a) (c) F I G U R E 16.26 Diode attenuator. RC RC + VC - + - 0.6 V Rd R1 + R1 0 ID0 (b) + vi - (d) vo rd - resistor RC . If we assume that vi produces less than a 5 mV change in the diode voltage, then the incremental analysis approach discussed in Section 4.5 can be applied. First, draw the circuit for the calculation of the DC current ID0 is to form the Thévenin equivalent of the linear part of the circuit, as shown in Figure 16.26b. An easy way to solve for ID0 is to form the Thévenin equivalent of the linear part of the circuit, as shown in Figure 16.26c. At the same time we replace the diode by its piecewise linear model. Then ID0 = (VOC − 0.6) Rt + R d . (16.45) The incremental resistance rd of the diode will thus be a function of VC : rd = kT qID0 kT (R1 RC ) + Rd . = q VC R1 − 0.6 (16.46) (16.47) R1 +RC Now draw the subcircuit that relates the incremental variables. Replace the diode in Figure 16.26a by the incremental resistance rd , and set all DC sources, in this case VC , to zero, as indicated in Figure 16.26d. By inspection, vo = vi RC rd R1 + (RC rd ) . (16.48) The attenuation is clearly dependent on the DC voltage VC , as desired. 918m