Spain - University of York

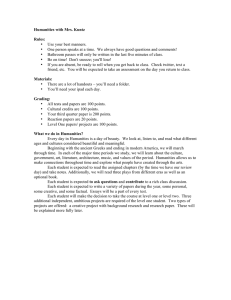

advertisement