Basis of Design - ASHRAE Journal, October 2013

advertisement

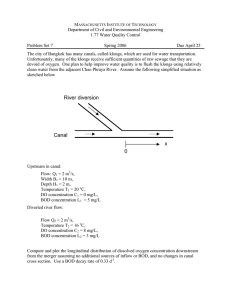

TECHNICAL FEATURE ©ASHRAE www.ashrae.org. Used with permission from ASHRAE Journal, October 2013 at www.atkinsglobal.com. This article may not be copied nor distributed in either paper or digital form without ASHRAE’s permission. For more information about ASHRAE, visit www.ashrae.org. Technical vs. Process Commissioning Basis of Design BY VINCE BRIONES, P.E., MEMBER ASHRAE; AND DAVE MCFARLANE, MEMBER ASHRAE The basis of design (BOD) document provides building designers and engineers with an effective tool they can use to clearly present—to the owner, commissioning agent (CxA), contractors, suppliers, and any other third parties—the decision, assumptions, and specifications that are being used to develop the construction documents for a project. The BOD transforms the raw data from the owner’s project requirements (OPR) document (the “what”) into a detailed, technical, actionable plan (the “how”) that will meet the owner’s objectives—which will also help avoid the “scope creep” that can derail the project schedule and lead to budget overruns. Understanding the Basis of Design ASHRAE defines the BOD as “a document that records the major thought processes and assumptions behind design decisions made to meet the owner’s project requirements (OPR).” The design team uses the BOD document to show how their assumptions and specifications will enable the completed project to satisfy the requirements listed in the OPR document. The previous article in this series (ASHRAE Journal, August 2013) noted that the owner can use a well-crafted OPR document as a checklist or “scorecard” to verify project success. The BOD document needs to be created early on: after the schematic design is completed, but before creating the actual design development documents. That’s because the BOD must explain the decision processes behind the design, essentially “translating” the owner’s *This is the third in a series of articles that explain the technical commissioning process for new buildings. The series (and the first article) is titled “Technical Commissioning: The Commissioning Process that Works.” Some of these articles’ content is based on ASHRAE Guideline 0-2005, The Commissioning Process (published 2005) and the National Environmental Balancing Bureau (NEBB) Whole Building Systems Technical Commissioning Procedural Standards Manual (revised April 2013). In addition, some of the information in this article has been taken from an unpublished NEBB standard titled NEBB Standard Owner’s Project Requirements (OPR) Guideline (June 20, 2011). This article also draws upon an unpublished “sample” OPR document created by NEBB for the fictional “ABC Headquarters Office Building” (Jan. 2, 2011). vision into practical design criteria—and improving the communication process between all parties during the design phase. As noted in the previous article, the USGBC has made the OPR and BOD documents mandatory for all LEED-NC certified projects (LEED 2009). Unfortunately, the BOD document is too often forgotten until after the design process. Then something is thrown together—which ends up of no use to anyone. Without a BOD document, the CxA cannot fully understand and act upon the design team’s actual intentions. Some Practical Considerations To help ensure easy understandability by the most readers, write your BOD document in layman’s terms (whenever possible). Use lots of charts, tables, detailed lists, and graphs. If photos best explain what you want to convey, include them, along with clear and detailed captions. Every member of the design team should be a part of preparing the BOD document and then maintaining it throughout the design process. It’s not a job for a juniorlevel designer or intern. You’ll also need to involve the architectural team, as well as the mechanical, plumbing, and electrical engineers. And don’t forget specialty ABOUT THE AUTHORS Vince Briones, P.E., is senior program manager at Atkins in Austin, Texas, and Dave McFarlane is a principal project director at Atkins in Fort Myers, Fla. 76 A S H R A E J O U R N A L a s h r a e . o r g O CT O B E R 2 0 1 3 TECHNICAL FEATURE disciplines or consultants such as fire protection, security, and audio/ visual providers. You should factor BOD maintenance into your project schedule. Then update the document at regular milestones, such as the 30%, 60%, 90%, and 100% stages of submitting construction documents. A Case in Point TABLE 1 Sample HVAC design criteria. ITEM Building Ventilation DESIGN CRITERIA ••Minimum ventilation rates shall be 5 cfm per person and 0.06 cfm/ft2 of building surface; the ventilation rate for the entire building shall be 3,000 cfm. Building ventilation rate shall meet the minimum requirements of the latest version of ASHRAE Standard 62.1. ••Inside pressure. Ventilation and air conditioning systems shall maintain a positive pressure of 0.02 in. inside the building (compared to the exterior) to minimize air and dirt infiltration. The volume of fresh air shall be sufficient to maintain positive pressure inside the facility (compared to outside). ••Infiltration/exfiltration offset. An additional amount of conditioned air shall be included to offset the effects of infiltration and exfiltration. The allowable leakage rate at 50 Pa shall be 0.2 cfm/ft2 of building surface; maximum infiltration wind speed shall be 15 mph. ••Air filtration. Air-handling units shall include two stages of filtration: The pre-filter shall have a maximum efficiency reporting value (MERV) of 8 (per ASHRAE Standard 52.2-2007), and the final filter shall have a value of MERV 13. Units shall be sized and selected with respect to the dirty filter condition. Filters shall be of medium efficiency (30%), as defined by the latest version of ASHRAE Standard 52.2. There shall also be adequate space for filter removal and replacement. ••Outside air intakes shall be a minimum of 10 ft above the ground and a minimum of 15 ft away from any exhaust-air discharge openings or plumbing vents. Intakes shall be sized so free-air velocities fall below 500 fpm. Intakes shall be equipped bird screens, and with weatherproof and sand-removing louvers. Misunderstanding a project’s design intent is one of today’s most common construction-related challenges. And one of the greatest benefits of the BOD document is that its clear presentation of the owner’s design intent helps ••Noise levels. HVAC-generated noise shall not exceed NC 45 in the data center, NC 35 in protect the owner, the design team, circulation areas, and NC 30 in open offices, private offices, and conference rooms. HVAC Noise ••Duct velocities for systems of 2 in. of pressure and lower shall not exceed 1,200 fpm; the engineers, and the contractors Limitations velocities for systems greater than 2 in. shall not exceed 2,400 fpm. from confusion, misunderstandings, ••Fluid flow and pipe velocities shall be less than 6 fps for pipes less than 4 in. in diameter; and lost revenue. for pipes larger than 4 in., velocities shall be less than 8 fps. We once worked on a museum ••Minimal service interruption. The design shall enable the building’s main HVAC equipment to be serviced, maintained, and repaired with minimal interruption to building project for which the primary exhibfunctions. its were to be marble sculptures. ••Shutoff valves shall be provided at each coil. Equipment Early in the design phase—and after Servicing and ••Equipment mounting. All floor-mounted equipment shall rest on a 3-in.-thick (minimum) Access concrete housekeeping pad. The design shall employ vibration-isolating elastomeric pads to much debate—the owner’s authoreduce transmitted vibration. rized representative approved a wet••Accessibility. There shall be 3 ft of access space around each piece of mechanical equipment, as well as enough space to allow coils to be to be removed and replaced. pipe sprinkler system to save money. The discussion and the decision’s Smoke ••Control standards. Smoke detection and emergency automatic controls shall conform to Detection approval were noted in the BOD. the latest National Electrical Code (NEC) NFPA 90A and NFPA 72 standards. and Fire But shortly before the projPrevention ect went out for bid, one of the museum’s user groups protested that future exhibits result, the designers were able to charge a fair price for could require a dry-pipe fire protection system. The the required redesign services. group also cited the museum’s own design-standards Different Needs, Different Documents documents, which mandated dry-pipe fire protection. Sometimes architects and engineers confuse the BOD The use group further maintained that the fire protecdocument with the narratives they create during project tion engineer should have known about the dry-pipe pursuit. Design professionals sometimes say, “We don’t mandate, and should have included such a system as need to produce an additional document. We’ve already standard practice. But no one could recall why a wetprovided the owner with an RFP-based narrative that pipe system had been specified. describes our design plan.” Good news: Because the project had a thorough BOD It’s essential to understand that the RFP, the early document that clearly identified the wet-pipe system design narratives, the OPR, and the BOD are all differchange during the design, the fire protection engineer ent documents that serve different purposes. Without this was able to clearly show the owner how the wet-pipe understanding, the design team can be well into the decision was made. The owner then authorized the design process before the owner realizes the project has return to a dry-pipe system, and agreed that the design taken a turn that deviates from his or her requirements. team should not be expected to “eat” the change. As a O CT O B E R 2 0 1 3 a s h r a e . o r g A S H R A E J O U R N A L 77 TECHNICAL FEATURE TABLE 2 Sample indoor design criteria. SPACE TYPE SUMMER TEMP (°F DRY BULB) HUMIDITY (SUMMER/WINTER) WINTER TEMP (°F DRY BULB) PRESSURE RELATIONSHIP (PSI) CO 2 ABOVE AMBIENT (PPM) SOUND LEVEL (NC) VIBRATION LEVEL (IN./SEC) LIGHT LEVEL (FC) All Spaces (Except Utility Spaces And Data Center) Occupied: 75 Night Setback: 81 40%/Float Occupied: 70 Night Setback: 63 +0.01 to Hall 350 30 in Offices & Conference Room 30 in Open Cubicles 0.016 40 Utility Spaces (Such as Electrical & Mechanical) 10 Above Ambient 50% 63 +0.01 to Hall 350 40 0.032 30 Data Center 72 (No Night Setback) 35% (Summer & Winter) 72 (No Night Setback) +0.01 to Hall 350 45 0.008 30 [Adapted from NEBB’s unpublished sample OPR document (Jan. 2, 2011), p. 14. Vibration values based on Sound and Vibration Design and Analysis; NEBB, 1st Edition (1994).] And the later in the design phase that the owner calls for changes, the more expansive they become— and the more frustrated the owner becomes. TABLE 3 Sample lighting and electrical design criteria. Building the Document ITEM DESIGN CRITERIA ••Controls. The entire facility shall be on a timed lighting control system with photocells. Lighting shall also be controlled manually by local switches that have motion-controlled occupancy sensors. ••Lighting fixtures in offices, cubicles, conference rooms, break rooms, utility rooms, the lunchroom, and the data center shall be recessed, high-efficiency linear fluorescents with energy-saving, low-mercury lamps. Lobby lighting shall use metal-halide lamps, LED (lightemitting diode) downlights, and LED accent lights. Restrooms shall have LED downlights. ••Exit signage and emergency lighting shall be equipped with a 90-minute emergency battery pack. Exit signs shall use LED illumination. ••Light levels setpoints (in foot-candles) shall be 40 fc; except in the data center and mechanical, electrical, and storage rooms, which shall be 30 fc. ••Lighting heat gain. The heat gain from lighting fixtures shall be obtained from the lighting power density factors defined in the latest version of ANSI/ASHRAE/IES Standard 90.1, and shall be based on the actual lighting installed in the building. To ensure the BOD meets all of Interior Lighting the owner’s needs and desires, it should address in detail the design elements identified in both the RFP and the OPR. Hopefully, the OPR captured all of the owner requirements in the RFP, but it’s a good idea ••Lighting elements/power density. All exterior lighting shall employ LED lamps, and shall be designed to use less than at least 25% of the allowable lighting-power density based upon to review the OPR against the RFP. the latest version of ANSI/ASHRAE/IES Standard 90.1. Project description. As noted in Exterior ••Zones of illumination. All site lighting shall have minimal trespass over the property line. All Lighting exterior lighting shall comply with LZ3 zone requirements as defined by the latest version of the previous article, the OPR must IESNA RP-33L. serve as the source document for ••Fixtures shall be either pole- or wall-mounted, with angled shade to reduce light pollution. Total lumens above 90 degrees from nadir shall be less than 5%. the BOD. So the first major section of the BOD should be a restatement ••Design codes. The electrical design shall comply with the Minnesota Building Code, all applicable local codes, and the requirements of the latest version of NFPA 70. of the OPR’s project description—an Electrical ••Building utilization voltage shall be 277/480 volt, 3-phase, 4-wire. The calculated service overview of the building’s purpose Requirements size shall be 1,250 amperes. ••Grounding shall be in accordance with the latest version of NFPA 70, article 250. Raceway and essential functions. Be sure to systems shall be concealed, except in mechanical and utility areas. include the data from the key charts and tables in the OPR that will drive the design team’s efforts, such as the space utilization purposeful intent to preserve the owner’s requirements table, the outdoor design criteria table, the indoor in its design efforts. design considerations table, and the complete, updated Codes, standards, and specifications. Like the OPR, list of all authorized vendors, suppliers, and contractors. the BOD states that the building must comply with all You’ll also need to include an updated project schedapplicable federal, state, regional, county, city, and local ule in the BOD, and this section of the document is a codes, standards, and specifications. good place to display it. By capturing the overall project But unlike the more general statements in the OPR docdescription and key related information from the OPR ument, the BOD must include specific details for all of the document, the design team demonstrates not only its applicable codes and specifications that must be satisfied clear understanding of the project’s purpose—but its by every project discipline—that way both the design and 78 A S H R A E J O U R N A L a s h r a e . o r g O CT O B E R 2 0 1 3 Advertisement formerly in this space. TECHNICAL FEATURE the construction teams can take them TABLE 4 Sample building envelope design criteria. all into consideration. The sample ITEM DESIGN CRITERIA HVAC criteria here are based on stan••Fenestration percentage. The percentage of glass on the building’s exterior shall be 40%. dards adopted by Minneapolis. ••Window specifications. All exterior windows shall be specified to help prevent unwanted solar heat gain in summer, while still harnessing direct solar radiation in winter. Visible light transmitWhile the OPR might generally Windows tance (VLT) shall be at least 0.75. state that “the building will meet ••Insulating value. The U-value of all exterior windows shall be at least 0.55. all applicable ASHRAE standards,” ••The solar heat gain coefficient (SHGC) of all exterior windows shall be 0.40. the BOD must be more specific—so ••Interior wall panels shall be 5/8-in.-thick gypsum board over metal framing (16 in. on the designers know exactly which center). Walls ••Exterior curtain wall assemblies shall be double-pane insulated and fully climate-appropriate. code to follow in their designs. As a ••Insulating value. The maximum U-value of all exterior walls shall be 0.032. result, the BOD might state that the building “shall meet or exceed ANSI/ ••Framing. The roof shall be metal-framed. ••Overlayment material shall be ¼-in.-thick protection board. ASHRAE Standard 62.1-2010.” ••Moisture barrier shall be either white thermoplastic polyolefin (TPO) membrane or GalRoof By specifying the exact codes and valum® deck. standards required, the BOD identi••Insulation shall be entirely above deck with continuous layers of open-cell foam as needed to achieve a minimum rating of R-30. fies how the design team will meet the owner’s requirements. In addition, a careful delineation of codes and standards not only helps only minimally addressed in the previous article, that prevent “cutting corners,” but also helps answer questions doesn’t mean it shouldn’t be a key element of the BOD. about why something was designed in a certain manner. As with every aspect of the BOD, defining the envelope HVAC design. The BOD must explain how the buildcriteria must be a team effort. For example, a key enveing’s HVAC systems will be designed in accordance lope design element is establishing the sealing levels with the project RFP, the OPR, and all applicable codes, that will achieve the owner’s desired infiltration rate— standards, and regulations—as well as any other essenwhich is data that should come from the architect. Although a tial design criteria (which should also be described in mechanical engineer or energy modeler can evaluate the BOD). For example, the sample OPR in the previous the performance of various building materials, they may article called for “total energy consumption of less than not understand the physical or budgetary impacts of (for 70 kBtu/ft2 per year.” The BOD must explain how the example) changing a roof’s insulation specification from components will meet this requirement (Table 1). R-20 to R-40 (see Table 4 for sample criteria). Indoor and outdoor design. The OPR should include Utility baselines. The BOD should include projected detailed charts that describe the owner’s expectations monthly utility baselines for electrical, gas, and water for the building’s interior and exterior environments usage. These baselines—which you can extract from the (temperature, humidity, CO2 levels, etc.). The BOD must OPR—will provide a starting point for whatever monitoring restate those considerations and refine them as needed. tool the owner wants to use to track resource consumption. For this series we’re assuming our sample building Additional energy-usage factors. The BOD must also is being constructed in Minneapolis; so its indoor and address any other systems or equipment that will affect outdoor design criteria are based on ASHRAE data for the building’s energy use, such as loads for occupants, Minneapolis (see Table 2, Page 78, for sample criteria). miscellaneous equipment, and any specialty areas such Lighting and electrical systems. The previous article as kitchens, fitness rooms, and server rooms. made little mention of owner’s lighting expectations; but Sustainability goals. A key element of the BOD is a those specifications must be thoroughly documented in description of the owner’s sustainability goals. Typically, the OPR and BOD. Certainly, the building owner wants this includes the owner-mandated LEED rating, as well to maximize light output for occupant comfort. But the as the version of LEED to be used in the project. The owner also wants to minimize energy use and maintedescription should include specific details, such as: nance requirements. So the BOD must give the design “The facility is required to achieve LEED-NC Gold rating team the needed data to translate the owner’s desires into under LEED Version 3.0.” actionable design (see Table 3, Page 78, for sample criteria). LEED certification is not the sole responsibility of the Building envelope. While the building envelope was design team—every party and person involved in the project 80 A S H R A E J O U R N A L a s h r a e . o r g O CT O B E R 2 0 1 3 TECHNICAL FEATURE must actively support the owner’s efforts toward LEED certification. LEED certification is definitely a chain that is only as strong as its weakest link. Maintenance staff training. The requirements for the owner’s staff training that are defined in the OPR must be included in the BOD. Be sure to include details that show the amount of time that will be spent on training and the types and methods of training that are planned. Project delivery, budget, and milestones. It’s important to describe the project delivery method the owner intends. This could be a bid plan and specification, design-build, gross maximum pricing, or other method. Also include descriptions of the budget, all known required meetings, and project milestones—all of which should be obtainable from the OPR document. Additional design concerns. Many other design concerns must be captured in the BOD. Space doesn’t permit us to mention them all, but be sure to describe any BIM requirements, all specialized software (such as simulation tools for energy modeling), coordination of work between the various engineering disciplines, any desired measurement and verification programs, and any QC or QA processes the owner wants. Commissioning requirements. If the building isn’t properly commissioned, you probably won’t end up with a truly satisfied owner. So capture and update all of the commissioning requirements, and build the CxA’s building-specific requirements into the BOD. The commissioning scope of work table and the commissioning phases and responsibilities table should be key parts of the BOD. To ensure the building’s ongoing optimal performance, consider adding to the project plan a comprehensive annual “commissioning check-up.” Conclusion Like the OPR, the BOD is an interactive tool that must be revised as the owner and design team make decisions. Especially as the project evolves, and budget and time constraints enter the picture, you’ll need to adjust the OPR and the BOD documents. Remember, the owner’s requirements drive the basis of design; not the other way around! So don’t view the BOD as a burden. View it as a key element in an effective communication process—the kind of process that will help ensure that the owner’s voice is heard accurately—which is how the owner will end up with a building that meets expectations. Advertisement formerly in this space. O CT O B E R 2 0 1 3 a s h r a e . o r g A S H R A E J O U R N A L 81