Effects of Choice Framing and Affect on Delay of Gratification

advertisement

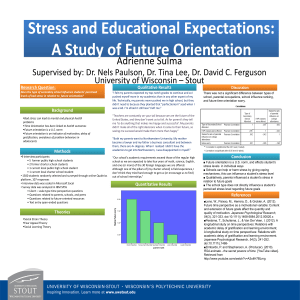

The Huron University College Journal of Learning and Motivation Volume 52 | Issue 1 Article 13 2014 Effects of Choice Framing and Affect on Delay of Gratification Kristina Waclawik Huron University College Follow this and additional works at: http://ir.lib.uwo.ca/hucjlm Part of the Psychology Commons Recommended Citation Waclawik, Kristina (2014) "Effects of Choice Framing and Affect on Delay of Gratification," The Huron University College Journal of Learning and Motivation: Vol. 52: Iss. 1, Article 13. Available at: http://ir.lib.uwo.ca/hucjlm/vol52/iss1/13 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Psychology at Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Huron University College Journal of Learning and Motivation by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact jpater22@uwo.ca. CHOICE FRAMING AND AFFECT IN DELAY OF GRATIFICATION 181 Effects of Choice Framing and Affect on Delay of Gratification Kristina Waclawik Huron University College at Western Abstract Previous research on delay of gratification indicates that people have a tendency to choose small rewards that are available immediately over more valuable rewards that are available after a certain amount of time. This ability to wait for the more valuable reward has been associated with a variety of positive outcomes, such as better self-regulation abilities, academic success, and reduced risk of addiction. One theory evoked to explain the inability to delay gratification states that an emotional, impulsive “hot” system overrides a rational, cognitive “cool” system and influences the person to act impulsively and choose the small immediate reward. Various factors affecting how the desired reward is presented can differentially activate the cool system to a greater extent that the hot system. The role of affect in this decision-making process is unclear as a result of contradicting evidence. The present study, using a between-subjects design, used a modification of the Velten mood statements to induce positive and negative affect, and attempted to activate the cool system to a greater extent than the hot system by presenting the choice in an impersonal manner. There were no significant differences between the different conditions. Methodological flaws of the study are discussed. Delay of gratification refers to the ability to wait a specified period of time for a large reward instead of receiving a smaller reward immediately (Metcalfe & Mischel, 1999). Delay discounting refers to the phenomenon in which the value of the larger reward decreases as the delay for obtaining that reward increases (Metcalfe & Mischel, 1999). Delay of gratification was first studied extensively in children (Metcalfe & Mischel, 1999); in a typical paradigm, a child is presented with a reward such as candy or a toy, and informed that she can have two of the desired items if she waits a specified amount of time (e.g. 15 minutes), or can choose to stop waiting and receive the one item in front of her at any time (Metcalfe & Mischel, 1999). Typically, the child will choose to wait, as two rewards are preferable to one, but over the waiting period the temptation to receive a reward immediately often becomes overwhelming and CHOICE FRAMING AND AFFECT IN DELAY OF GRATIFICATION 182 many children eventually choose to take the single item immediately (Metcalfe & Mischel, 1999). In adults, the task is often modified to involve choices between hypothetical amounts of money (Green, Myerson, Lichten, Rosen, & Fry, 1996). The ability to delay gratification in this type of paradigm is thought to be reflective of broader competencies (Metcalfe & Mischel, 1999), such as intelligence, resistance to temptation, and social responsibility (Mischel, Shoda, & Rodriguez, 1989). Delay of gratification in adults has been correlated with college GPA’s (Kirby, Winston, & Santiesteban, 2005) and SAT scores (Mischel et al., 1989), and negatively correlated with addictive behaviours (Bickel & Marsch, 2001; Kirby, Petry, & Bickel, 1999). The evidence that laboratory tests of delay of gratification have high relevance in real-world measures of self-regulation (Metcalfe & Mischel, 1999) highlights the importance of gaining knowledge of the factors that affect people’s ability to wait for a more valuable outcome. Metcalfe and Mischel (1999) propose that this choice elicits competition between a “hot”, emotional, impulsive system and a “cool”, cognitive system. In delay of gratification tasks, the hot system influences the individual to act impulsively and select the immediate, less desirable reward, while the cool system influences her or him to act rationally and wait for the more desirable reward (Metcalfe & Mischel, 1999). Each system can dominate the other one, depending on various individual and situational factors (Metcalfe & Mischel, 1999). For example, how the stimulus of choice is presented can influence whether the hot or cool system is predominantly activated (Metcalfe & Mischel, 1999). In a cool presentation of the stimulus, the stimulus is presented in such a way that cool information about the object – for example, its colour, shape and name – is available, but the hot information – for example, the feelings elicited by eating it, if it is a food reward – is not as readily available (Metcalfe & Mischel, 1999). For example, presenting a picture of the stimulus (cool presentation) in the place of the actual CHOICE FRAMING AND AFFECT IN DELAY OF GRATIFICATION 183 stimulus (hot presentation); in such tasks, delay time is increased (Metcalfe & Mischel, 1999). Delay time is also increased when the reward is out of sight during the wait period (Mischel & Ebbesen, 1970), another situation in which the hot information is less accessibly (Metcalfe & Mischel, 1999). Activation of the hot system can also be inhibited when attention is focused elsewhere during the delay period (Metcalfe & Mischel, 1999). For example, children who were given a toy to play with during the delay were much more likely to wait for the larger reward than those without a toy (Mischel, Ebbesen, & Zeiss, 1972). Children who distracted themselves by decreasing attention to the reward and increasing attention elsewhere in the room were more successful at waiting than those who did not deploy attention elsewhere (Rodriguez, Mischel & Shoda, 1989). All of these are thought to be situations in which ability to delay gratification is enhanced due to greater activation of the cool system than the hot system (Metcalfe & Mischel, 1999). Although various individual and situational factors affecting the tendency to delay gratification have been studied (Metcalfe & Mischel, 1999), there is a paucity of research on the role of affect. One study found that induced positive mood increased delay discounting in extroverts (Hirsh, Guindon, Morisano, & Peterson, 2010). The authors hypothesized that this was due to a preferential activation of the hot, emotional system in extroverts than in introverts (Hirsh et al., 2010). However, another study with children found that those in whom a positive mood was induced showed decreased discounting in comparison to negative-mood participants (Moore, Clyburn & Underwood, 1976). In this case, the effect was explained by the hypothesis that people in a positive mood are more likely to act rationally, while those in a negative affect will seek anything that will immediately alleviate the negative state (Moore et al., 1976). The CHOICE FRAMING AND AFFECT IN DELAY OF GRATIFICATION 184 effects of mood on delay discounting are unclear and the present study will attempt to elucidate this ambiguity. The purpose of the present study is to examine another possible mechanism of activating the cool system over the hot system, and to further elucidate the effects of mood states on delay of gratification. It was hypothesized that framing the delay task in a non-personalized manner (i.e. as a choice another individual must make rather than a choice the participant must make) will result in higher delay of gratification because this would result in preferential activation of the cool system and therefore increased ability to delay, as the non-personal presentation would elicit cool information about the stimulus without the corresponding hot information. Appetitive, hot information was hypothesized to be less available due to the removal of a personal perspective on the stimulus (rather than imagining themselves receiving the reward, the participants will be imagining a different person receiving it). In addition, the effects of positive and negative moods on delay of gratification will be examined. It was hypothesized that mood will have more of an effect on the participants who received the delay choice framed as a personal choice, because their hot, emotional systems will already be activated and therefore they will be more responsive to emotional cues. Furthermore, in keeping with Moore et al.’s (1976) theory, the positive mood was expected to produce greater delay of gratification than the negative mood due to greater ability to act rationally rather than emotionally and impulsively when in a positive mood. CHOICE FRAMING AND AFFECT IN DELAY OF GRATIFICATION 185 Method Participants Twenty-six participants took part in the study. Nine of these were students at Huron University College and participated in exchange for partial course credit in an introductory psychology course. The remaining were recruited via word-of-mouth. Materials A sub-set of the Velten mood induction statements, obtained from Seibert and Ellis (1991), were used to induce positive and negative moods. There were twenty-five statements each in the positive and negative conditions, and each statement was presented individually for six seconds via PowerPoint. The order of the statements was randomized for each participant, and a slide containing instructions to read the statements and try to feel the mood conveyed by them appeared at the beginning of the PowerPoint for every participant. The delay of gratification task was a modified version of that used by Green et al. (1996), in which participants were presented with a series of hypothetical choices between receiving certain amount of money immediately, or $1000 in one year (see Appendix A). The choices of the immediate reward ranged from $100 to $1000 and were always presented sequentially, although they randomly alternated between ascending and descending between participants. In the personal choice condition, the instructions before the first choice read as follows: “Imagine you are going to make some choices between different amounts of money. For each choice, please select the alternative you would choose in a real life situation. Which would you choose?”. In the impersonal choice condition, the instructions read as follows: “Imagine a friend of yours is going to make some choices between different amounts of money. For each choice, CHOICE FRAMING AND AFFECT IN DELAY OF GRATIFICATION 186 please select the alternative you would advise your friend to choose. Which would you advise a friend to choose?” Procedure After giving informed consent, participants were seated at a computer, presented with the mood-induction PowerPoint, and instructed by the experimenter to follow the instructions presented on the screen and inform the experimenter when the PowerPoint was finished. After participants had sat through the PowerPoint, the experimenter presented them with the delay of gratification task, again instructing them to follow the instructions on the screen. The entire procedure took approximately 15 minutes. Results A 2 x 2 ANOVA was conducted with mood (with two levels: positive and negative) and choice framing (with two levels: personal and impersonal) as the independent variables and amount at which the switch from the delayed to the immediate reward was preferred as the dependent variable. There was no main effect of mood, F(1, 21) = 2.07, p > 0.05, no main effect of choice, F(1, 21) = 0.81, p > 0.05, and no mood by choice interaction, F(1, 21) = 0.71, p > 0.05. The results are displayed in Figure 1. Discussion Delay of gratification paradigms test an individual’s preference for a small reward delivered immediately over a large reward received after a specified period of time (Metcalfe & Mischel, 1999). Research indicates that the value of a large reward tends to decrease when people must wait a certain period of time before receiving it, up to the point that many people will choose a smaller reward immediately rather than wait for the larger reward (Metcalfe & Mishcel, 1999). One theory that attempts to explain this illogical preference refers to the CHOICE FRAMING AND AFFECT IN DELAY OF GRATIFICATION 187 1000 900 800 Immediate reward ($) 700 600 Impersonal 500 Personal 400 300 200 100 0 Positive Negative Figure 1. Mean amount at which immediate reward was preferred over delayed reward for each condition. No differences were significant. CHOICE FRAMING AND AFFECT IN DELAY OF GRATIFICATION 188 dichotomy between a hot, emotional system that bases decisions after emotions and impulses and a cool system that influences decisions to be rational (Metcalfe & Mischel, 1999). The tendency to act irrationally and choose the small, immediate reward can be mitigated when the cool system is activated over the hot system by presenting factual information which the cool system responds to instead of appetitive information which the hot system responds to (Metcalfe & Mischel, 1999). Another possible modulator of ability to delay gratification is affect, although the effects of positive versus negative affect are less clear. Based on a previous study with children in which positive mood lead to greater ability to delay gratification, it has been theorized that a positive mood encourages rational thinking while a negative mood encourages impulsive actions, influenced by the desire to select the option that will immediately relieve negative affect (Moore et al., 1976). The present study sought to examine another possible method of increasing ability to delay gratification by activating the cool system over the hot system by presenting the choice as an impersonal rather than a personal choice, and sought to replicate the previous finding of the effects of mood (Moore et al., 1976). Unexpectedly, there were no differences between any of the conditions and no interaction effect. It is quite possible that this lack of effect was due to the low number of participants in each condition and then a stronger effect would be seen in a study using more people. It is also possible that, although the premises for both conditions were correct, the actual manipulations themselves were not strong enough to elicit an effect. For example, although the modified Velten mood statements used in the present study have previously been found to reliably induce the desired mood (Jennings, McGinnis, Lovejoy, & Sterling, 2000; Seibert & Ellis, 1991), the Velten statements are not as reliable at eliciting a particular affective state as other mood induction techniques (Westermann, Spies, Stahl, & Hesse, 1996). Furthermore, the Velten CHOICE FRAMING AND AFFECT IN DELAY OF GRATIFICATION 189 statements have been shown to be more reliable at eliciting a negative mood than a positive one (Westermann et al., 1996), so it is possible that the comparison was actually between a negative mood and a neutral mood rather than a negative mood and a positive mood. This would not totally explain the lack of effect, of course, for if there really was an effect of mood a negative mood would be expected to differ from a neutral one. However, the difference between a negative and neutral mood would be smaller than that between a negative and positive mood which could have contributed to the lack of effect in conjunction with the other attenuating factors. The personal choice manipulation may also not have been strong enough to elicit the expected effect, perhaps because the choices in both conditions were hypothetical and thus were less likely to activate the hot, impulsive system. Delay of gratification tasks are somewhat more difficult to examine in adults because of the differences in what adults find rewarding versus what children find rewarding (Green et al., 1976), but the effect may be present in a task that involves real rather than hypothetical choices. The ability to delay gratification in order to receive a more valuable reward after a specified period of time rather than a less valuable one immediately is related to a variety of positive outcomes such as self-regulation abilities (Mischel et al., 1989), academic success (Kirby et al., 2005; Mischel et al., 1989) and reduced risk of developing addictions (Bickel & Marsch, 2001; Kirby et al., 1999). Therefore the study of what factors contribute to this ability is important as it can facilitate an increase in this ability in individuals who do not have it. The present study did not find that framing a choice as an impersonal one or putting participants in a positive mood improved this ability, but future studies with improved methodology may yet find such results. CHOICE FRAMING AND AFFECT IN DELAY OF GRATIFICATION 190 References Bickel, W.K., & Marsch, L.A. (2001). Toward a behavioural economic understanding of drug dependence: Delay discounting processes. Addiction, 96, 73-86. Green, L., Myerson, J., Lichtman, D., Rosen, S., & Fry, A. (1996). Temporal discounting in choice between delayed rewards: The role of age and income. Psychology and Aging, 11, 79-84. Hirsh, J.B., Guindon, A., Morisano, D., & Peterson, J.B. (2010). Positive mood effects on delay discounting. Emotion, 10, 717-721. Jennings, P.D., McGinnis, D., Lovejoy, S., & Stirling, J. (2000). Valence and arousal ratings for Velten mood induction statements. Motivation and Emotion, 24, 285-297. Kirby, K.N., Petry, N.M., & Bickel, W.K. (1999). Heroin addicts have higher discount rates for delayed rewards than non-drug-using controls. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General., 128, 78-87. Kirby, K.N., Winston, G.C., & Santiesteban, M. (2005). Impatience and grades: Delay-discount rates correlate negatively with college GPA. Learning and Individual Differences, 15, 213-222. Metcalfe, J., & Mischel, W. (1999). A hot/cool-system analysis of delay of gratification: Dynamics of willpower. Psychological Review, 106, 3-19. Mischel, W., & Ebbesen, E.B. (1970). Attention in delay of gratification. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 16, 239-337. Mischel, W., Ebbesen, E.B., & Zeiss, A.R. (1972). Cognitive and attentional mechanisms in delay of gratification. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 21, 204-218. Mischel, W., & Moore, B. (1973). Effects of attention to symbolically presented rewards on selfcontrol. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 28, 172-179. Mischel, W., Shoda, Y., & Rodriguez, M.L. (1989). Delay of gratification in children. Science, 244, 933-938. Moore, B.S., Clyburn, A., & Underwood, B. (1976). The role of affect in delay of gratification. Child Development, 47, 273-276. Rodriguez, M.L., Mischel, W., & Shoda, Y. (1989). Cognitive person variables in the delay of gratification of older children at risk. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57, 358-367. Seibert, P.S., & Ellis, H.C. (1991). A convenient self-referencing mood induction procedure. Bulletin of the Psychonomic Society, 29, 121-124. Westermann, R., Spies, K., Stahl, G., & Hesse, F.W. (1996). Relative effectiveness and validity of mood induction procedures: A meta-analysis. European Journal of Social Psychology, 26, 557-580. CHOICE FRAMING AND AFFECT IN DELAY OF GRATIFICATION Appendix A Delay Discounting Task 1. Would you rather have: $1000 today OR $1000 in 1 year 2. Would you rather have: $950 today OR $1000 in 1 year 3. Would you rather have: $900 today OR $1000 in 1 year 4. Would you rather have: $800 today OR $1000 in 1 year 5. Would you rather have: $700 today OR $1000 in 1 year 6. Would you rather have: $600 today OR $1000 in 1 year 7. Would you rather have: $500 today OR $1000 in 1 year 8. Would you rather have: $400 today OR $1000 in 1 year 9. Would you rather have: $300 today OR $1000 in 1 year 10. Would you rather have: $200 today OR $1000 in 1 year 11. Would you rather have: $100 today OR $1000 in 1 year The first choice alternated randomly between ascending and descending. 191 CHOICE FRAMING AND AFFECT IN DELAY OF GRATIFICATION Appendix B ANOVA Summary Table Degrees Partial Source of Sums of of Mean Eta variance Squares Freedom Squares F ratio P value Squared Mood 193436.2 1 193436.2 2.073 0.165 0.09 Choice 75480.01 1 75480.01 0.809 0.379 0.037 Mood * Choice 15917.97 1 15917.97 0.171 0.684 0.008 Error 1959619 21 93315.19 Total 1.57E+07 25 192

![[100% HDQ]**[VIDEO] Sully Full HD online streaming Watch](http://s2.studylib.net/store/data/018201909_1-d9e42526408b40da0a9798833ad4d3be-300x300.png)