Presidential Authority under Section 337, Section 301, and the

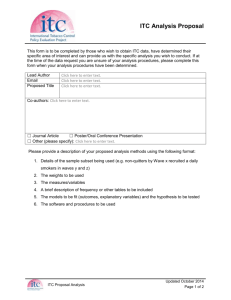

advertisement