(2015). Grandparent childcare and labour market participation in

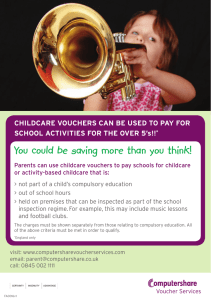

advertisement